NEWSLETTER | VOL. 12, April 2022

Welcome to this month’s edition of The Hollywood 360 Newsletter, your place to get all the news on upcoming shows, schedule and interesting facts from your H360 team!

Carl’s Corner

by Carl Amari

Hello everyone – here’s the Hollywood 360 Newsletter, April 2022 / Vol. 12. As someone on our mailing list, you’ll receive the most current newsletter via email on the first day of every month. If you don’t receive it by the end of the first day of the month, check your spam folder as they often end up there. If it is not in your regular email box or in your spam folder, contact me at carlpamari@gmail.com and I’ll forward you a copy. The monthly Hollywood 360 newsletter contains articles from my team and the full month’s detailed schedule of classic radio shows that we will be airing on Hollywood 360. Each month I’ll write an article on one of the classic radio shows we’ll present on Hollywood 360. The week of April 16th, 2022 we’ll be airing an episode of Bold Venture starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall so here’s an article on this Hollywood power couple and their exciting radio series. Enjoy!

Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall and Bold Venture

By Carl Amari and Martin Grams

One of Hollywood’s first power couples, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall displayed on-screen sexual chemistry in a total of four movies and were married in 1945. Networks regularly offered them their own weekly radio program and in 1951, they agreed to star in the radio adventure series Bold Venture, which was somewhat reminiscent of Key Largo (1948) their final film together. Made by their own production company, Bold Venture starred Bogart as Slate Shannon, the proprietor of a small, quasi-respectable hotel in Havana, inhabited by a motley, shifting cast of characters.

One of Hollywood’s first power couples, Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall displayed on-screen sexual chemistry in a total of four movies and were married in 1945. Networks regularly offered them their own weekly radio program and in 1951, they agreed to star in the radio adventure series Bold Venture, which was somewhat reminiscent of Key Largo (1948) their final film together. Made by their own production company, Bold Venture starred Bogart as Slate Shannon, the proprietor of a small, quasi-respectable hotel in Havana, inhabited by a motley, shifting cast of characters.

Instead of Sam, the pianist of Casablanca, the narrative featured a calypso singer named King Moses. Shannon’s motorboat, the Bold Venture, was on stand-by, ready to roar to the rescue of a friend or track down an enemy. Lauren Bacall played Sailor Duval, ostensibly Shannon’s ward and given a sultry edge by the glamorous actress.

With its exotic Cuban background and Latin-American flavor, the weekly seafaring adventure program was loaded with gun-fights, pirates, questionable characters, and romantic intrigue. Film buffs who enjoyed Key Largo welcomed another taste of Bogart and Bacall’s combined talents.

Never one to let work interfere with pleasure, Bogart had stubbornly rejected all offers for he and his wife to perform in a regular live radio series. But when radio syndicator, Frederic W. Ziv offered them a series of their choosing, recorded around their schedule, with a whopping budget of $12,000 per episode plus fees and royalties, the Bogarts couldn’t resist.

“I don’t want the usual detective story, with the typical detective and his husky-voiced blonde,” Bogart told scriptwriters Morton Fine and David Friedkin. “You know the type. There are at least ten or twelve on the air nightly, every week.” Attempting to follow the charismatic Bogart’s instructions, the scriptwriters came up with Bold Venture.

Bold Venture was produced by Bogart’s picture company, Santana Productions (named after a boat Bogart owned) and recorded in Ziv’s lavish Hollywood studio. The series premiered in the last week of March 1951 and was syndicated to 400+ radio stations. Almost 40 percent of the nationwide sponsorship came from breweries. The program was a tremendous success, earning the Bogarts more than $250,000 in just the first two years.

LEND ME YOUR EARS | DECEMBER, 1963 (OH, WHAT A NIGHT) BY THE FOUR SEASONS, RELEASED: 1975

by Lisa Wolf

“We figured we’ll come out of this with something. So we took the name of the bowling alley. It was called the Four Seasons.” ~ Bob Gaudio

In 1960, the group known as The Four Lovers evolved into The Four Seasons, with Frankie Valli as the lead singer. Members in the 1960s included Tommy Devito, Bob Gaudio, Nick Massi and Frankie Valli. The Four Seasons had a series of hits from 1962-1968. In 1975, they returned to the charts with “December 1963 (Oh What a Night),” which reached #3 in the U.S. The story of the song’s conception begins with songwriter Bob Gaudio, who initially wrote it as a celebration of the repeal of prohibition. Judy Parker (who later became Gaudio’s wife), suggested he rewrite it as a coming-of-age story in the form of a young man’s “first experience” – down to not even knowing the woman’s name, and the whole thing ending “much too soon”.

The story of the Four Seasons was dramatized in the Tony Award-winning Broadway musical Jersey Boys. The Four Seasons were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990.

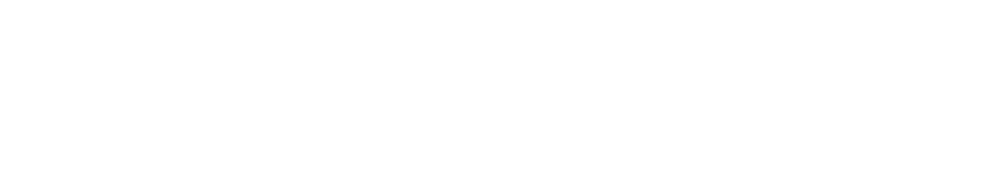

William Conrad – An Unconventional Hero

By Barry Richert

You know the voice as soon as you hear it; a rich baritone capable of asserting authority as Marshal Matt Dillon, grilling suspects as Detective Frank Cannon, or purveying puns as the narrator of the Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle. It belongs to William Conrad, a gifted actor who was able to have a successful career in radio, film, and television—some of it even behind the scenes.

William Conrad estimated he worked steadily as an actor on somewhere between 7,000 and 7,500 radio shows. His big network radio break was on the popular mystery series The Whistler. Conrad’s career snowballed from there, encompassing some of the most popular dramas on radio, including Escape, The Adventures of Sam Spade, Suspense, Lux Radio Theater, Fibber McGee and Molly, and the CBS Radio Workshop. Conrad was smart enough to simultaneously pursue a career in motion pictures, appearing in such films as The Killers; Body and Soul; Sorry, Wrong Number; East Side, West Side; and The Conqueror. Within a short span of time, Conrad had carved out a successful career in both radio and film. But the best was yet to come.

Radio producer Norman Macdonnell and writer John Meston were casting roles for a gritty new Western called Gunsmoke. Macdonnell wanted to avoid the stereotypical cowboy drawl in their lead character, Marshal Matt Dillon. After auditioning several actors, Macdonnell and Meston heard William Conrad. They both liked his reading enough to offer him the job, but network executives were hesitant. They wanted a big-name star to headline the show. With the deadline looming, Macdonnell threw caution to the wind and cast Conrad.

Radio producer Norman Macdonnell and writer John Meston were casting roles for a gritty new Western called Gunsmoke. Macdonnell wanted to avoid the stereotypical cowboy drawl in their lead character, Marshal Matt Dillon. After auditioning several actors, Macdonnell and Meston heard William Conrad. They both liked his reading enough to offer him the job, but network executives were hesitant. They wanted a big-name star to headline the show. With the deadline looming, Macdonnell threw caution to the wind and cast Conrad.

Gunsmoke debuted in April of 1952 and quickly became one of the most popular shows on radio, cementing Conrad’s status as the consummate radio actor. CBS was so pleased that they started to adapt the show for television. Unfortunately, the network didn’t want to use the radio cast for the TV series, and on a recommendation from John Wayne, James Arness was hired to play the television incarnation of Marshal Dillon.

Refusing to be discouraged, Conrad started taking a behind-the-scenes role in TV, producing first-run syndicated programs such as Highway Patrol and Bat Masterson. He also expanded his work as a voice actor by narrating the animated television series The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle for Jay Ward Productions.

After nine successful years, CBS informed Norman Macdonnell that it was time to get out of Dodge—the network was canceling the radio version of Gunsmoke. The final episode aired on June 18, 1961. Despite the popularity of Arness’ television portrayal of Matt Dillon, diehard fans of the radio series insisted nobody could play the role like Conrad. In the book “William Conrad, A Life & Career,” author Charles Tranberg provides a quote from Gunsmoke soundman Ray Kemper, who asserted, “Bill Conrad created the role of Matt Dillon, and in my opinion his interpretation of the U.S. Marshal was never matched.”

Conrad spent the rest of the 60s as a film and TV producer at Warner Brothers, but in 1970 he accepted an offer to star in Cannon, a detective series produced by the prolific Quinn Martin. Cannon was a portly former LA detective who enjoyed the finer things in life. Conrad admitted he wasn’t the conventional TV hero: “The whole concept of the leading man has changed. I think it’s wrong to bring up a generation believing that only beautiful people can do things.” The overweight, balding protagonist must have appealed to TV audiences; Cannon was a success from its first season.

The show made William Conrad a star and he became a favorite guest on variety series, anchored CBS’ coverage of the Thanksgiving Day Parade, and became the host of a wildlife program called Wild, Wild World of Animals. But in its fourth season, Cannon’s ratings took a significant tumble—from #10 to #21—and by the fifth season, the show disappeared completely from the top 30. CBS responded by canceling Cannon.

In the years that followed, William Conrad enjoyed the advantages of being an in-demand star and stayed busy as both a narrator and actor. When a 1980 TV movie called The Return of Frank Cannon failed to spark a revival, Conrad took another shot at series TV with Nero Wolfe. Based on mystery author Rex Stout’s successful series of novels, the show only lasted 14 episodes.

In 1987, William Conrad would star in his final TV series, Jake and the Fatman (spoiler alert: he didn’t play Jake). Developed by producer Dean Hargrove, the series was about J.L. McCabe, an L.A. District Attorney with a heart of gold and a penchant for profanity (his expletives were replaced with bleeps). The “Jake” in the title is Jake Styles, McCabe’s private investigator, played by Joe Penny. Jake was twenty-five years younger than McCabe and could handle all the physical tasks. This prevented the hefty Conrad from having to engage in any chase scenes or fisticuffs. By this time, Conrad was stipulating in his contract that he only work three days a week and have the freedom to leave for the day no later than five o’clock, which he always did…even if he was in the middle of shooting a scene.

Jake and the Fatman was a solid performer for CBS but was never a smash hit. After the fifth season, the network opted to cancel the series. William Conrad’s health may have played a part in the cancellation. “He was hypoglycemic and depending on what he ate his energy could fluctuate,” actor Alan Campbell, who played Assistant District Attorney Derek Mitchell, remembers. The last episode aired on September 12, 1992.

Conrad rarely worked after Jake and the Fatman. A year-and-a-half after its cancellation, on February 11, 1994, he was rushed to the North Hollywood Medical Center in cardiac arrest. Within minutes of arriving, Conrad was pronounced dead.

At one point in his career, an interviewer asked Conrad why he had achieved so much success in radio. His response included an expletive that would have amused the verbally indelicate J.L. McCabe: “There was always a danger thing in my voice. Now, I don’t know how that got there, but I covered everything with a black drape. I never took a drama lesson in my life. I never even thought about what it is to be an actor…I was just [bleep]ing lucky to have a voice that fascinated people.”

In 1997, three years after his death, William Conrad was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame.

MartinGrams.biz: KING KONG: PEOPLE WENT APE FOR HIM ON RADIO TOO!

by Martin Grams

“And the prophet said: And lo, the beast looked upon the face of beauty. And it stayed its hand from killing. And from that day, it was as one dead.” – Old Arabian Proverb

Bruce Cabot, Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong

Months before the motion-picture King Kong was released theatrically, a novelization of the screenplay appeared in print in 1932, adapted by Delos W. Lovelace, a friend of movie producer Merian C. Cooper and a minor writer who mainly scripted biographies and children’s books. Originally published by Grosset & Dunlap, the story was also serialized in two parts in 1932 by Walter Ripperger for Mystery magazine. Lovelace’s prose is by no means great, but the novel features descriptions of scenes not present in the motion-picture, including the legendary spider pit sequence.

Publication of the novelization was not the only means the studio used to promote the picture. Executives at RKO Pictures began making plans to promote their big screen epic, King Kong, supposedly a loose inspiration of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912). Advertising for the motion-picture was both elaborate and costly. The studio, without utilizing the practice of an advertising agency, purchased airtime in the space of fifteen-minutes, twice a week, Saturday and Monday. Incorrectly reported on a number of websites as a 30-minute weekly feature, the radio serial was considered a Holy Grail among connoisseurs of vintage radio broadcasts and fans of retro horror movies.

Fay Wray in a publicity photo

King Kong masquerades as a beauty and the beast fairy tale, a story involving a Hollywood producer who sought the eighth wonder of the world, only to partake in an adventure that takes him to an unchartered island and rampage through the streets of New York. The female protagonist named Ann Darrow, played by actress Fay Wray, found herself kidnapped by the giant gorilla named Kong, worshipped by the tribal natives, on an island occupied by prehistoric beasts. Sailors race across unexplored territory in an attempt to rescue the damsel, only to face gruesome death from all shapes and sizes. She was eventually rescued and in the process, Kong was knocked unconscious and brought back to New York City, where the beast was put on exhibition. Kong ultimately broke free of his bonds and ran amok through an asphalt jungle, destroying cars and climbing tall buildings. The monster met his demise in a historic cinematic sequence on top of the Empire State Building. But don’t kid yourself – theater goers in 1933 knew it was not a real ape. They observed the same stop-motion effects you see today.

As Joe Bigelow of Variety reported in his March 6, 1933 column, “It takes a couple of reels for King Kong to be believed, and until then it doesn’t grip. But after the audience becomes used to the machine-like movements and other mechanical flaws in the gigantic animals on view, and become accustomed to the phony atmosphere, they may commence to feel the power. As the story background is constantly implausible, the mechanical end must fight its own battle for audience confidence. Once won, it reaches a high pitch of excitement and builds up to a thrill finish in which the ape almost wrecks little ol’ New York.”

The March 3, 1933, issue of the New York Times remarked, “While not believing it, audiences will wonder how it’s done. If they wonder they’ll talk, and that talk plus the curiosity the advertising should incite ought to draw business all over. King Kong mystifies as well as it horrifies, and may open up a new medium for scaring babies via the screen.”

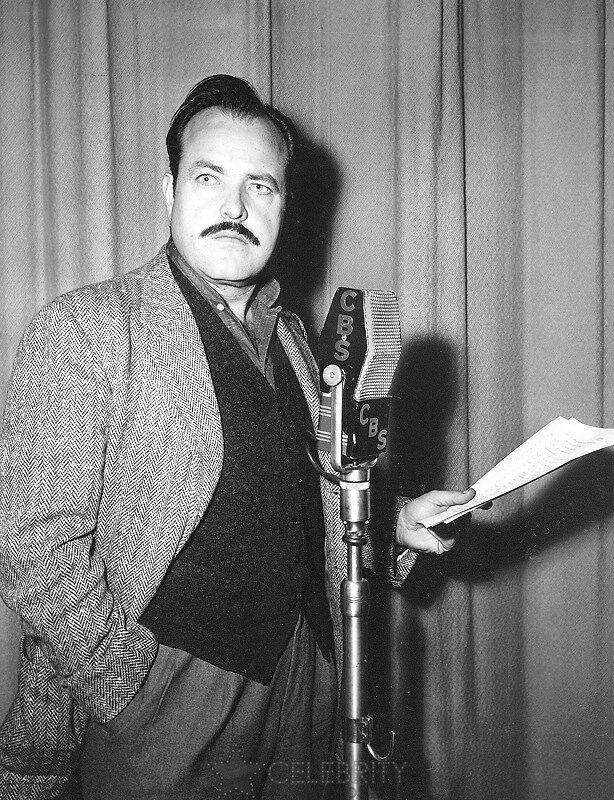

Merian C. Cooper

King Kong was the brainchild of Merian C. Cooper. To go into detail regarding the movie’s production would take multiple blog entries and we don’t have time for that. You can find a nice write-up about the production of the movie here:

RKO reportedly spent more than half a million to produce the movie so it comes as no surprise that the studio that was among the first to utilize the medium of radio as a means of publicizing their motion-pictures, decided to expand promotion of King Kong beyond commercial copy.

RKO predicted box office revenue surpassing most of their productions that calendar year and went to a lot of trouble to build publicity. They were correct as a number of inter-office memos suggest the studio would have filed bankrupt had King Kong not grossed as well as it did. The financial success of the movie, in part, is due to the major publicity – including using radio as an advertising medium. Publicizing on radio, however, was an unusual decision at the time – a medium shunned by movie studios in fear theater goers would abandon the silver screen for economical and convenient means of entertainment. Executives at RKO knew radio could help publicize their screen ventures and booked eight weeks on NBC to dramatize a fifteen-chapter radio serial adapted from the screenplay.

Like the movie put before the cameras, the struggle for survival on the primitive, fog-enshrouded, tropical Skull Island between the energetic filmmakers (led by Robert Armstrong), the hero (Bruce Cabot), and the forces of nature are dramatized. Unrequited love and the repression of violent sexual desires, a combat against the voodoo natives, and a depiction of economic oppression, was not evident upon reviewing the surviving radio scripts from the 1933 radio serial.

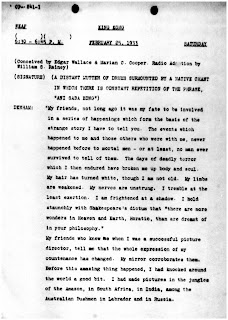

1933 King Kong radio script

Until recently, the radio serial, produced from March 18 to April 22, was considered “lost.” Among the Holy Grails of vintage radio broadcasts, no recordings were known to exist, produced from air checks. An LP record, produced many years later, has often been distributed over the Internet and mistakenly labeled as a chapter from the 1933 radio serial. To date, recordings of the 1933 broadcasts still do not exist. Few would not even know of its existence if it was not for a brief mention in the RKO press book for King Kong, and a number of newspaper listings. A collector residing in Virginia, however, who buys and sells radio scripts on eBay, apparently had in his possession originals of all 15 radio scripts – safely protected in a cardboard box –this discovery a historic find indeed.

From careful examination of the scripts, it is learned that New York stage actors played the roles. None of the Hollywood elite reprised their screen performances. The serial was originally slated for 16 broadcasts, twice a week, and while newspaper listings confirm this, further digging proved that a major news item (coverage of a major earthquake in Los Angeles) pre-empted one of the broadcasts. This forced the script-writer to combine two chapters into one.

The adaptation was handled by William S. Rainey, who was hired to adapt the screenplay and/or novelization into 16 chapters, each running 15 minutes in length. For the most part, Rainey remained faithful to the material. Rainey also doubled as the narrator for the opening and closing of every radio broadcast, and on occasion supplied voices of natives, sailors and spectators when action called for it. It was not uncommon during the thirties for radio actors, writers, directors and sound men to double for roles before the days of unions and guilds. Alois Havrilla, the director of the serial, was an accomplished radio announcer in his own right and it appears he also doubled for roles of natives, sailors and spectators. It seems more logical that Havrilla would have served as announcer while Rainey handled the directing – the names on the extant radio scripts were penciled in and the positions could have been mislabeled. Havrilla would venture to Hollywood shortly after completion of this radio play, signing a contract with Universal Studios for a series of film shorts. While on the West Coast, he would further his career as a radio announcer for Jack Benny’s The Chevrolet Program, Joe Cook’s Colgate House Party and Paul Whiteman’s Musical Varieties.

Merian C. Cooper and Fay Wray

There was no apparent opening theme for the chapter plays. The opening signature for each broadcast was the distant mutter of drums surmounted by a native chant in which there is constant repetition of the phrase, “Ani Saba Kong.” If anything, a few bars of “Oriental Love Dance” by Irénée Bergé would have been used, according to a single music cue sheet that survives from the NBC files. Other music featured on the program included “Queen of the Night” (from In Babylon) by Justin Elie, “In a Pagoda” by John W. Bratton, “Chinese Dance” (from Two Oriental Dances) by Bainbridge Crist, and parts one and eleven of “Sea Shantiss” arranged by Sir Richard Runcian Terry. Musical instruments included oboe, drums and accordion.

The opening chapter features Carl Denham, in the role of a Hollywood motion-picture director, related the events as it happened to the radio audience. Because the radio cast had not yet seen the motion-picture, they were instructed by the director not to view the film until after the conclusion of the radio serial, to ensure the personas depicted on celluloid would not influence the manner of which they portrayed the radio counterpart.

Stage and radio actor George Gaul, playing the lead of Carl Denham (referred to as Worthington Denham in the premiere episode and Carl throughout the remainder of the serial), played the part ala Richard Halliburton, a then-famous adventurer and lecturer. Halliburton’s first book, The Royal Road to Romance (1925), was a best seller. New Worlds to Conquer (1929) recounted his famous swim of the Panama Canal, retracing the track of Cortez’ conquest of Mexico, and a trip to Devil’s Island. Halliburton appeared on radio numerous times for the lecture circuit, recounting bizzare foreign encounters, often drawn from his real-life escapades. It is believed that Gaul played the role in the same manner as the eccentric Halliburton portrayed over the ether waves, complete with high-pitched voice and occasional discomfort on the details. Halliburton’s love of the world’s natural wonders, monuments bestowed to mankind from Mother Earth, may have partially been the inspiration for the character created for the motion-picture.

As the first chapter opens, Denham briefly introduces his background and foreshadows the aftermath of the horrific events. “My friends, not long ago it was my fate to be involved in a series of happenings which form the basis of the strange story I have to tell you. The events which happened to me and those others who were with me, never happened before to mortal men – or at least, no man ever survived to tell of them. The days of deadly terror which I then endured have broken me up body and soul. My hair has turned white, though I am not old. My limbs are weakened. My nerves are unstrung. I tremble at the least exertion. I am frightened at a shadow. I hold by stanchly with Shakespeare’s dictum that “there are more wonders in Heaven and Earth, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” My friend who knew me when I was a successful picture director tell me that the whole expression of my countenance has changed. My mirror corroborates them. Before this amazing thing happened, I had knocked around the world a good bit. I had made pictures in the jungles of the Amazon, in South Africa, in India, among the Australian Bushmen in Labrador and in Russia.”

The character of Denham provides first person narrative throughout most of the serial, bridged between extended action scenes which are almost verbatim from the film script.

Among the notable differences between the film script and the radio drama was the inclusion of the famous Spider Pit sequence, which was apparently cut from the film before the motion-picture was released nationally. (More about this next week on the blog.)

Other noticeable differences between the finished movie and the radio script was the way in which the old chief and witch doctor carried out their threats to offer Ann as a golden-haired bride for Kong. On the island, ceremonial fires were lit and Ann was covered with garlands. Her arms tied between two pillars, she witnessed first hand the roaring defiance of Kong. The scene in which the gates opened and Kong entered the village to take Ann away, followed by the natives’ closing of the gate, was not exactly the same manner depicted in the movie. Kong is apparently allowed to enter and exit with his sacrifice. The fact that the actress was not in the radio script may have had a hand in the formation of this scene.

Fay Wray

The initial length of King Kong was originally 14 reels but, to cut down on budget, the studio asked Cooper to trim the movie to 11 reels. Scenes that supposedly ended up on the cutting room floor was Kong’s confrontation with a Triceratops, Jack and Ann’s perilous escape down the river, and Kong crashing down Skull Mountain chasing after Jack and Ann. The fight between Kong and the Triceratops was featured in chapter nine, as evident in the script reprint.

In chapter eleven, Denham describes his trek back to the vessel for more guns and bombs, and his observations of the quietness of the native village. When Kong approaches in chapter thirteen, chasing Driscoll and Ann, the great ape smashes the gate and tears through the village. As Denham narrated, “Kong filled the aperture, his body in a crowd, his eyes peering above the little men at his feet to the dark huts. I gazed unbelievingly at the bulk of the invader and raced back for the gas bombs. Kong lumbered forward to begin a slow patient search of the still, dark village. In the cluster of huts the rays of the early dawn had not yet penetrated. The last native had fled to the deceptive shelter of his home or out into the encircling brush. Kong ripped off the top of one hut after another, stooping down to peer into each. At first, he only rumbles an impatient disappointment but as he met repeated failure his tune sharpened to fury. By a wide, swinging run behind concealing huts and trees, I finally interposed myself across Kong’s line of advance. Gripping a prized bomb in either hand, I kept my distance watchfully.”

In two radio episodes, the refuge is referred to as Skull Mountain Island. (Same for the Lovelace novel.) In the movie, it is referred to as Skull Mountain. It was mentioned in one chapter that Skull Mountain was located somewhere off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. RKO referred to it as Skull Island in publicity materials. (In Song of Kong, the 1933 motion-picture sequel, it is referred to as Kong’s Island.)

In the final episode, the scene where Kong reached in and takes Ann from her hotel room is not prominently referenced. Instead, Driscoll informs Denham in the streets that Kong kidnapped his prey and is climbing the buildings of the city. It is Driscoll who tells a police officer that army planes from Roosevelt Field “might find a way to finish Kong off.” Denham and Driscoll describe the confrontation to each other, between Kong and the planes as they witness the events from the street. (This was, no doubt, a cheat for sound effects men to avoid re-creating the sound of Curtiss Helldiver aircraft.) The death of Kong was described by Denham to the radio audience. It appears, based on analyzing the radio scripts, that the final two chapters were edited together as one. This might be why Kong’s escapades through the city and the daring rescue of Ann was provided mostly through narration and little action and sound effects.

Alois Havrilla

Beginning with the second episode, the following announcement was delivered over the radio by announcer George Hicks, over WEAF in New York only: “Our listeners in the vicinity of New York City may be glad to know that King Kong is of such tremendous interest that it will be presented at the Radio City Music Hall beginning Thursday, March 2nd, and at the new RKO-Roxy Theatre beginning Friday, March 3rd, for one week.” A similar announcement was repeated through chapter six. In other areas of the country, New Jersey, Connecticut and upstate New York, a station identification was instead provided. The cliffhanger serial was not heard in other areas of the country, including Washington, D.C., Chicago or Los Angeles.

EPISODE GUIDE

Broadcast Saturday and Monday, 6:30 to 6:45 p.m.

Originated from WEAF in New York City.

Episode #1, Broadcast Saturday, February 25, 1933

CAST: Pierce Benton (Bjorusen), Arthur Ebony (the watchman), Parker Fennelly, (Capt. Englehorn), George Gaul (Carl Denham), Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll), and Charles Webster (Weston).

PLOT: We are introduced to Worthington Denham, the famous picture director, whose adventure pictures, made in the far corners of the earth, have been seen by millions of people. Denham describes, through dramatic flashback, hearing by chance of a mysterious island in an uncharted portion of the Southern ocean, decided to try to find it and make a picture there. His previous pictures had been less successful than they should have been because they lacked romance. He decided to talk to a Norwegian skipper, Bjorusen, who in Singapore two years ago gave him the details of the mysterious island. Denham bought a boat, hired a skipper, Englehorn and his mate, Driscoll, who had been with him on two earlier voyages. Denham explains the reason why he needs to hire a young girl for the trip and sets out to find one.

Episode #2, Broadcast Monday, February 27, 1933

CAST: Peggy Allenby (Ann Darrow), George Gaul (Carl Denham), Joseph Granby (the fruit vendor), and William S. Rainey (the cabman and the narrator).

PLOT: The day before they were to set sail, the New York theatrical agents failed to find a girl willing to go on such a hazardous and mysterious voyage. Denham set out into the obscuring twilight of a snowy winter’s evening to hunt for her along the highways and byways of New York City. Saving a young starving beauty from arrest as a result of stealing an apple from a fruit peddler, Denham meets Ann Darrow and treats her to a full meal in a tiled lunchroom. She was undernourished but he promised to make good on full meals in the future… provided she tag along on his expedition.

Deleted Scene

DENHAM: How come you’re in this fix?

ANN: Bad luck, I guess. There are lost of girls just like me.

DENHAM: Not such a lot who’ve got your looks.

ANN: Oh, I can get by in good clothes, perhaps. But when a girl gets too shabby…

Episode #3, Broadcast Saturday, March 4, 1933

CAST: Peg Allenby (Ann Darrow), Parker Fennelly (Capt. Englehorn), Tim Daniel Frawley (Lumpy), George Gaul (Carl Denham), William S. Rainey (narrator), and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll).

PLOT: Boarding The Wanderer, Ann meets the first mate, Driscoll, who confesses his dislike towards having a woman on board, believing them to be “cock-eyed pests.” When the vessel gets west of Sumatra, Denham provides the map leading to Skull Island. Pictured on the map is a wall higher than a dozen men, and impregnable, stretching across the base of the peninsula serving as a mighty barrier against who or what might attempt to come down the precipice from the back country. Built so long ago that the descendants of the builders slipped back into savagery. Denham assures the men that the map is legit and that “every legend has a basis of truth.”

Episode #4, Broadcast Monday, March 6, 1933

CAST: Peg Allenby (Ann Darrow), Parker Fennelly (Capt. Englehorn), Tim Daniel Frawley (Lumpy), George Gaul (Carl Denham), William S. Rainey (narrator), and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll).

PLOT: With a strange mountain suggesting a skull, the crew is apprehensive in their journey. Ann, however, enjoys being on the ocean and longs to remain on the waters with each passing day. Denham asks Ann to pick something from the costume boxes that pleased her fancy, for camera tests. She had selected a curious primitive costume blend of soft, rustling grasses and softer, iridescent silken strips. Where it failed to cover her, the flesh of her arms and legs flashed in ivory contrast to the brown of the grasses and the brightness of the cloth. Denham refers to it as his “Beauty and the Beast” costume. After a screen test involving Ann screaming for her life, Driscoll expresses displeasure in the treatment she may be subjected to, confesses his love and the two romantically kiss. On the morning of May the seventh, they woke to find themselves in the midst of a thick yellow-white blanket of fog. They found the island as described on the map.

The Saturday, March 11, 1933 broadcast was not dramatized because of news coverage of Los Angeles earthquake coverage.

Episode #5, Broadcast Monday, March 13, 1933

CAST: Peg Allenby (Ann Darrow), Paul Durant (the Native Chief), Parker Fennelly (Capt. Englehorn), Tim Daniel Frawley (Lumpy), George Gaul (Carl Denham), Alois Havrilla (native voices), William S. Rainey (narrator), and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll).

PLOT: Arriving on the island, the adventurers find the natives performing some type of ceremony. Along for the trek are Driscoll, Ann, Denham, Engelhorn and about 40 members of the crew. The men observed the great wall first hand, observing a gate hinged to massive stone pillars supporting the story of the structure’s antiquity. There was also an overhanging precipice made chiefly of huge logs. The natives are chanting “Kong! Kong!” while a native girl, young and smoothly attractive, wearing an apparel consisting of woven strands of flowers, is offered as a sacrifice. The natives, discovering they have visitors, temporarily halt the proceedings. Engelhorn, able to speak the native language, discovers the girl is the bride and gift of Kong. Blondes are scarce in this part of the world and Ann, is eyed by the natives as a gift for Kong.

Episode #6, Broadcast Saturday, March 18, 1933

CAST: Peg Allenby (Ann Darrow), Paul Durant (the Chief), Parker Fennelly (Capt. Englehorn), Tim Daniel Frawley (Lumpy), George Gaul (Carl Denham), Alois Havrilla (native voices), William Naughton (the guard), William S. Rainey (narrator), and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll).

PLOT: The Chief of the natives offers six women for Ann, but the offer is declined and the men of The Wanderer retreat back to the vessel. Hours later, the men gather in the skipper’s cabin. Their first reaction had been one of exhilaration over the lucky outcome of their encounter. How, however, they had time to ponder the danger they had run – and the ominous mystery of the native chiefs’ parting words. Meanwhile, Lumpy shows the men a native bracelet found on deck… and Ann is missing. There was no doubt that the natives had been on the ship under the cover of darkness and spirited Ann away to a possible fate. A rescue party is formed.

Episode #7, Broadcast Monday, March 20, 1933

CAST: Parker Fennelly (Capt. Englehorn), George Gaul (Carl Denham), Taylor Graves (Jimmy and voice of sailor), Alois Havrilla (voices of sailors) and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll).

PLOT: The old chief and witch doctor carried out their threats to offer Ann as a golden-haired bride for Kong. The skipper ordered the boats manned. Every man was armed with a rifle and one of the boats contains a crate of gas bombs. On the island, ceremonial fires were lit and Ann was covered with garlands. Her arms tied between two pillars, she witnesses first hand the roaring defiance of King Kong. The beast takes Ann away and the natives close the gate. With Driscoll in the lead the men plunged into the murky jungle. The great size of the horrible monster awed all of them. Trekking through the jungle, the men risk arm and limb to track Kong. They encounter an immense beast with a thick, scaly hide, a huge spiked tail and a small reptilian head. They came face to face with surviving creatures of prehistoric life. Using the gas bombs, the men knock the creature out. But valuable time was being lost while Kong had Ann in his possession.

Episode #8, Broadcast Saturday, March 25, 1933

CAST: George Gaul (Carl Denham), Taylor Graves (Jimmy and voice of sailor), Alois Havrilla (voices of sailors), Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll and voice of sailor).

PLOT: Using logs the men venture downstream in speed of pursuit. The men continue to encounter monstrous apparitions, dinosaurs on water-soaked logs, and one scaly-back smashed the raft into pieces… sending the men into the water and guns to the bottom of the water. Denham felt sick wondering how many of the crew were to go before they could catch up with Kong. The men reach land and continue their trek, a tricerotop gores to death one of the rescue party, then ultimately witness Kong battling a Tricerotops. The battle, as described by Denham during the audible roars from the fight, reveal Kong the defiant. The chances of rescuing Ann from the fiendish clutches of Kong seem fainter and fainter.

Episode #9, Broadcast Monday, March 27, 1933

CAST: George Gaul (Carl Denham), Taylor Graves (Jimmy and voice of sailor), ALois Havrilla (voice of sailors), and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll).

PLOT: Of what use was the guile and wit against the huge fantastic beasts of the nightmare island? Their frail knives were useless and they lost their rifles and gas bombs when the raft was destroyed. Driscoll and Denham did their best to pull the men out of the mood of surrender. Driscoll agrees to cross the ravine and find Ann while the rest of the men return to the ship to fetch more rifles and bombs. The men ultimately plunge to their deaths in a pit of giant insects and spiders. Driscoll takes shelter in a cave in the ravine as Kong reaches in to apprehend his next prey. Driscoll, backing up, drew his knife and stabbed Kong’s fingers and arm, enraging the ape. Driscoll crouched in his shallow wall stabbing hopelessly at every chance…

Episode #10, Broadcast Saturday, April 1, 1933

CAST: George Gaul (Carl Denham), and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll).

PLOT: A giant snake made for Ann, who screamed for her life. Kong whirled about and Kong was again defiant. Driscoll, during the battle, snuck out of the cave and continued to following Kong to his lair. Ann’s one chance for continued safety depended upon his own ability to keep track of her and Kong’s temper. He trailed the ape, not provoking him to a furious outburst. Denham, who was witness to all that happened, agreed to go back to the boat and get bombs. Together the men cannot catch Kong. They need bombs to do that. Denham departs.

Episode #11, Broadcast Monday, April 3, 1933

CAST: Parker Fennelly (Capt. Englehorn), Tim Daniel Frawley (Lumpy), George Gaul (Carl Denham), and Alois Havrilla (voice of sailor).

PLOT: Meeting Capt. Englehorn in the village with the other men, Denham reveals that everyone was wiped out, except Driscoll and possibly Ann. He asks for volunteers to go back after them. Sleep was out of the question, tired as he was. The sailors completed preparations for a new search, armed with rifles and more bombs. The image of the sailors who met their fate was fresh on his mind. He feared the possibility of a similar fate for these men, and Driscoll was now sick at heart and with heavy misgivings, he could not free his mind of the disturbing thought that in a sense he was to blame for the whole horrible business. He cursed the day he ever heard of the island.

Episode #12, Broadcast Saturday, April 8, 1933

CAST: Peggy Allenby (Ann Darrow), George Gaul (Carl Denham), Alois Havrilla (voice of sailor), and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll).

PLOT: As described by Jack Driscoll, the first mate gave chase as the ape lumbered through the jungle. He was following no beaten trail, leaving his geat tracks plainly upon bruised leaves and broken branches and sodden jungle floor. Ann was, apparently, unconscious by this time. She lay in the crook of one of the beast’s enormous arms. Her hair foamed down her back in a bright cascade made more bright by its contrast with Kong’s black snarl of fur. Along the slope of the island’s highest peak, Kong came to a full stop in a great, natural amphitheatre which was encircled by a curving cliff. When a great bird-like monster, a prehistoric pterodactyl soared, Ann woke and screamed and Kong came to her rescue. During the fight, Driscoll made a move to rescue Ann. Together, the two jump off the ledge into the pool below. The two follow the stream to safety. They finally reach the gates of the great wall. But they are not yet beyond the gate and the crashing which they heard in the forest behind them was Kong in pursuit.

Trivia: Narration by Jack Driscoll, filling in on the events on the island, after Denham introduces him to the audience.

Episode #13, Broadcast Monday, April 10, 1933

CAST: Peggy Allenby (Ann Darrow), Parker Fennelly (Capt. Englehorn), George Gaul (Carl Denham), and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll).

PLOT: Denham and his men reached the gate about the same time as Ann and Driscoll. Racing back to the Plain of the Altar, everyone was delirious with joy. Before the men agree to leave the island, Denham points out that he was here to make a moving picture and Kong was worth all the movies in the world. They have bombs and if they capture him alive, they will have proof of their story for all the world to see. Against the wishes of Ann and Driscoll, Denham wants to use the beauty as bait. Before the great doors can close completely, Kong’s lumbering bulk rolls against the wall, shouting a wail of terror. The gap at the gate had become scarcely more than a wide crack when Kong’s charge struck home. The surprised natives scream and flee in terror. The gate fell inward with a terrific crash. Sailors scramble shrewdly to safety on either side. Kong tears through the village and Denham throws a bomb squarely against Kong’s chest so that the liquid struggled blindly on, knocking the beast out. With the giant beast conquered, Kong is put into chains and arrangements made to transport him back to New York. After considerable effort the men got the animal towed out to the ship, as she lay at anchor in the little harbor. “We’ve got the biggest capture in the world,” Denham tells the skipper. “There’s a million in it. And I’m going to share it with all of you. Listen! A few months from now it’ll be up in lights on Broadway. The spectacle nobody will miss. King Kong! The Eighth Wonder of the World!”

Episode #14, Broadcast Saturday, April 15, 1933

CAST: Peggy Allenby (Ann Darrow), George Gaul (Carl Denham and voice three), Jack McBryde (one of the reporters and voice one), William Naughton (photographer and voice two), and Ned Weaver (Jack Driscoll and voice four).

PLOT: An uneventful trip back to the great night on Broadway finally arrived. The crowd jammed four full blocks above Times Square and spilled over into the middle of Broadway. Traffic cops shook hopeless heads, twiddled helpless fingers and wearily motions taxicabs into the side streets above and below. Opening night and orchestra seats are $10. Backstage, Driscoll is wearing a tux; Ann is wearing an expensive gown. Reporters ask questions and Driscoll and Ann admit they are engaged to be married. When the curtain opens, Denham introduces people to Kong, chained to the wall with chrome steel. Ann Darrow is brought on stage to meet her captor. Photographers take pictures; the flash of the bulbs disturbs Kong greatly, who snaps chains and breaks from his bonds. Driscoll races Ann out the back door to her hotel for safety. Kong, meanwhile, crashes into the hotel lobby. The hotel detective empties his revolver into the monstrous intruder and looked incredulously at his weapon when Kong swung around in undiminished strength and crashed back to the street. The fury of Kong escapes into the street.

Episode #15, Broadcast Saturday, April 22, 1933

CAST: Peggy Allenby (Ann Darrow and Mable, the voice over the telephone), Tim Daniel Frawley (the police officer and first voice), George Gaul (Carl Denham), Taylor Graves (third voice), Horace Sinclair (second voice), and Ned Weaver (Driscoll).

PLOT: Kong kidnaps Ann and makes for the Empire State Building. Carl Denham rationalizes that the ape sought out the highest peak in the city, comparable to Skull Mountain. Planes from Roosevelt Field are careful not to fire in the direction of Ann, but Kong attempts to get the better of them. When multiple bullets rip through his heart, the ape plunges to his death. Admiring the body of Kong in the street, a police officer comments that he did not expect the airplanes to do the job. Denham replies that the aviators did not kill him. “It was beauty. As always, Beauty killed the beast.”

Closing

King Kong made a return visit to radio multiple times. On the evening of March 2, 1933*, King Kong premiered in New York at the Radio City Music Call. Broadcast over WJZ (NBC Blue Network) that Thursday evening, on a clear evening with little overcast, Graham McNamee hosted a special broadcast from 10:00 to 10:30 p.m., airtime purchased by RKO in an effort further promotion of the motion-picture to the radio audience. McNamee’s dialog over the air was scripted in advance.

* A number of reference sources on the Internet cite the New York premiere being March 7. This is obviously incorrect.

Actress Peggy Allenby

“I am speaking to you from the Musical Hall in Radio City, where we are gathered tonight to celebrate the gala opening of the thrilling picture, King Kong, by Marian C. Cooper and Edgar Wallace. This picture opens today simultaneously in both of the great theatres in Radio City. It is really an amazing sight to witness the great throngs gathered in these two theatres for this event. There are at least 10,000 people now watching the picture in the Music Hall and the new Roxy and there are thousands more in the lobbies waiting to get in. Out in the street, huge searchlights make Sixth Avenue and the cross-streets as bright as day. In the weird light, the display of prehistoric monsters on the marquee are fearsome indeed. There is a huge ape, fourteen feet tall, indulging in almost human motions. The life-size dinosaur stretches its menacing form over the gaping crowds.”

“The distinguished first night audience is typical of other famous Broadway first nights,” McNamee continued. “Stars of the entertainment world, business and political celebrities, critics and skeptics and just plain people. In a few moments I am going to see if I can’t bring to the microphone, some of these people whose names you all know.”

John Chapman, ace columnist of the New York News, appeared before the microphone, providing the radio audience advance notice of his review that would soon appear in the newspaper. Lowell Thomas followed, also providing his opinion of the gala and the movie itself. The comments of both Chapman and Thomas were scripted.

The New York engagement at Radio City’s Music Hall and the Roxy attracted a reported 50,000 people on opening day. Within the first four days, advertisements were hailing an all-time attendance record for an indoor event. The two movie theaters screened the film ten times every day.

On the evening of March 24, King Kong premiered on the West Coast. A remote broadcast over KECA from Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood, 11:30 to midnight, opening of movie on the West Coast in Hollywood. Broadcast from Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood, Harry Jackson directed the broadcast under the sponsorship of RKO Studios. Band leader Phil Harris served as master of ceremonies, interviewing a slew of personalities directly involved with the production of the motion-picture, including Merian C. Cooper, cinematographer Ernest B. Schoedsack, author, lecturer and adventurer Richard Halliburton, columnist Louella Parsons, and actors Frank Reichter, Bruce Cabot and Fay Wray. The interviews, though brief on the air, were not scripted.

On the evening of March 24, King Kong premiered on the West Coast. A remote broadcast over KECA from Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood, 11:30 to midnight, opening of movie on the West Coast in Hollywood. Broadcast from Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood, Harry Jackson directed the broadcast under the sponsorship of RKO Studios. Band leader Phil Harris served as master of ceremonies, interviewing a slew of personalities directly involved with the production of the motion-picture, including Merian C. Cooper, cinematographer Ernest B. Schoedsack, author, lecturer and adventurer Richard Halliburton, columnist Louella Parsons, and actors Frank Reichter, Bruce Cabot and Fay Wray. The interviews, though brief on the air, were not scripted.

Kong’s giant head was displayed both inside the lobby during the premiere and outside for a spell for publicity purposes. Because of the unplanned “Bank Holidays” that occurred as a result of FDR and the Great Depression, the Los Angeles premiere was delayed by over a week, with ticket prices dropped from $5.50 to $3.30.

On the evening of June 2, Jack Benny and cast performed a continuation of an on-going murder mystery, “Who Killed Mr. X?” on the weekly Chevrolet Program. Characters Holmes and Watson (pronounced Vatson, a Jewish stereotype) travel to the newly constructed Empire State Building where they do battle with King Kong. (Radio and stage actor Ralph Ashe also supplies the voice of radio’s The Shadow during the same spoof.) Howard Claney was the announcer. Alois Havrilla would not assume the announcing chore for that program until the fall.

Going forward, when guest celebrities appeared on radio programs, a mention of their accomplishments often included a reference to King Kong. When Bruce Cabot appeared on The Royal Hawaiian Hotel Show in 1934, the announcer mentioned his appearance in Midshipman Jack (1933) and King Kong (1933). When Fay Wray appeared as a guest on the Jimmy Fidler radio program in 1934, Hollywood on the Air, she talked about the technical challenges involved during the production of King Kong. When the actress appeared on 45 Minutes in Hollywood on the evening of May 6, 1934, she discussed the movies she enjoyed making, including King Kong… joking that the giant ape was the most difficult to take action from the director.

In 1963, Golden Records released a commercial LP dramatizing the movie scenario. New York actors Elaine Rose, Ralph Bell, Nat Polen and Dan Ocko supplied the voices. This recording, split into two parts, has been mistaken many times as surviving chapters from the 1933 radio serial. A seven-minute audio recording used to promote the movie was made by RKO in 1933, syndicated via transcription disc to local radio stations across the country, does exist in collector hands. The announcer asks those by the radio speakers to listen to the horrific sounds of Kong battling a ferocious dinosaur, and the screams of Fay Wray through the music of Max Steiner. Audio clips from the movie are featured prominently. “King Kong is coming! The picture that staggers the imagination!” the announcer proclaims.

Again, the 1933 radio serial does not exist in recorded form. You can listen to the 1963 Golden Records on YouTube, as well as the seven-minute 1933 radio advertisement.

Hollywood 360 Schedule

4/2/22

The Shadow 11/5/39 Mansion of Madness

The Aldrich Family 1/22/42 Girlfriend

Have Gun-Will Travel 11/15/59 The Fair Fugitive

The Halls of Ivy 2/24/50 Student Thief

Jeff Regan, Investigator 10/26/49 The Lady Who Wanted to Live

4/9/22 (repeat of 4/10/21)

My Friend Irma 12/1/47 Reward

Richard Diamond, Private Detective 3/14/52 The Dixon Case

The Adv. of Maisie 11/9/50 Restore-o Rejuvenator

Space Patrol 12/6/52 The Space Shark

Rocky Jordan 7/17/49 The Race

4/16/22

Bold Venture 3/26/51 Deadly Merchandise

The Jack Benny Program 2/16/47 w/ guests, Ronald & Benita Colman

Let George Do It 11/8/46 The Robber

Gunsmoke 4/4/53 Jayhawkers

Philco Radio Time 1/15/47 w/ Bing Crosby and guest, Al Jolson

4/23/22

Richard Diamond, Private Detective 2/1/52 The Garibaldi Case

The Burns & Allen Show 10/26/43 w/ guest, Hedy Lamarr

Dimension X 6/10/50 The Green Hills of Earth

Top Secret 8/13/50 The Case of the Tattooed Pigeon

Wild Bill Hickock 12/26/52 Ruins of Black Canyon

4/30/22

The Amazing Mr. Malone 6/15/51 Early to Bed, Early to Rise

The Sealed Book 6/10/45 The Ghost Makers

The Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis Show 6/2/53 w/ guest, Jeff Chandler

The First Nighter Program 2/12/48 Love Is Stranger Than Fiction

Tales of the Texas Rangers 4/19/50 By Just a Number

© 2022 Hollywood 360 Newsletter. The articles in the Hollywood 360 Newsletter are copyrighted and held by their respective authors.