NEWSLETTER | VOL. 24, April 2023

Welcome to this month’s edition of The Hollywood 360 Newsletter, your place to get all the news on upcoming shows, schedule and interesting facts from your H360 team!

Carl’s Corner

by Carl Amari

The detective character, Sam Spade, was created by writer Dashiell Hammett for his crime story The Maltese Falcon. Spade was a hard-boiled detective with cold detachment, a keen eye for detail and unflinching determination to achieve his own justice.

The character is most closely associated with actor Humphrey Bogart who played Sam Spade in the third and most famous film version of The Maltese Falcon. The Maltese Falcon was adapted for radio, three times, twice in 1943 and once in 1946. On February 8th, 1943, Edward G. Robinson played Spade on The Lux Radio Theater and on September 20th, 1943, Bogey reprised his film role on The Screen Guild Theater. Then, again, on July 3rd, 1946, Bogey played Spade before the radio microphones on Academy Award Theater.

William Spier, one of radio’s top producers, brought The Adventures of Sam Spade, Detective to the airwaves starring newcomer Howard Duff with Lurene Tuttle as Spade’s secretary, Effie Perrine. The selection of young Duff for the hard-hitting detective was perfect casting, his success was immediate, and Hollywood began predicting important things to come for this new personality. Almost immediately the radio program became popular earning a steady weekly following of radio listeners who tuned in each week to enjoy the mysteries (occasionally adapted from Hammett short stories). Duff took a considerably more tongue-in-cheek approach to the character than the novel, the movie or the earlier radio incarnations. The enormous success of the Sam Spade radio program spawned a series of comic strips, magazine articles and radio cross-overs, not to mention numerous radio programs attempting to cash in on the Sam Spade craze by offering sound-alike shows. Dashiell Hammett lent his name to the radio series but did little more than cash the checks sent to him for the privilege. The series ran for 13 episodes on ABC and for 157 episodes on CBS from 1946-1950. In 1947, Spier and scriptwriters Jason James and Bob Tallman received an Edgar Award for Best Radio Drama from the Mystery Writers of America. For most of its run it was sponsored by Wildroot Cream-Oil (which Lisa Wolf still uses on her delicate hair : ).

Howard Duff starred as Sam Spade on radio until 1950, when CBS decided to cancel the top-rated series due to Hammett being accused of Communist ties. NBC quickly picked up the series and cast Steve Dunne in the title role. Two of Hammett’s other literary creations, The Thin Man and The Fat Man, also had popular radio runs.

Her success can be measured in many forms. In 1968, Lucille Ball was reported to be the richest woman in television, having earned an estimated $30 million. She remains the only Hollywood celebrity to grace the front of two postage stamps. A 34-cent stamp, issued in 2001 and a 44-cent stamp, issued in 2009.

LEND ME YOUR EARS | THIS MONTH’S SONG: THE BOXER, Simon & Garfunkel

RELEASED: 1969

by Lisa Wolf

Click here to watch on YouTube.

“I think the song was about me: everybody’s beating me up, and I’m telling you now I’m going to go away if you don’t stop. By that time we had encountered our first criticism. For the first few years, it was just pure praise. It took two or three years for people to realize that we weren’t strange creatures that emerged from England but just two guys from Queens who used to sing rock ‘n’ roll. ~ Paul Simon

“I think the song was about me: everybody’s beating me up, and I’m telling you now I’m going to go away if you don’t stop. By that time we had encountered our first criticism. For the first few years, it was just pure praise. It took two or three years for people to realize that we weren’t strange creatures that emerged from England but just two guys from Queens who used to sing rock ‘n’ roll. ~ Paul Simon

“The Boxer” is a song written by Paul Simon and recorded by Simon and Garfunkel, from their fifth studio album, Bridge over Troubled Water (1970). “The Boxer” was the follow-up to one of their most successful singles “Mrs. Robinson”.

The chorus of the song is wordless, consisting of an eight-time chant of “lie-la-lie” accompanied by a heavily reverbed drum. Simon stated that this was originally intended only as a placeholder, but became part of the finished song. Simon felt that the essentially wordless chorus gave the song more of an international appeal, as it was universal.

“The Boxer” took over 100 hours to record, with parts of it done at Columbia Records studios in both Nashville and New York City. The chorus vocals were recorded at St. Paul’s Chapel at Columbia University in New York. The church had a tiled dome that provided great acoustics. Simon found inspiration for this song in the Bible, which he would sometimes read in hotels. The phrases “workman’s wages” and “seeking out the poorer quarters” came from passages.

Bob Dylan recorded a version of “The Boxer” on his 1970 album Self Portrait.

Click here to watch on YouTube.

On June 3, 2016 at his concert in Berkeley, California, Paul Simon stopped singing partway through “The Boxer”, to announce breaking news: “I’m sorry to tell you this in this way, but Muhammad Ali passed away.” He then finished the song with the last verse: “In the clearing stands a boxer and a fighter by his trade…”

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SERGEANT PRESTON OF THE YUKON

by Martin Grams

On the subject of Canadian Mountie fiction, author and historian David Skene-Melvin described it best: “Canada never had a Wild West because the Mounties got there first.” Ironically, a large amount of Northern fiction is the work of non-Canadians. Nevertheless, Skene-Melvin writes “Just as the Western is widely regarded as emblematic of American culture, it can be argued that the Northern is the only truly indigenous Canadian art form, even if most of its exponents have been foreigners.” One such example was the radio and television program, Sergeant Preston of the Yukon.

Prior to the radio program, Canadian Mounties were commonplace in pulp magazine, book form, and motion pictures. Like the Western genre, Canadian Mountie fiction was a variation-on-a-theme with a limited number of plots in a setting that placed limitations on the number of crimes that could be investigated by men of the scarlet tunic. For certain authors, the establishment of a recurring hero was the romantic aspect of the Northern fiction. For motion-picture producers, the heroes would inaccurately wear a red coat in temperatures forty degrees below zero, with the hope that the cinema goers applied suspension of disbelief. Inspired by the Rin-Tin-Tin craze that dated back to the silent era, many of the Canadian Mounties had a canine sidekick that received top billing, which sometimes made the lead actor wonder who got paid more.

In 1936, MGM produced and released Rose Marie, which established a Hollywood fashion statement of Canadian Mounties who displayed impressive vocal chords among the canyons, serenading the white pines. Beginning in 1935, Zane Grey’s King of the Royal Mounted premiered in the newspapers, a long-running comic strip focusing on the adventures of Corporal Dave King, who would later be promoted to Sergeant over the course of the series. From 1936 to 1938, CBS radio aired a daily serial, Renfrew of the Mounted, which dominated Canadian Mountie fiction on network radio coast-to-coast. Historical hindsight applied, with all of these ingredients it comes as no surprise that by 1938 most cowboy stars tried their hand at playing the role of a Canadian Mountie. This included (but was not limited to) Tom Tyler, Charles Starrett, and Russell Hayden.

When Wonder Bread failed to renew their sponsorship for Renfrew of the Mounted, it was George W. Trendle in Detroit who believed the vacancy could be filled with another Canadian Mountie. Enter stage left, Tom Dougall, a staff writer who was responsible for the daytime soap opera, Ann Worth, Housewife, which aired over the Michigan Radio Network. The soap opera came to a close in 1938, and Dougall was supplementing his time scripting The Lone Ranger and The Green Hornet on an average of once a week.

According to his unpublished autobiography, Bar Talk and the Talkers and the Talked About, Dougall recounted that historic moment in late summer 1938 that spawned the creation of Sergeant Preston of the Yukon: “My economic status improved during the thirties as most people’s did, but the reason, in my case, was that I turned to writing to augment by acting income… finally Trendle sent me a memo. ‘Give me a series in which the hero is a dog.’ He always thought Silver was the hero of The Lone Ranger. Well, the dog had to be a working dog and Lassie has the sheep market tied up, so I called on the shades of [Thrills of the Secret] Service and Jack London and made King a sled dog. Except that King was Mogo originally. Trendle renamed him King, after his partner.”

After reading the first year’s worth of radio scripts, it was evident that Tom Dougall was borrowing plots from various Canadian Mountie fiction, including Jack London. With Dougall confessing where he borrowed material, we can easily assume that King was inspired by the canine hero from London’s 1906 novel, White Fang. The story details White Fang’s journey to domestication in the Yukon Territory and the Northwest Territories during the Klondike Gold Rush. The title character was a wolf-dog hybrid who also served as the novel’s protagonist and written from the viewpoint of the titular canine character. Dougall did not hesitate to confess: “I’ve always borrowed. I’m not an original writer. Once, during my Lone Ranger days, an old character actress told me that I was only a fair writer but that I had an excellent memory. I used the plot of Hamlet with various modifications as the basis for six Lone Rangers.”

In July and August of 1938, prior to the formation of Challenge of the Yukon, Tom Dougall wrote three radio scripts titled Ringside. While the initial title might suggest a circus theme, the daytime drama concerned a boxer and his manager – with strong shades borrowed from the newspaper comic strip, Joe Palooka, thrown in for good measure. But when this failed to reach fruition in WXYZ, the flagship station of the Michigan Radio Network, Dougall answered the call of George W. Trendle to create a series of Canadian Mountie adventures.

In late 1938, five radio scripts numbered one through five were drafted and edited, supervised by Trendle and director Charles Livingstone. Initially the series was proposed to be called The Call of the Yukon, then re-titled Morgan of the Northwest Mounted with the hero named Constable Morgan. Script number two suggests the name Constable James Marshall of the Northwest Mounted Police. Before the series premiered on the evening of January 3, 1939, the program was titled Challenge of the Yukon and formulated to the characters we know today as Sergeant Preston and his wonder dog King. (The name “Yukon King” was not established in the early years of the radio program, referred to simply as “King.”)

The first 16 episodes from January through February 1939 provided an epic with Preston’s lead sled dog named Mogo taking the lead. After rescuing what he initially mistook as a wolf, who would later be christened “King,” Preston embarked on a dangerous route to apprehend a criminal. An exchange of gunfire resulted in the death of Mogo. King would be nursed back to health and within a few episodes become a loose leash dog. (This meant King was never tethered to the sled like the rest of the dogs, running free to lead the pack.) There was no origin for Sergeant Preston, as he was already an experienced Canadian Mountie beginning with the first episode of the series. (More than ten years after the premiere of the radio program, Fran Striker would later write an origin for Sergeant Preston and a different origin for Yukon King.) For the first two years of the radio program, a French-Canadian named Pierre was a human sidekick, who also agreed with Preston that King may have a bit of wolf in his DNA.

The early adventures were more adult in nature, length multi-episode story arcs, downsized to two-parters through January and February of 1940, eventually settling on single-episode stories by spring of 1940. Romantically, fans of the radio program would like to think the series aired coast-to-coast from day one, but the fact remains (and through producer George W. Trendle’s admission) the series was a difficult sell to potential sponsors. For the program’s first seven years, the series was heard regionally over the Michigan Radio Network. It was not until the fall of 1943 that the program was syndicated via transcription disc but with limited distribution.

STATISTICS

1,260 radio broadcasts aired from 1939 to 1955.

January 3, 1939 – first episode of the series

May 30, 1940 – first episode to be assigned a script title

May 29, 1943 – first episode to be recorded via transcription

November 14, 1946 – first national broadcast over ABC

June 12, 1947 – first 30-minute broadcast of the series

September 13, 1948 – first broadcast sponsored by Quaker Oats

November 13, 1951 – program officially re-titled Sergeant Preston of the Yukon

By official count, two audition recordings are known to exist. The first 284 episodes were never recorded. Of the 976 episodes transcribed from 1942 to 1955, only 74 are not circulating among collectors. While this means only 7.5 percent of the recordings are considered “lost,” yet it is believed that most of them do exist and have not made their way into collector hands – yet.

All of the radio scripts from the first few years were scripted by Tom Dougall, who was an excellent writer, despite what misgivings he had for his talent. Dougall could write prose and dialogue that was above average for radio production. Sometime circa 1942, however, Dougall went into the service and Fran Striker, then scripting The Lone Ranger and The Green Hornet, filled in temporarily. Striker was unable to handle the payload, so his solution was to recycle plots from The Lone Ranger and make them into Canadian Mountie adventures. Betty Joyce, an aspiring script writer who was being taught the style and format, and was scripting commercials at the time, was coached into the position. Joyce, too, adapted Lone Ranger plots into Canadian Mountie adventures. By 1945, Dan Beattie and Mildred Merrill were added to the script writing staff, whereupon the stories featured on Challenge of the Yukon were again original concepts.

In the spring of 1951, George W. Trendle had a conference with his attorney, Raymond Meurer, regarding the fictional character’s Intellectual Property. Sergeant Preston was a fictional Canadian Mountie and it was agreed that the trademarks that made up the character beyond the fictional name would not be strong enough to combat infringement in court. It was advised beyond the artistic logo created for use on licensed property to change the name of the radio program from Challenge of the Yukon to the name of the fictional character. Beginning with the broadcast of November 13, 1951, the name of the radio program changed to Sergeant Preston of the Yukon. Between the decision to change the name of the program and the official switch-over took more than three months because the network and the sponsor had to approve of the name change.

Once the Quaker Oats Company began sponsorship of the radio program in 1948, premiums became common during the commercial breaks. Where many giveaways were meant to convince sponsors that a large enough listenership warranted a contract renewal, Quaker Oats used these giveaways as a means of selling their product. Thus, even when premiums had no bearing on Sergeant Preston, such as College pennant cutouts (September 1948), Indian trading cards (April to May 1952), circus animal toys (February 1953), 3-D circus cards (September 1953), to sports trading cards (May 1954), listeners were encouraged to send in box tops to receive the novelties.

Gabby Hayes made multiple appearances in recorded commercials promoting the Gabby Hayes hat (November to December 1951), model totem poles (March 1952), movie viewer premium (September to October 1952), and western wagons (February to March 1953). Quaker Oats was the sponsor of The Roy Rogers Show and with so many leftover premiums, the sponsors felt the Sergeant Preston program was a perfect venue to liquidate overstock.

From October to November 1949, Bugs Bunny comic books were offered during the commercial breaks, with recordings of Mel Blanc voicing the cartoon rabbit to help pitch the Dell comics. (Dell was also the publisher of the Sergeant Preston of the Yukon comic books.)

It should be noted that there were indeed some premiums that were implemented into the radio dramas. From October to November 1950, the Mounted Police whistle was offered. A distance finder was given away in early October 1954. Yukon trail cutouts were offered from March to May 1950. From November to December 1954, the Sergeant Preston Pedometer was offered. For three episodes in February 1949, the Secret Signal Two-Way Flashlight proved to be an indispensable tool for Sergeant Preston. Oddly, and only recently discovered, there was at one time a Sergeant Preston vacation giveaway for air tours for two to Alaska and the Yukon.

Perhaps the most unique giveaway during the history of the radio program was the Yukon Land Deed, a premium featured during the broadcasts of January 27 through February 24, 1955. An enterprising employee at the advertising agency created the novel idea of purchasing 19.11 acres in the Yukon territory, for the purchase price of $1,000, so that listeners could submit a box top in exchange for a paper deed granting them ownership of one square inch of land in the Yukon. This premium was not without a legal problem, however. Weeks after the offer was first given on the Sergeant Preston of the Yukon radio program, the Ohio Securities Division ruled that Quaker Oats could not trade a square inch of the Yukon for a box top without a license to sell foreign land, so the company decided afterwards to put the paper deeds inside boxes of Quaker Oats and Quaker Puffed Wheat.

Columnists across the country picked up the story and wrote of the novel giveaway. At least eight months of newspaper articles and advertisements gave the advertising agency what may have been $1 million in publicity. Practically every program sponsored by the Quaker Oats Company on both radio and television was pitching the giveaway including television’s Contest Carnival.

Amusingly the June 1956 comic book issue of Uncle Scrooge spoofed this scenario as Scrooge McDuck acquires a deed for one square inch of land in Arizona from a cereal box giveaway and demanded the company inform him which square inch was his as he planned to drill for oil on his newly-acquired land. More amusing is the fact that in 1959 another entrepreneur decided to offer a similar giveaway for a land deed of one square inch of the North Pole… North Pole, Alaska.

Beginning in 1952, Dell produced a series of 29 comic books based on Sergeant Preston of the Yukon. The first 18 issues featured lavish oil painting artwork by Morris Gollub, an animator at Hanna-Barbera and Disney, while the remaining 11 featured publicity stills of Richard Simmons in costume from the television series. Despite the attempt to cash in on the popularity of the television rendition, all of the stories in the comic books were adaptations of the radio scripts.

Very few of the Sergeant Preston premiums and collectibles (beyond those 11 comic books) were marketed from the television rendition. Two board games, two jigsaw puzzles, a map of the Yukon, and three 1953 Decca Records were premiums from the radio program.

During the final weeks of the radio program, in the spring of 1955, George w. Trendle was looking over the prospects of a new actor who could play the role of Sergeant Preston for television. Richard Simmons, an actor who played supporting roles in motion pictures and television for more than a decade, was hired to play the title role. (According to James Garner, he and Simmons were up for the role of Sergeant Preston but Garner decided to pass to pursue film work at Warner Brothers.) Ironically, Simmons played the role of a Canadian Mountie in Republic’s King of the Royal Mounted back in 1940.

Filming commenced in the June of 1955, in Aspen, Colorado, where the snow in the higher elevation allowed for comfortable filming on location, while the afternoon temperature reached a mild 75. Simmons later recalled how a western breeze blowing in over the snow would replicate interior air conditioning. The first 16 episodes were filmed on location until Simmons was tossed from his horse and received a broken rib, temporarily shutting down production in Aspen. After which, filming was shot in California for the remainder of the season, and the remainder of the series.

The budget for the first 26 episodes was $750,000, which came to an average of $28,846 per color episode. (By comparison, The Lone Ranger was shot with an average of $22,000 per black and white episode.) For the third season, the budget rose to $1 million. Cowboy star Eddie Dew, turned director, took the helm for a large number of episodes. “Eddie was a prince of a guy, one of the nicest men that ever lived,” Simmons later recalled. “He directed all of the earlier summer episodes with the horse, and many of the winter shows.”

The television series premiered in September of 1955 over the CBS-TV network for a Saturday morning timeslot, three months after the radio program came to a close. After all 78 half-hour episodes aired over three seasons through September 1958, the program went into syndication. By July 1959, the series aired in reruns in 95 markets. In October 1963, the television series began airing in Japan.

In April of 1957, Jack Wrather purchased the rights to the radio and television series for an estimated $1.25 million. Having purchased The Lone Ranger back in August of 1954 for $3 million, and having made a small fortune on the property, Wrather had hopes of replicating the same success. (Originally Wrather was offered both The Lone Ranger and Sergeant Preston for $4 million, but Wrather only had $3 million in liquid assets at the time so he purchased only The Lone Ranger.) Wrather was the owner of the Disneyland Hotel at the time, resulting in Richard Simmons making appearances in the Disneyland theme park, in full costume. The Disneyland Hotel also had a Sergeant Preston’s Yukon Saloon complete with employees dressed as Canadian Mounties, saloon girls and a costumed grizzly bear.

For more information about the book, visit www.MartinGrams.com

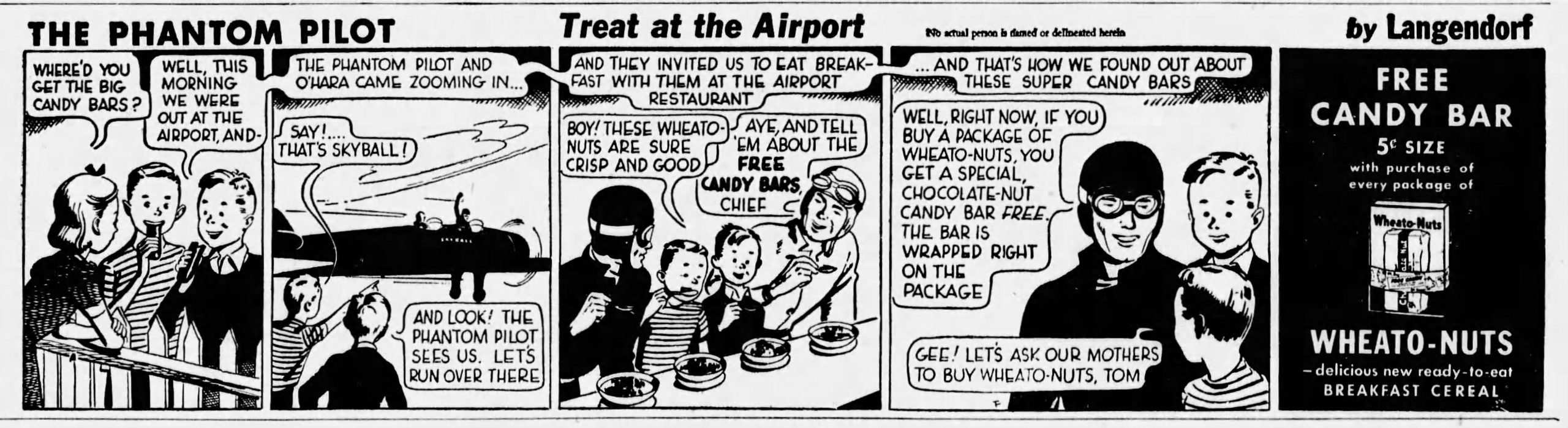

THE PHANTOM PILOT COMIC STRIP ADVERTISEMENTS

by Karl Schadow

Hollywood 360 Schedule

4/1/23

My Favorite Husband 4/1/49 April Fool’s Day

The Line-Up 6/10/52 Lobdell’s Poodle-Cut Tomato Case

Big Town 11/30/37 Parole Board

The Jack Benny Program 4/16/50 Jack Gets His House Painted

Rocky Jordan 5/15/53 The Veiled People

4/8/23

Bold Venture 3/26/51 Deadly Merchandise

The Jack Benny Program 2/16/47 w/ guests, Ronald & Benita Colman

Let George Do It 11/8/46 The Robber

Gunsmoke 4/4/53 Jayhawkers

The Philco Radio Time 1/15/47 w/ Bing Crosby and guest, Al Jolson

4/15/23

The Adv. of Sam Spade, Detective 8/8/48 The Bluebeard Caper

The Red Skelton Show 11/14/51 Travel is so Broadening

Gunsmoke 1/10/53 Word of Honor

Escape 7/11/51 The Island

You Bet Your Life 12/28/49 Secret Word: Name

4/22/23

The Milton Berle Show 3/23/48 A Salute to Spring

Fort Laramie 4/1/56 The Lost Child

The Shadow 8/21/38 Murder On Approval

Gang Busters 6/19/48 The Case of the Tennessee Triggermen

Quiet Please 3/6/49 The Man Who Knew Everything

4/29/23

The Lum & Abner Show 10/24/48 Substitute Postman

Bold Venture 6/11/51 The Tears of Siva

Candy Matson, Yukon 28209 7/7/49 The Cable Car Murder Case

Dimension X 7/1/50 A Logic Named Joe

The Saint 1/14/51 The Actor

© 2022 Hollywood 360 Newsletter. The articles in the Hollywood 360 Newsletter are copyrighted and held by their respective authors.