NEWSLETTER | VOL. 9, JANUARY 2022

Welcome to this month’s edition of The Hollywood 360 Newsletter, your place to get all the news on upcoming shows, schedule and interesting facts from your H360 team!

Carl’s Corner

by Carl Amari

Hello everyone – here’s the Hollywood 360 Newsletter, January 2022 / Vol. 9. As someone on our mailing list, you’ll receive the most current newsletter via email on the first day of every month. If you don’t receive it by the end of the first day of the month, check your spam folder as they often end up there. If it is not in your regular email box or in your spam folder, contact me at carlpamari@gmail.com and I’ll forward you a copy. The monthly Hollywood 360 newsletter contains articles from my team and the full month’s detailed schedule of classic radio shows that we will be airing on Hollywood 360. Each month I’ll write an article on one of the classic radio shows we’ll present on Hollywood 360. The week of January 1st, 2022 we’ll be airing an episode of THE RED SKELTON SHOW so here’s an article on this comedy genius. Enjoy!

THE MANY CAREERS OF RED SKELTON

By Carl Amari and Martin Grams

Red Skelton’s brand of entertainment – top-notch, wholesome comedy and musical interludes — maintained a level of consistency that won him a devoted radio (and TV) following for decades. He was a light comedian with a background in burlesque and vaudeville, always ready to clown around and ridicule himself. Known for his sharp tongue and sassy jokes, Skelton was the consummate professional on air.

Red Skelton’s brand of entertainment – top-notch, wholesome comedy and musical interludes — maintained a level of consistency that won him a devoted radio (and TV) following for decades. He was a light comedian with a background in burlesque and vaudeville, always ready to clown around and ridicule himself. Known for his sharp tongue and sassy jokes, Skelton was the consummate professional on air.

Skelton made his radio debut in 1937 on Rudy Vallee’s The Fleishmann’s Yeast Hour and in 1938 replaced Red Foley as the host of Avalon Time on NBC. His wife Edna joined the cast under her maiden name; a talented writer, she finalized many of his bits. Two years later Skelton got his own radio show, The Raleigh Cigarette Program, in October 1941. The bandleader for the show was Ozzie Nelson, and his wife, Harriet, was the show’s vocalist and worked with Skelton in bits.

In addition to satirizing events in the newspaper headlines, Skelton performed routines regularly featuring characters such as “Junior, the mean widdle kid.” This naughty child contemplated the consequences of his bad behavior with the immortal catchphrase: “If I dood it, I get a whippin’ … but I dood it!” Many of the comedian’s stock characters, including singing cab driver Clem Kadiddlehopper; “Deadeye,” the fastest gun in the west; and “Willie Lump-Lump,” the loveable poet, soon found their way into listeners’ hearts. Skelton had an enormous file of gags that he consulted daily – but he often improvised, on the spot, to emphasize a joke.

As Skelton’s radio ratings soared, so did his celebrity status. During the notorious talent raids of 1949, CBS lured Skelton away from NBC in exchange for a large slice of financial pie. The move ensured Skelton’s transition to television, where he delighted a generation of baby boomers who had missed out on his radio comedy.

Although a big hit on radio, it was movies, television and his passion for painting clowns that brought Skelton his greatest success. Throughout the 1940s and 50’s, he starred in 19 films, including Ship Ahoy (1941), I Dood It (1943), Ziegfeld Follies (1946) and The Clown (1953). His television show premiered in 1951 and garnered huge ratings.

Throughout his life, he loved to paint clowns. Sales of his original oil paintings, prints and lithographs earned him millions per year in his later years. Shortly after his death in 1997, his art dealer said Skelton made more money on his paintings than from his television work.

LEND ME YOUR EARS | THIS MONTH’S SONG: HELPLESS (HAMILTON, MUSICAL BY LIN-MANUEL MIRANDA)

by Lisa Wolf

“In terms of musical theatre, it’s the opposite of what most people’s prejudices with musical theatre is: It’s not sunny and uplifting. I think that’s why it struck such a universal chord with people. This is not happy show tunes…It’s like a masterclass in how to use themes in order to take a short circuit to someone’s tear duct or heart or gut.” ~ Lin Manuel-Miranda

Hamilton tells the story of the nation’s Founding Fathers, including Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. Miranda wrote the music and lyrics and starred in the original production, which debuted on Broadway in 2015. The production garnered 11 Tony Awards, a Pulitzer Prize for drama and a Grammy for its original cast recording. As I have been fortunate enough to experience the Chicago production four times, I can assure you that it is nothing like any musical I had ever seen before. Hamilton is a high-energy show that tells Hamilton’s story using hip-hop, R&B and pop.

Lin-Manuel Miranda was on vacation in Mexico when he read Ron Chernow’s biography about Hamilton, and began to imagine it as a musical.

Originally planned for theatrical release on October 15, 2021, Hamilton was instead released worldwide to stream on Disney+ on July 3, 2020. It became one of the most-streamed films of 2020. The film was named as one of the best films of 2020 by the American Film Institute, and was nominated for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy and Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy (for Miranda) at the 78th Golden Globe Awards.

Originally planned for theatrical release on October 15, 2021, Hamilton was instead released worldwide to stream on Disney+ on July 3, 2020. It became one of the most-streamed films of 2020. The film was named as one of the best films of 2020 by the American Film Institute, and was nominated for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy and Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy (for Miranda) at the 78th Golden Globe Awards.

“Helpless” is the tenth song from Act 1 of the musical, and one of my favorites. The song focuses on the romance and eventual wedding of Eliza Schuyler and Alexander Hamilton. The original name for “Helpless” was “This One’s Mine”.

Vince’s Verbiage: The 1960s

by Carl’s Crabby Brother Vince

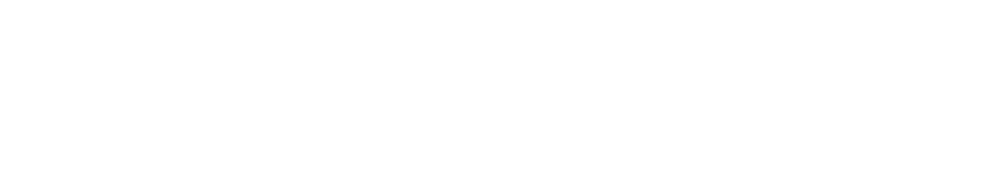

Let me start out by wishing all of our readers and their loved ones a Happy and Healthy New Year and many, many more. If you are a baby boomer like me and grew up in the Chicago area you might remember Riverview Amusement Park. It was located on 74 acres in the heart of the city at the corner of Western & Belmont Aves, an area the locals called Sharpshooters Park. It opened in 1904 with just a couple of rides and didn’t draw many visitors.

However, with an infusion of $550,000 in 1907 (a huge amount at the time) by a couple of investors, Riverview was able to add a few more rides. In 1909 they added a rollercoaster called The Derby which was incredibly popular right up to its destruction by fire in 1932. Four more coasters were built in the next few years. The Blue Streak in 1911 followed by The Gee Whiz in 1912, The Jack Rabbit Racing Coaster in 1914 and The Cannon Ball in 1919. The Roaring Twenties saw no less than five additional coasters built in the decade. The Big Dipper (AKA: Zephyr & The Comet) in 1920, The Pippen ( Later named The Silver Flash or Flash) in 1921, The Sky Rocket (AKA: Blue Streak & Fireball) in 1923, The Bobs in 1924 and then The Kiddie Bobs in 1926. The Bobs was probably the most famous roller coaster at Riverview over the years because of its sheer speed. The construction of new rides came to a screeching halt from the effects of the Great Depression in 1929.

In 1932 workers re-tarring a roof started a massive blaze that heavily damaged The Derby roller coaster and destroyed an attraction called Bug House Fun House which was soon replaced by a new fun house, The famous Aladdin’s Castle. They then purchased a used ride called The Flying Turns in 1934 and placed it where The Derby once sat. In 1936 they converted an old observation tower into a new ride called The Pair-O-Chutes. You could see this ride from miles away because of how high it was. The first time I ever went on this ride I thought I was going to meet my maker. I must have been maybe 10 or 11 years old, two people sit in a wooded seat as you slowly ascend skyward, then once you reach the top, a parachute opens and you not so slowly come back down to Earth. However, what I didn’t know that first time was when you reach the top it stops quickly and lifts you off your seat. I thought I was going to fall out of the chair!

In 1932 workers re-tarring a roof started a massive blaze that heavily damaged The Derby roller coaster and destroyed an attraction called Bug House Fun House which was soon replaced by a new fun house, The famous Aladdin’s Castle. They then purchased a used ride called The Flying Turns in 1934 and placed it where The Derby once sat. In 1936 they converted an old observation tower into a new ride called The Pair-O-Chutes. You could see this ride from miles away because of how high it was. The first time I ever went on this ride I thought I was going to meet my maker. I must have been maybe 10 or 11 years old, two people sit in a wooded seat as you slowly ascend skyward, then once you reach the top, a parachute opens and you not so slowly come back down to Earth. However, what I didn’t know that first time was when you reach the top it stops quickly and lifts you off your seat. I thought I was going to fall out of the chair!

In 1958 they added a ride called The Wild Mouse. This was a very unique roller coaster. It wasn’t fast, it didn’t have high scary drops or loops. You sat in a car that had a mouse head in the front. It had a turning mechanism attached to the track on the bottom in the MIDDLE of the car so when you reached a turn the front half of the car would keep going straight (you thought the car was going to plunge off the track into the river or to the ground) until the MIDDLE of the car reached the edge and would make a sharp turn. This was very scary for young kids. By the time I started going to Riverview in the late 1950’s they had many more rides and attractions like The Rotor. A couple dozen people would stand with their backs against a red padded wall in a round enclosure. Once everyone was in place, the ride would spin faster and faster until the floor drops out from under you and you’re plastered against the wall while the floor is about six feet below. A very cool ride. One of my favorite attractions was the freak show which featured the usual bearded lady and a mermaid half woman half fish. Also a man named Popeye, this guy would make his eyeballs pop half way out of their sockets. Hence the stage name Popeye. Another man would drive nails into his head and up his nose. He was billed as The Human Blockhead. But the roller coasters were the most fun.

I was lucky enough that my Uncle Philip for years worked for a construction company that built many of the rides and knew a lot of the people that worked there. A few times every summer he would come and pick up my two sisters and me (Carl wasn’t born yet) and would take us to Riverview. He would drive up to the ticket booth with us in the car and when they saw it was him they would always wave us in for free — EXCEPT for one time. This one time was not a good day for the gentleman that refused to let us in. Now my uncle Philip was only about 5’ 5” tall but he looked like a body builder and was as strong as a bull. He pulled the car over, got out and went inside the ticket shack. About 10 minutes later he came back to the car and somebody else proceeded to let us in. Needless to say the man that refused us entry never did that again.

To me Riverview had the most awesome rides, even better than Six Flags. Although maybe I feel that way because I was so young. Sadly, in October of 1967 it was announced that Riverview would not reopen ever again. Chicago was stunned and so was I. Now that I’m older I wish I could go back to those days for maybe just a week to enjoy Riverview one last time. We can dream can’t we?

Observations on the Obscure: MYSTERY IN THE AIR: Peter Lorre’s Psychopathic Studies in Horror

by Karl Schadow

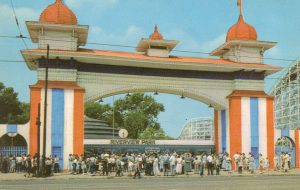

You have seen him in Fritz Lang’s M and also in The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca. On radio he served as host, introducing the weekly thrillers of the Armed Forces Radio Service Mystery Playhouse. Kate Smtih, Al Jolson and Ed Gardner invited him as a guest on their respective shows. Moreover, he made several appearances on such thrillers as Inner Sanctum and Suspense during the 1940s. It is a wonder that Peter Lorre did not rate his own radio series prior to the 1947 series Mystery in the Air. This article will provide a brief overview of the often-neglected horror program.

Mystery in the Air was not the first vehicle intended to star the native of Hungary. As early as 1943 Lorre was considered a possible candidate as The Whistler (Variety, May 12, 1943). The following year radio producer Norman Winter was promoting (via the 1944 Radio Daily Annual Shows of Tomorrow) Journeys Into Fear starring Peter Lorre in a half-hour suspense horror venue. Neither of these progressed past the audition phase.

Mystery in the Air was not the first vehicle intended to star the native of Hungary. As early as 1943 Lorre was considered a possible candidate as The Whistler (Variety, May 12, 1943). The following year radio producer Norman Winter was promoting (via the 1944 Radio Daily Annual Shows of Tomorrow) Journeys Into Fear starring Peter Lorre in a half-hour suspense horror venue. Neither of these progressed past the audition phase.

The June 9, 1947 issue of Broadcasting Telecasting stated that Wm Esty & Co., the advertising agency for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. (promoting its Camel cigarette brand) was slating Horror Stories as the summer replacement for the vacationing Bud Abbott & Lou Costello. The proposed venture would undergo a second name change to Horror in the Air before it was finally determined that Mystery in the Air would be acceptable to all parties. Perhaps the recent proclamation by NBC in toning down terror on network productions was the main factor in determining the moniker.

Commencing Thursday, July 3rd at 10 pm Eastern, listeners tuned in a chiller that was introduced by “The Voice of Mystery” Henry Morgan. The actor would later be known as Harry Morgan (of M*A*S*H and other television series). Stories chosen belonged to two literary camps with adaptations of 19th Century works of Edgar Allan Poe, and Alexander Pushkin intermixed with those of 20th Century masters W.W. Jacobs and Ben Hecht, among others. Lorre was a major factor in selecting the stories as Paul Luther noted in his syndicated newspaper column (July 9, 1947): “Few performers have a greater first-hand knowledge of the world’s literature than does Lorre – and he’s convinced that a deep appreciation and understanding of literature is absolutely necessary for any actor who really aspires to reach the top.”

Commencing Thursday, July 3rd at 10 pm Eastern, listeners tuned in a chiller that was introduced by “The Voice of Mystery” Henry Morgan. The actor would later be known as Harry Morgan (of M*A*S*H and other television series). Stories chosen belonged to two literary camps with adaptations of 19th Century works of Edgar Allan Poe, and Alexander Pushkin intermixed with those of 20th Century masters W.W. Jacobs and Ben Hecht, among others. Lorre was a major factor in selecting the stories as Paul Luther noted in his syndicated newspaper column (July 9, 1947): “Few performers have a greater first-hand knowledge of the world’s literature than does Lorre – and he’s convinced that a deep appreciation and understanding of literature is absolutely necessary for any actor who really aspires to reach the top.”

Frank Wilson of the ad agency adapted the first four scripts which included the opener, Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart. Not surprisingly, Lorre’s performance received high praise in Daily Variety, (July 7, 1947) which heralded: “For case-hardened mystery fans it was a field day for here were the Master Shockers of them all (that Welles’ Martian scare was sissy stuff) – Mr. Terror and Mr. Horror in person.” For the following twelve weeks, Lorre captivated not only listeners at home but also the audience which packed Studio A of the KFI-NBC Hollywood facilities.

Another interesting aspect of the series was that the orchestra, directed by Paul Baron was concealed behind two heaven curtains. Moreover, a rounded plexi-glass barrier was positioned on stage with Lorre and the cast working in front. These intricacies were promulgated by producer Don Bernard and director Calvin Kuhl. The all-important sound effects were performed by Floyd Caton. The studio booth engineer was John Pawlek. It is a credit to Lorre and the production staff that full casts were acknowledged at the end of each broadcast. Special recognition was bestowed upon Agnes Moorehead in “The Lodger” (August 14, 1947).

Unfortunately, there is no extant audio of any of the first five episodes of the series including that of the second installment, “Leiningen Versus the Ants.” It would be a fascinating study to compare Lorre’s performance with those of William Conrad on both Escape and Suspense. Moreover, the fifth chapter “Nobody Loves Me” was the second opportunity Lorre had to perform this script as his initial engagement was on Suspense (August 30, 1945). Another story that was produced first on Radio’s Outstanding Theater of Thrills was “Beyond Good and Evil.” Both series utilized the Douglas Whitney adaptation of the Ben Hecht yarn. Lorre’s interpretation of the role of the murderer – Philip Gentry – is comparable to that of Joseph Cotten’s in Suspense (November 11, 1945). Also of interest, is that a month prior to the broadcast on Mystery in the Air (August 28, 1947), a repeat rendition of the script starring Vincent Price was aired on Suspense (July 17, 1947).

Among the additional episodes of Mystery in the Air that are extant include the Guy de Maupassant classic “The Horla” and “Crime and Punishment” adapted by Tom McKnight from the Columbia picture based on the novel by Feodor Dostoivsky. The latter closed out the series on September 25, 1947.

Have questions regarding Mystery in the Air, contact the author at khschadow@gmail.com

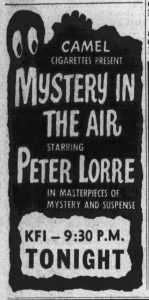

MartinGrams.biz: BING CROSBY, A MAN OF MANY TALENTS

by Martin Grams

For collectors of old-time radio, the common complaint is that many radio broadcasts were never recorded and therefore cannot be heard and enjoyed today. For historians who know better, we can thanks Bing Crosby for giving us so much to listen to. Radio broadcasts of the 1930s and 1940s aired live and was at that time considered a “throw away medium” — broadcast today, scripts were tossed into a box and hours later the script writer was hard at work on the next episode. No one thought about preserving the radio broadcasts via recording and since someone had to foot the bill, unless their was a practical reason the network and sponsor never took time to pay a company to record them. During the 1940s, as a result of a rising trend in technology, many of the top-rated radio personalities wanted to pre-record their radio broadcasts for convenience of a busy schedule. By 1945 there was high pressure and stormy implications brewing for the major networks and of all radio personalities, Bing Crosby was the big barometric push… the preamble of a condition long plaguing the big chains – that of playing a transcription disc across the nation through network feed.

For collectors of old-time radio, the common complaint is that many radio broadcasts were never recorded and therefore cannot be heard and enjoyed today. For historians who know better, we can thanks Bing Crosby for giving us so much to listen to. Radio broadcasts of the 1930s and 1940s aired live and was at that time considered a “throw away medium” — broadcast today, scripts were tossed into a box and hours later the script writer was hard at work on the next episode. No one thought about preserving the radio broadcasts via recording and since someone had to foot the bill, unless their was a practical reason the network and sponsor never took time to pay a company to record them. During the 1940s, as a result of a rising trend in technology, many of the top-rated radio personalities wanted to pre-record their radio broadcasts for convenience of a busy schedule. By 1945 there was high pressure and stormy implications brewing for the major networks and of all radio personalities, Bing Crosby was the big barometric push… the preamble of a condition long plaguing the big chains – that of playing a transcription disc across the nation through network feed.

In 1945, executives at the Mutual Broadcasting System publicly stated they were welcome to the proposal and insisted that within two years taping radio programs in advance would become the standard. ABC granted permission dependent on certain time slots. NBC and CBS, however, had strict policies avoiding the use of transcriptions. Top-rated radio performers longed to record their programs in advance, at a convenient time, rather than perform “live” to the masses… strongly campaigning for the privilege. And it was this fallacy that NBC was short-sighted… costing them a number of their top-rated comedians… including Jack Benny.

In 1945, executives at the Mutual Broadcasting System publicly stated they were welcome to the proposal and insisted that within two years taping radio programs in advance would become the standard. ABC granted permission dependent on certain time slots. NBC and CBS, however, had strict policies avoiding the use of transcriptions. Top-rated radio performers longed to record their programs in advance, at a convenient time, rather than perform “live” to the masses… strongly campaigning for the privilege. And it was this fallacy that NBC was short-sighted… costing them a number of their top-rated comedians… including Jack Benny.

It was in the summer of 1945 that relations between Bing Crosby and Kraft Foods was in a state of flux, with the strong possibility that the crooner would not return to the radio mike for the next season. Crosby’s contract with the J. Walter Thompson agency ran through 1946; his contract with Kraft had another five years to realize. When Crosby and his attorney met in Chicago with Willard F. Lochridge, vice president of Thompson, in August of 1945, the singer explained he received flattering offers from potential sponsors and Lochridge was instructed to inform executives at Kraft that he would remain with the cheese outfit only under the terms of a re-negotiated contract — which included recording the programs in advance. General Motors made a firm offer to sponsor Crosby, broadcast over the Mutual network, via wire recorder. That meant Crosby could make as many as eight or ten radio broadcasts in a single week, thereby allowing him the freedom he wanted for many weeks following. Crosby liked the idea so well he approached NBC with the option of recording the broadcasts in advance on platters. NBC gave a firm no.

It was in the summer of 1945 that relations between Bing Crosby and Kraft Foods was in a state of flux, with the strong possibility that the crooner would not return to the radio mike for the next season. Crosby’s contract with the J. Walter Thompson agency ran through 1946; his contract with Kraft had another five years to realize. When Crosby and his attorney met in Chicago with Willard F. Lochridge, vice president of Thompson, in August of 1945, the singer explained he received flattering offers from potential sponsors and Lochridge was instructed to inform executives at Kraft that he would remain with the cheese outfit only under the terms of a re-negotiated contract — which included recording the programs in advance. General Motors made a firm offer to sponsor Crosby, broadcast over the Mutual network, via wire recorder. That meant Crosby could make as many as eight or ten radio broadcasts in a single week, thereby allowing him the freedom he wanted for many weeks following. Crosby liked the idea so well he approached NBC with the option of recording the broadcasts in advance on platters. NBC gave a firm no.

The Kraft contract was unusual because it contained a “happiness” clause, which meant Crosby could not be forced to broadcast if he was unhappy about the terms of the contract. His financial advisors assured crooner that if he dropped off radio entirely, he would be losing only $1.50 a week, taxes being what they were. Crosby made his fortune through investments nevertheless his star status and draw appeal was an influence on his business ventures and staying in the radio spotlight was essential to long-term security.

The Kraft contract was unusual because it contained a “happiness” clause, which meant Crosby could not be forced to broadcast if he was unhappy about the terms of the contract. His financial advisors assured crooner that if he dropped off radio entirely, he would be losing only $1.50 a week, taxes being what they were. Crosby made his fortune through investments nevertheless his star status and draw appeal was an influence on his business ventures and staying in the radio spotlight was essential to long-term security.

In September, there was an attempt to arrive at an amicable agreement on disputed points in Crosby’s contract. Lawyers in Chicago grappled with the contract problem for a couple of weeks but long discussions ended in the decision to submit Kraft’s latest proposal to Crosby through the offices of the top two executives. Upon learning of the possibility that Crosby might drop Kraft, top radio bankrollers were ordering executives at New York ad agencies to “get Crosby or else.” Everett Crosby, Bing’s brother and agent, handled most of the negotiations, assuring Lochridge that other offers were on the table and some were appealing. Lochridge, when grilled by reporters, claimed “Bing is just tired and wants to take a long rest. There is no contract dispute and he is apparently contented with other phases of his association with Kraft and Thompson.” With five years on the contract, Kraft was unwilling to release Crosby for another sponsor.

“They know Bing’s weakness is canned broadcast so that he isn’t tied down every week and it’s on that promise from which the big pitch is being made,” Jack Hellman reported in Variety. “If it’s open season on Crosby, what’s to prevent Bob Hope, Jim and Marian Jordan, Jack Benny and a few other top-holers from becoming fair game?”

“They know Bing’s weakness is canned broadcast so that he isn’t tied down every week and it’s on that promise from which the big pitch is being made,” Jack Hellman reported in Variety. “If it’s open season on Crosby, what’s to prevent Bob Hope, Jim and Marian Jordan, Jack Benny and a few other top-holers from becoming fair game?”

Everett Crosby, meanwhile, asserted that the Kraft contract expired last July, under California law, which placed a seven-year limit on the term of any employment contract. The Thompson agency would not recognize the California law, insisting Crosby was tied to Kraft until 1950.

The stalemate lingered for months, with Kraft in early December making the following public statement, through the J. Walter Thompson Agency, which could be interpreted as a legal threat against any company seeking Crosby as a new client: “Bing Crosby’s sponsor is not trying to force [him] to return to the air, but is rumored to wonder how any other firm could contemplate having Bing for radio in view of his present long-term contract. Legal action is entirely possible under the contract which runs until 1950.”

The stalemate lingered for months, with Kraft in early December making the following public statement, through the J. Walter Thompson Agency, which could be interpreted as a legal threat against any company seeking Crosby as a new client: “Bing Crosby’s sponsor is not trying to force [him] to return to the air, but is rumored to wonder how any other firm could contemplate having Bing for radio in view of his present long-term contract. Legal action is entirely possible under the contract which runs until 1950.”

On January 3, 1946, the Kraft Food Co. filed a suit for declaratory judgment and injunction. On January 2, Crosby was asked to resume with Kraft Music Hall on January 3, the start of a new cycle, and when Crosby flatly refused, court action was initiated.

In a statement issued by Kraft: “The contract originated in 1937 provided for Bing’s radio services during that year with options to Kraft to renew the contract each year into 1950. We have exercised these options to date and have notified Bing of our exercise of the option for 1946. However, Bing claims that there is no longer any agreement enforceable against him, and Kraft has filed this suit in order that the court can determine whether these contracts are still binding and enforceable.”

On January 22, Bing Crosby and Kraft kissed and made up. Crosby would complete the season at the request of the sponsor. Kraft would then give him his release, satisfied with a moral victory.

In March, Procter & Gamble offered Crosby a transcription deal at $22,500 a week if he whipped out his fountain pen. The Mutual Broadcasting System had the firm offer typed on paper, ready and waiting. In May, ABC offered Crosby a stock deal, making him a partner in the network… also offering him a transcription deal.

In March, Procter & Gamble offered Crosby a transcription deal at $22,500 a week if he whipped out his fountain pen. The Mutual Broadcasting System had the firm offer typed on paper, ready and waiting. In May, ABC offered Crosby a stock deal, making him a partner in the network… also offering him a transcription deal.

Transcription business and recording studios were looking forward to halcyon days – and by many account they all depended on Bing Crosby. Where the crooner goes, thus goes the trade, was the belief. Crosby definitely wanted a platter program and he got it. On Thursday, August 15, 1946, Philco and Crosby signed a contract, closing the deal, which would send his voice over 600 stations weekly. The package price for the series was $30,000 a week, with the stipulation that in the event the Hooper rating fell below 12, the series would revert to live broadcasting. (Crosby would snare 24 on his premiere broadcast.) Philco originally wanted five seasons; Everett Crosby negotiated the compromise to a three-year contract. Crosby would get an additional $40,000 per week from 400 independent radio stations for the rights to broadcast the 30-minute show, which was sent to them on three 15-inch lacquer/aluminum discs that played ten minutes per side at 33 and 1/3 rpm.

In mid-October, network fears of the threat of transcribed shows were stressed when several gags about Bing Crosby’s transcribed show, which were to have been used on Rudy Vallee’s live layout for NBC on the evening of October 22, were blue-penciled by NBC brass shortly before the show went on the air. The network’s action brought cracks to the effect that “it’s about time” from trade columnists, who wondered what happened to NBC’s ban on cross references following jokes on the Jack Benny, Bob Hope and Ed Gardner programs also about Crosby being transcribed.

In mid-October, network fears of the threat of transcribed shows were stressed when several gags about Bing Crosby’s transcribed show, which were to have been used on Rudy Vallee’s live layout for NBC on the evening of October 22, were blue-penciled by NBC brass shortly before the show went on the air. The network’s action brought cracks to the effect that “it’s about time” from trade columnists, who wondered what happened to NBC’s ban on cross references following jokes on the Jack Benny, Bob Hope and Ed Gardner programs also about Crosby being transcribed.

Despite the ban on Crosby jokes on Rudy Vallee’s program, Bob Hope came through for his sidekick via ad-libs on his New York-originated show the same evening, also on NBC, in which he plugged Crosby in an exchange with guest Clifton Fadiman – to give further credence to the fact that the names were hot to follow Crosby’s lead in going plattered. Crosby, meanwhile, tucked six disc shows under his belt and went off on a hunting trip at his ranch in Elko, Nevada, with Jimmy Demaret and Ben Hogan, pro golfers. Crosby would not have had to make additional transcriptions for more than a month. Legend has it that Crosby wanted to record productions in advance so he could devote more time to golf. In reality, he visited a hospital twice during his strike with Kraft Foods as a result of exhaustion. Network executives couldn’t understand how it was so fatiguing to work seven days a week with writers conferences, rehearsals, agency executives and radio studios. Meanwhile, Benny, Hope and Gardner had to continue working week after week, live at the studios.

Two years after Crosby began transcribing his programs in advance, the June 9, 1948, issue of Variety reported that Bing Crosby “has disproved network arguments that transcriptions aren’t as good as live shows. Tape has in the past year completely altered not only the operation on top ABC shows, but has changed the thinking of the entire industry regarding recorded programs.”

Flash forward to 1948. Jack Benny and Amos and Andy made the switch to CBS. This was the start of what has become the notorious talent raids. Sure, CBS threw big money at the comedians and literally owned the actors who were forbidden henceforth to appear on NBC or ABC without permission — they practically became CBS property. But the deal breaker in those negotiations was not the cash aspect… it was permission to record the programs in advance in the same manner as Bing Crosby. According to one source, Jack Benny shook hands with William S. Paley and told him, “You have me.”

It wouldn’t be until February 3, 1949, that NBC made it official that taped or pre-recorded programs would be permitted on the network. By then, however, it was too late and NBC lost a dozen of their top rated radio personalities. The network’s long-standing policy against recorded programs was revived “as a further step towards promoting program flexibility and improving service to listeners,” quoted Ken Dyke, administrative vice president in charge of programs. The procedure would be followed only where talent, advertiser, agency and network agreed that the show would be improved by use of the transcriptions. Ampex tape machines were installed at NBC and it was theorized by many in the industry that most of the network programs would be transcribed before the season ended.* CBS would soon announce a similar policy on recordings since the acquisition of Bing Crosby, whose shows had been taped in advance on ABC, but this was a “public trade release” and CBS was already transcribing their programs for the benefit of their top-rated clients.

It wouldn’t be until February 3, 1949, that NBC made it official that taped or pre-recorded programs would be permitted on the network. By then, however, it was too late and NBC lost a dozen of their top rated radio personalities. The network’s long-standing policy against recorded programs was revived “as a further step towards promoting program flexibility and improving service to listeners,” quoted Ken Dyke, administrative vice president in charge of programs. The procedure would be followed only where talent, advertiser, agency and network agreed that the show would be improved by use of the transcriptions. Ampex tape machines were installed at NBC and it was theorized by many in the industry that most of the network programs would be transcribed before the season ended.* CBS would soon announce a similar policy on recordings since the acquisition of Bing Crosby, whose shows had been taped in advance on ABC, but this was a “public trade release” and CBS was already transcribing their programs for the benefit of their top-rated clients.

* Al Jolson got the first crack at tape-recording an NBC show, the first to get the Ampex treatment, for his March 10 broadcast of The Kraft Music Hall.

Crosby fulfilled this three-year commitment to Philco and ABC, accepting a lucrative offer with CBS under sponsorship with Chesterfield, beginning in September of 1949. Seeking better quality through recording, including being able to eliminate mistakes and control the timing of his show performances, the singer used the latest and best sound equipment and arranged the microphones his way; the logistics of microphone placement had been a debated issue in every recording studio since the beginning of the electrical era. Using his own Bing Crosby Enterprises to produce the show, the investment allowed Crosby to make even more money by finding a loophole whereby the IRS couldn’t tax him at a 77 percent rate.

The latest in technology, taping the broadcasts instead of transcribing them, allowed Crosby to do a 35 or 40-minute show, then edit it down to the 26 or 27 minutes required. Taking out jokes, gags or situations that didn’t play well, what remained was only the prime mat of the show; the solid stuff that played big. The second season of the Philco shows were taped with the new Ampex Model 200 tape recorder, using the new Scotch 111 tape from the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing (3M) company. Crosby’s investment was more prominent than critics could anticipate when the networks began adapting similar technology, becoming customers of an industry standard set by the singer.

On March 1, 1949, NBC executives at the “affiliate crisis meeting” in Chicago spotlighted attention on the just-released annual statement of the parent Radio Corp. of America, with its net annual earnings of $24,000,000, as evidence that it would take more than the loss of a few shows and personalities to put the network out of business. In effect, NBC’s argument was that “with $24,000,000 you can buy 12 Jack Bennys and 24 Bing Crosbys” (at the CBS rate of exchange).

On March 1, 1949, NBC executives at the “affiliate crisis meeting” in Chicago spotlighted attention on the just-released annual statement of the parent Radio Corp. of America, with its net annual earnings of $24,000,000, as evidence that it would take more than the loss of a few shows and personalities to put the network out of business. In effect, NBC’s argument was that “with $24,000,000 you can buy 12 Jack Bennys and 24 Bing Crosbys” (at the CBS rate of exchange).

In another effort to counter the talent raids, NBC developed moderately-budgeted programs. Hoping to avoid losses, the network retained either full or part control of the packages, avoiding advertising agencies, and sought commercial sponsorship themselves. Among the projected was the signing of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis to a weekly series, James Mason and his wife for a whodunit series (titled Illusion, a.k.a. The James and Pamela Mason Show), and a revival of Rogue’s Gallery with Dick Powell. (Powell would star in a detective program, Richard Diamond, Private Detective, after Rogue’s Gallery failed to be revived.) Proposals that never met fruition was a Kenny Delmar series based on the fictional character of Senator Claghorn, and radio serialization of The Man Who Came to Dinner. (The latter of which was revised as a weekly program with Monty Woolley titled The Magnificent Montague.

Less than nine months from Benny’s debut on CBS, Paley managed to lure other comedians from NBC to CBS: George Burns and Gracie Allen, Bing Crosby (both premiered on CBS on the evening of September 21, 1949), Edgar Bergen, Red Skelton (both October 2), and Horace Heidt (September 4). Bergen was a television enthusiast for years, understanding that his act worked best visually, and devoted considerable time during his temporary “retirement” to filming two television pilots, which he bankrolled himself. His television debut was on Thanksgiving 1950, weeks after he made his CBS radio debut. The pilot was produced by Bergen himself, of which 30,000 feet of film was shot – 27,000 feet ended up on the cutting room floor. Bergen understood the risks involved, having to compete against Paul Winchell who beat Bergen to the punch on television, and was willing to take a financial loss on the pilot in an effort to make a big impression with the network. (Footage that remained from the cutting room floor was later edited into a second proposed pilot. Coca Cola bankrolled part of the budget.)

During the summer of 1949, Paley was reported making overtures to Al Jolson into the Columbia fold. Paley was hot after the singer after the theatrical release of The Jolson Story (1946) but the singer was grabbed by Kraft and NBC. With a client interested, stemming from the anticipated success of Jolson’s new pic, Jolson Sings Again (1949), it was Paley’s hope to succeed where he lost two years prior. “Already raising its arm as the Champ of the Year in gross time sales, CBS has demonstrated how money and shrewd business acumen can parlay a network into No. 1 position,” wrote George Rosen in Variety. “NBC’s loss of major accounts and top stars to CBS is already reflected in the comparative billings – this year vs. last year – and in the amount of good time available and client who’s interested.” NBC continued to create in-house programs, co-owned by the network, including Dangerous Assignment, Dimension X and The Big Show — the latter of which (don’t let anyone tell you otherwise) was created solely to kill Jack Benny’s career for switching networks.

During the summer of 1949, Paley was reported making overtures to Al Jolson into the Columbia fold. Paley was hot after the singer after the theatrical release of The Jolson Story (1946) but the singer was grabbed by Kraft and NBC. With a client interested, stemming from the anticipated success of Jolson’s new pic, Jolson Sings Again (1949), it was Paley’s hope to succeed where he lost two years prior. “Already raising its arm as the Champ of the Year in gross time sales, CBS has demonstrated how money and shrewd business acumen can parlay a network into No. 1 position,” wrote George Rosen in Variety. “NBC’s loss of major accounts and top stars to CBS is already reflected in the comparative billings – this year vs. last year – and in the amount of good time available and client who’s interested.” NBC continued to create in-house programs, co-owned by the network, including Dangerous Assignment, Dimension X and The Big Show — the latter of which (don’t let anyone tell you otherwise) was created solely to kill Jack Benny’s career for switching networks.

Historians have been quick to point out the financials involved, but historical perspective verifies the true lure to CBS was the promise of transcribing broadcasts in advance – and NBC was temporarily shortsighted and stubborn to change their policy regarding pre-recorded radio broadcasts. NBC, however, was a fighting network and still determined to inch back into grandeur and stature, evident by lavish excursions into promotion and public relations, the earmarking of millions of dollars for new programs, proving that there would always be an NBC to reckon with. But that is another story for another time.

Hollywood 360 Schedule

1/1/22

The Red Skelton Show 12/31/48 New Year’s Show

Our Miss Brooks 12/31/50 Exchanging Presents

The Great Gildersleeve 12/31/44 New Year’s Eve

Hopalong Cassidy 1/1/50 Dead Man’s Hand

Danger, Dr. Danfield 12/15/46 Sam Hardy Makes a Bet With Death

1/8/22

Suspense 5/4/44 The Dark Tower

Broadway Is My Beat 5/5/51 Harry Foster Case

Escape 6/2/50 Mars Is Heaven

My Favorite Husband 12/9/50 Trying to Cash the Prize Check

The Shadow 3/13/38 The Silent Avenger

1/15/22

My Friend Irma 3/28/49 April’s Fool’s Party

Barrie Craig, Confidential Investigator 7/8/52 Long Way Home

Have Gun-Will Travel 6/21/59 North Folk

The Whistler 6/2/47 Caesar’s Wife

Night Beat 5/25/51 Fear

1/22/22

The Danny Kaye Show 2/17/45 Teaching Old Dogs New Tricks

The Chase 8/14/52 The Amusement Park

Dragnet 12/29/49 The Flowerland Roof Murder

The Weird Circle 8/12/43 Vendetta

Honest Harold 2/7/51 Harold’s Mother’s Suitor

1/29/22

The Adv. of Frank Race 5/1/49 The Adv. of the Hackensack Victory

Command Performance 5/18/42 w/ George Raft

The Jack Benny Program 10/20/46 Whistler Spoof

Richard Diamond, Private Detective 10/8/49 Gibson Murder Case

Under Arrest 8/21/49 Ruth Cutler’s Burglar

© 2021 Hollywood 360 Newsletter. The articles in the Hollywood 360 Newsletter are copyrighted and held by their respective authors.