NEWSLETTER | VOL. 16, August 2022

Welcome to this month’s edition of The Hollywood 360 Newsletter, your place to get all the news on upcoming shows, schedule and interesting facts from your H360 team!

Carl’s Corner

by Carl Amari

Hello everyone – here’s the Hollywood 360 newsletter, August 2022 / Vol. 16. As someone on our mailing list, you’ll receive the most current newsletter via email on the first day of every month. If you don’t receive it by the end of the first day of the month, check your spam folder as they often end up there. If it is not in your regular email box or in your spam folder, contact me at carlpamari@gmail.com and I’ll forward you a copy. The monthly Hollywood 360 newsletter contains articles from my team and the full month’s detailed schedule of classic radio shows that we will be airing on Hollywood 360. Each month I’ll provide an article on one of the classic radio shows we’ll present on Hollywood 360. This month, we’ll be airing two radio episodes starring Frank Sinatra. The week of August 6th, we’ll have an episode of The Frank Sinatra Show and the week of August 13th, we’ll present Rocky Fortune, so here’s an article on old blue eyes himself, Frank Sinatra. Enjoy!

FRANK SINATRA

By Carl Amari and Martin Grams

A newspaper columnist once observed … “In the studio they cheer, they scream, they applaud, or they sigh audibly every time Sinatra is at the microphone.” In the 1940s, Ol’ Blue Eyes was the master of teen jive.

Frank Sinatra got his start singing on the radio while a singing waiter in a roadhouse called The Rustic Cabin in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. Performances there were picked up by radio station WNEW in New York on a show called Dance Parade. He was soon picked up by the Harry James orchestra in 1937, and two years later made the jump to lead singer with Tommy Dorsey’s band. Sinatra recorded 40 songs with Dorsey’s band and had his first top-ten hit with “Polka Dots and Moonbeams.” Many more were to follow.

By the Sinatra left Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra in 1942, he had become America’s top-rated male singer and starred in his own radio program.

The boyish crooner became known as the idol of the bobbysoxers. These female pop-music fans, usually in their teens, loved dancing and often wore their socks rolled down to the ankle. “Sintramania” — the love affair between “Swoonatra” and his legion of “Sintratics” — was just as passionate popular music would see later with Elvis and The Beatles.

While the bobbysoxers adored “Frankie” and his songs topped the charts, their mothers swooned over Bing Crosby. Keen to retain the loyalty of his fans, Sinatra paid close attention to his image, always wearing a formal suit with a bow tie. His use of the slang of the time emphasized his hip credentials.

During the Second World War Sinatra sang frequently on Armed Forces Radio, and through the ‘40s had numerous radio shows themed around him like Reflections (1942), Songs by Sinatra (1942-43), Broadway Bandbox (1943), The Frank Sinatra Show (44-45) and Light Up Time (1949-50).

On the radio, Sinatra adopted the same “light and fluffy” approach that his fellow singer and friend Bing Crosby had employed. He also made witty asides and indulged in banter, which suggested he had departed from the script and was ad-libbing with his celebrity guests. But Sinatra did not need celebrities to boost his image, just a verbal warm-up before he got down to the serious business of singing. Soon, it seemed as if every radio comedian wanted a crooner on their show, each of them hoping they had discovered the next Sinatra.

After each show, fans begging for his autograph would ambush the singer, but he usually declined. And yet Sinatra could be very generous: whenever he learned one of the studio musicians was in trouble, he offered financial help.

In the early 50’s Sinatra had two shows, To Be Perfectly Frank (1953) and The Frank Sinatra Show (1954). By then his recording career had begun to cool off, and he made his way out to Las Vegas to become a show performer there with his irreverent and jazzy Rat Pack.

In 2015, Sony released a 4-CD set of Sinatra’s radio performances titled A Voice On The Air (1935-55.) It’s a treat for “Sinatrics” of all ages, and old-time radio fans will love the ads for laxatives, cigarettes and hair styling products.

LEND ME YOUR EARS | THIS MONTH’S SONG: Son of a Preacher Man, by Dusty Springfield

by Lisa Wolf

“Fred Foster…called me and said, ‘I’ve got a title for you: ‘Me and Bobbie McKee,’ and I thought he said ‘McGee.’ I thought there was no way I could ever write that, and it took me months hiding from him, because I can’t write on assignment. But it must have stuck in the back of my head.” ~ Kris Kristofferson

Dusty Springfield’s 1968 hit “Son of a Preacher Man” is about a young girl who sneaks away with the preacher’s son every time his dad comes to visit. Click here to listen.

The backup vocals were by a female group called the Sweet Inspirations. They were popular female backup vocalists in the New York area, having performed on albums by Aretha Franklin, Wilson Picket and Van Morrison. Later in 1969, the Sweet Inspirations toured and recorded with Elvis Presley.

Son of a Preacher Man was written by Ronnie Wilkins and John Hurley, who originally wanted Aretha Franklin to sing it. Aretha turned down the song, because she thought it was disrespectful to preachers. She changed her mind in 1970 when she recorded a cover.

Aretha’s Version (1970)

“Son of a Preacher Man” was Dusty’s biggest hit, charting at #9 in the US. The song got a late boost back onto the charts in 1994, when Quentin Tarantino included it in his film Pulp Fiction. There is a drink called a “Son Of A Preacher Man.” It’s made with peppermint schnapps, vodka or gin, and lemonade. Sounds like a winner! Click here to listen.

THE TRUE STORY WHY JOHN HART REPLACED CLAYTON MOORE

by Martin Grams

As difficult as it is to fathom after three decades, the truth of why Clayton Moore was replaced by John Hart for the third season of the television program, and then returned to the role beginning with the fourth season, has been told with such inaccuracy over the years (especially on the Internet and social media) that it warrants retelling the facts as they appear in the archival and historical files.

By February 1951, Trendle and General Mills agreed to continue television production with a third season. Having filmed 78 episodes consecutively, making up the first two seasons of the series, Jack Chertok assured producer George W. Trendle that an additional 52 episodes could be produced but the cost of production, like the cost of any business, required an increase in budget. Trendle disapproved of the increase in budget. In August of 1951, the Apex Film Corporation (owned by Chertok) created a breakdown of the first 78 television productions, to verify that Chertok’s company truly lost $29,681.60 in the deal. The average cost per episode was $11,547.20. General Mills was contracted to pay $10,000 per episode for the first 52 episodes, and $13,500 per episode for the additional 26. Chertok agreed to swallow the financial loss knowing that when the programs went into reruns later, when General Mills decided to no longer sponsor the program, he would recoup some of the loss in the form of rerun residuals and thus make a profit in the long run.

Jay Silverheels, meanwhile, did not want to wait around for a call to be on hand to play the role of Tonto when he could be making motion-pictures, so Trendle wrote out a check and a two-page agreement stipulating pay of $150 a week from January 1, 1951 to March 31, 1952, with a $2,500 signing bonus. This would expire once filming began for the television program, whereupon his contract for a weekly salary during production replaced this contract. (By 1954, Silverheels was making $650 per week, and $325 in between filming of seasons.) No such contract was provided to Clayton Moore, whose agent insisted to Trendle that offers to do movies were more lucrative.

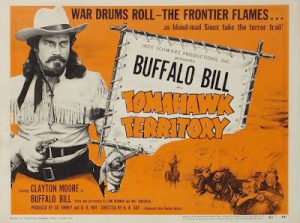

Sure enough, Clayton Moore signed to play a role in Columbia’s Hawk of Wild River, a Durango Kid western, in which Charles Starrett is sent to Wild River to recover stolen gold and finds the town terrorized by The Hawk (played by Moore) and his outlaw gang. Moore kept busy playing supporting roles at Columbia and Republic, including the Allan “Rocky” Lane western, Captive of Billy the Kid, and the title role in Buffalo Bill in Tomahawk Territory for United Artists. On Halloween 1951, Clayton Moore sent George Wallace to St. Joseph’s Hospital with a broken nose following a screen brawl with Moore (courtesy of a Lone Ranger punch to the face) while filming Radar Men from the Moon at Republic.

In late August 1951, Trendle flew to California to lineup a deal with a different production company for the new season of The Lone Ranger, as well as a pilot for both Sergeant Preston of the Yukon and The Green Hornet. He attended meetings with a number of television producers, including the Samuel Goldwyn organization, an executive under Herbert Yates at Republic, and someone at RKO Studios only to discover that while all parties were interested in a Lone Ranger movie shot in color, the studios merely wanted to perform the task of distributor, and provide the sound stages for filming, while receiving a distribution contract involving a percentage of the gross receipts. None wanted to invest in television, let alone a third season to what was already an established success on the small screen. (Yates never believed there would be a financial return with television like the movies, offering to invest in a cliffhanger serial. Trendle rejected the offer.) Disappointed, believing everyone’s math was all wrong, and coming to the realization that many studios were simply acting as a distributor for independent productions, Trendle went back to Jack Chertok and agreed on the increase in budget to produce a third season.

There is nothing evident to suggest animosity between George W. Trendle and Clayton Moore. Trendle was indeed critical of Moore’s portrayal, always in the form of letters to Jack Chertok, instructing the filmster to pass suggestions on to the actor.

Trendle sought a visual interpretation of the radio program, once expressing pleasure that Moore had gotten his voice down to a level mimicking Brace Beemer’s. Trendle suggested Moore keep his elbows down when riding Silver. “One of the rules of good horsemanship is to keep the elbows down when riding. I notice that a lot of the cow punchers seem to keep their elbows almost horizontal and you have a tendency to do that more or less in your riding. It shows lack of balance… Not only that, but with your elbows down you are closer to that gun on the lower hip, which the real fast gunfighters bore in mind when riding.”

Trendle’s repeated criticism of Moore would climax in April 1950, when he told Jack Chertok that he listened to the television show with the film turned off and the sound on. “I agree that the fellow is getting so far away from Beemer it isn’t funny, and that is a thing I am afraid we will have to discuss. The man is a fair Lone Ranger but nothing to brag about, and if he does not try to cultivate the Beemer voice more closely, I am afraid we are going to be in the position of looking around again.” Chertok debated: “It is still the old, old problem that we have to face, regardless of what man is playing the  Ranger – including Beemer himself, that he cannot talk as slowly on the screen as he does on the radio. But I repeat, we will do our best.”

Ranger – including Beemer himself, that he cannot talk as slowly on the screen as he does on the radio. But I repeat, we will do our best.”

Throughout the fall of 1951, industry trade papers reported a new actor was being sought for The Lone Ranger, but no explanation was given. Both officially and unofficially, Clayton Moore was never fired, even though he once used the phrase in his autobiography. Moore was simply unavailable to play the role for the third season.

“No one connected with The Lone Ranger ever told me why I had been fired – and I never asked. That may seem strange, but I wasn’t the sort of person to go in and make a scene about something like that,” Moore later recalled in his autobiography. “Such things happened in show business all the time. You got a part or lost a part, sometimes just on the whim of a producer or because the show was taking a new turn.” Moore never made any salary demands, and the only indication to suggest the casting change was Trendle’s insistence that someone better could be found – someone more in line with the iconic image Trendle envisioned.

Enter stage left John Hart. Tall and athletic, Hart began his screen career in 1937 playing small bit parts, and like most actors worked his way up the Hollywood ladder. An avid surfer who also served combat duty during the Second World War, he returned to Hollywood after the war and scored the title role of the Jack Armstrong cliffhanger serial for Columbia Pictures in 1947. Hart got the role because George W. Trendle confessed that Hart’s voice was closer to Brace Beemer’s than Moore.

“I don’t know how many guys they looked at to do The Lone Ranger, but they picked me,” Hart later recalled to author Tom Weaver. “They ran all those Red Ryders where I had good heavy-duty parts and did a lot of horse-backing. I was a good-looking, young, husky guy who could do all this stuff, and also do lines. I was a pretty good actor. When I first started out, I got a lot of bad advice about playing the part. I tried the bad advice for about one or two shows and then I said, ‘The hell with that. I’ll do it my own way.’ They wanted me to be like a stiff Army major, and it was all wrong. So I just forgot that and slipped into the part, and everybody loved it.”

Compared to Clayton Moore, Hart was stiff and monotone with his delivery. Moore’s body language and way of speaking was natural, more fluid. Hart slouched in the saddle. Unlike the first two seasons, many of the teleplays were original stories instead of adaptations of the radio scripts. This resulted in less comradeship between The Lone Ranger and Tonto, with Tonto relegated down to sidekick status and a spotlight on John Hart as a charismatic hero. For many viewers, this cut much of the on-screen chemistry that was predominant on the first two seasons.

Like Clayton Moore before him, as soon as filming completed for the television season, John Hart quickly found work for motion-pictures and serials, including a brief role in Columbia’s Steel of the Royal Mounted, which would be re-titled before theatrical release as Gunfighters of the Northwest. Clayton Moore and Jock Mahoney were playing the leads in that same serial.

In chatting with Jack Chertok by letter, George W. Trendle expressed disappointment with John Hart in the role, having viewed the entire season’s worth of episodes, and agreed Clayton Moore would be better suited if he was available to return to the role. Clayton Moore, according to Trendle, resembled radio’s Brace Beemer closests in both mannerisms and voice. By then Moore had a new agent, Earl McQuarrie, who was also representing Jay Silverheels. Just as Moore was never told why he was not brought back for an additional season, Hart was never told why he was being replaced after 52 episodes. Trendle was reluctant to admit to Moore personally that he was better suited than Hart, but instead reaffirmed what he expected from of the actor both in front and in back of the camera. Moore had no misgivings and returned to the program.

JOHN CROSBY: Radio Critic Extraordinaire

by Karl Schadow

The 1946 George Foster Peabody Award Citation read:

“Radio is one of the liveliest of the popular arts, as such, it deserves more intelligent and restrained attention in the press. If it is to be a great art, it must stimulate and challenge great critics. The Peabody Committee congratulates the New York Herald-Tribune for the space accorded John Crosby; it congratulates John Crosby in this special award for the liveliness and pertinence of his radio criticism. More power to his elbow!”

This was well-deserved recognition for a man who may be only known today by broadcast historians. Occasionally his reviews are posted on various social media platforms, where as you can imagine, the comments range from the wildest cheers to the most obnoxious boos. Agree or not agree with him, this author considers John Crosby to be the top pundit of Radio’s Golden Age.

Crosby’s column in the New York Herald-Tribune commenced in May of 1946 and continued into 1962. When television became the norm, Crosby turned his focus to the small screen activities. Instead of writing about this critic, let us read his own words. The following excerpts are culled from various programs.

THE DAMON RUNYON THEATRE (May 22, 1950):

“I am an incurable addict of Damon Runyon stories . . . Happily, the producers have stuck very close to the originals (Tampering with a Runyon story is a penal offense in some states.)” Regarding John Brown’s role as Broadway and the cast’s performances: “… he reproduces almost the exact quality of Mr. Runyon’s first person singular guy . . . They handle lines…as if the present tense were the only one they’d heard of.”

FATHER KNOWS BEST (November 21, 1949):

“Robert Young who plays father is a far more expert comedian than I realized . . . his comments to his children are satiric rather than explosive as is the case with most radio fathers . . . I can’t say much as much for June Whitley who plays mother. Next to Young she is pretty dim and contrived and its rather hard to understand why so pale a creature should have the upper hand in this house.”

CRIME PHOTOGRAPHER (April 15, 1949):

CRIME PHOTOGRAPHER (April 15, 1949):

“Casey is unusual in lots of ways. That title, for example. We haven’t any crime photographers around this shop. Besides bodies, they’re required to photograph prize winning dahlias, Herbert Bayard Swope and Jackie Robinson sliding into second base, all routine assignments Casey wouldn’t touch . . . is a high rated show for reasons I’ll never understand.”

THE BICKERSONS

From The Drene Show (May 25, 1948):

“Just how pretty Miss Langford contrives to transform herself so convincingly into this venomous witch is her own little secret. She nags with the whining persistence of a buzzsaw, aquality that can barely be suggested in print. Mr. Ameche responds in accents of tired loathing which could hardly be approved upon, though they well may cost him the women’s vote . . . I’d like to go on record as saying I think the Bickersons very funny. In a medium which strives so desperately to spread sweetness and light, in which every wife is an angel of tolerant understanding and every husband a dumb but lovable, the fighting Bickersons are a very refreshing venture in the opposite direction.”

QUIET, PLEASE! (March 12, 1948):

“… a rather remarkable series of dramas whose unexpected twists and curious inflections put them almost in a class apart . . . Some of these stories are almost parodies of other radio programs except they are too ingenious to be entirely satiric … Above all they are pure radio.”

In 1952, Crosby published a book Out of the Blue which contained some 130 reviews. It is certainly worthwhile reading. Did Crosby review your favorite or least favorite program? Contact this author for further information at khschadow@gmail.com

Hollywood 360 Schedule

8/6/22

The Burns & Allen Show 2/8/44 w/ guest Adolph Menjou

The Mysterious Traveler 1/10/50 Survival of the Fittest

Casey, Crime Photographer 1/22/48 Ex-Convict

The Frank Sinatra Show 10/17/45 w/ guest, Gene Kelly

Hopalong Cassidy 1/8/50 Rainmaker at Eagle Next Mountain

8/13/22

The Whistler 5/12/48 Chain Reaction

The Adv. of Philip Marlowe 2/14/50 The Grim Echo

Frontier Gentleman 6/1/58 Duel for a School Marm

My Friend Irma 10/18/48 Irma Loses Her Bosses Glasses

Rocky Fortune 1/19/54 Museum Murder

8/20/22

The Shadow 4/6/41 Murder From the Grave

Life With Luigi 3/4/52 Luigi May Lose His House

Tales of the Texas Rangers 9/30/51 Death Shaft

The Cavalcade of America 5/5/47 School for Men

David Harding, Counterspy 4/11/50 The Mile-High Murders

8/27/22

Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar 6/21/58 The Virtuous Mobster Matter

Fort Laramie 5/27/56 Sergeant’s Baby

Barrie Craig, Confidential Investigator 3/2/55 Sweet Larceny

The Halls of Ivy 4/28/50 The Scofield Prize

The Screen Guild Theater 1/7/46 The Lost Weekend

© 2022 Hollywood 360 Newsletter. The articles in the Hollywood 360 Newsletter are copyrighted and held by their respective authors.