NEWSLETTER | VOL. 2 JUNE 2021

Welcome to this month’s edition of The Hollywood 360 Newsletter, your place to get all the news on upcoming shows, schedule and interesting facts from your H360 team!

Carl’s Corner

by Carl Amari

Hello everyone – here’s the Hollywood 360 newsletter, June 2021 Vol. 2. As someone on our mailing list, you’ll receive the most current newsletter via email on the first day of every month. If you don’t receive it by the second day of the month, check your spam folder as they often end up there. If it is not in your regular email box or in your spam folder, contact me at carlpamari@gmail.com and I’ll forward you a copy. If you’d like to sign up a friend to receive this free monthly newsletter, use the bar at the top to sign them up. You’ll notice that we include a schedule of all the classic radio shows we’ll present on Hollywood 360 each month. I’ll write an article on one of the classic radio series that we’ve scheduled to air and include a photo. The week of June 19th, 2021 we’ll be airing an episode of Fibber McGee & Molly so here’s my article on this great comedy series and a photo …

Fibber McGee & Molly

In the early thirties, real life married couple Jim and Marian Jordan tried their hands with the fledging medium of radio. From Luke and Mirandy, The Smith Family and Smackout, the two developed neighborly characters that quickly defined the persona of everyday life. Teeny was the endearing little tyke who talked about her doll and her female cat named “Percy.” Mrs. J. High-Hat Upson was the highbrow who owned a mansion on the hill and clashed with any man who poked fun at her way of living. Bertha Boop was a glamorous Hollywood star who grew weary of the glitter and sham of Hollywood and returned home to seek a suitor. Squire Lovejoy was the wealthy old chiseler with get-rich-quick schemes. As in the days of the early 1930s, anyone listening within earshot of the radio speakers would quickly associate with the fictional characters and to them, they were real people.

By 1935 those same fictional characters evolved (sometimes involving name changes) and Jim and Marian Jordan created what would become the endearing Fibber McGee and Molly program. Fibber and Molly lived at 79 Wistful Vista, a branch of suburbia with friendly neighbors who stopped by to visit them and offer sage wisdom to Fibber’s craftsmanship — whether it be fixing the mail box or hanging Christmas lights. A slice of American life with a movie house in town, a department store, a friendly mailman who never hesitated to take a moment and chat with the McGees, and a gossip society consisting of a little old ladies’ sewing circle. Fibber McGee and Molly today remains evident why the program represented the best of Main Street U.S.A.

Under the brilliance of script writer Don Quinn, Fibber developed into a whimsical windbag often telling tall tales of his youth: “Punch-bowl McGee, I was known as in those days…” Molly never called her husband, “Fibber,” – instead, she referred to him as either “McGee,” “himself” or “dearie.” He, in return, would refer to her as “kiddo,” “tootsie” and “snooky.” Pet names were rarely used on radio because it broke the unwritten rule that radio listeners would be confused as to who was being referred to by nickname.

For a short time their next-door neighbor was Throckmorton P. Gildersleeve, who displayed a smug personality complex and became the perfect foil for windbag McGee. Their long-standing feuds once culminated with a duel involving water hoses. Harold Peary played the next-door neighbor character with such bravado that NBC ultimately gave way to a “spin-off,” The Great Gildersleeve, which became a long-standing radio program of its own success. The McGees also had a maid for a spell, Beulah, who also branched off with a short-lived “spin-off.”

When the war came, Fibber and Molly contributed to scrap drives, war bond promos and in one episode Fibber discovers there is a foreign spy operating out of Wistful Vista. Every wartime broadcast was a subtle reminder that everyone, radio listeners included, had a service to provide to their community to help win the war. During the post-war years familiar characters were dropped from the program to make way for new ones. Boomer and Nick DePopolous stepped aside for Officer Mulhooney and Sgt. Clancy, creating an opportunity for Molly to demonstrate her thick Irish brogue. Jim Jordan Jr. tried his hand at acting for one episode in 1946, and the McGees added a temporary house servant, a Filipino houseboy, displaced as a result of the war, named Albert.

In 1950, after 15 consecutive years with sponsor The Johnson Wax Company, the Fibber McGee and Molly program gained a new sponsor: Pet Milk. Their association lasted two years, followed by one year with The Reynolds Aluminum Company. In 1956, the Jordans closed down operations and America lost the couple-next-door. Long gone were such staples as Harlow Wilcox and the Kings Men, Mayor LaTrivia, The Old Timer and Wallace Whipple. The neighbors moved on and the neighborhood was never the same.

TRIVIA:

In the broadcast of February 15, 1939, Fibber was flabbergasted to learn that their house was number 81, not 79. (Which makes sense since Gildersleeve, their next-door neighbor, lived at 83 Wistful Vista). Fibber was trimming the overgrown lilac bush, which obscured the house number. After a few jokes about the situation it was decided before the end of the program to eliminate confusion and maintain the 79.

L-R: Jim Jordan and Marian Jordan

LEND ME YOUR EARS | THIS MONTH’S SONG: BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY, QUEEN

by Lisa Wolf

“The heavy bit was a great opportunity for us to be at full pelt as a rock band. But that big, heavy riff came from Freddie, not me. That was something he played with his left hand in octaves on the piano. So I had that as a guide—and that’s very hard to do, because Freddie’s piano playing was exceptional, although he didn’t think so. In fact, he thought he was a bit of a mediocre piano player and stopped doing it later on in our career.” ~Brian May

Queen left-to-right: Roger Taylor, John Deacon, Freddie Mercury, Brian May

The story of “Bohemian Rhapsody”—or “Bo Rhap,” as it is known by Queen fans, began in 1968, when Freddie Mercury was a student at London’s Ealing Art College. He composed an opening line—“Mama, just killed a man”—but no melody. The song’s title is a twist on Franz Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody”, and runs five minutes and fifty-five seconds in length. “Bo Rhap” is actually three songs strung loosely together. Mercury said, “it was basically three songs that I wanted to put out and I just put the three together”. The song has no chorus, but consists of three main parts: a ballad segment, an operatic passage, and a hard rock section.

Mercury stated, “It’s one of those songs which has such a fantasy feel about it. I think people should just listen to it, think about it, and then make up their own minds as to what it says to them.”

Thanks to the film Bohemian Rhapsody, Queen had an important role at the 2019 Oscars ceremony. The band (with the amazing Adam Lambert on vocals) opened the show. Nominated for 5 Academy Awards, the film won 4.

Vince’s Verbiage

by Carl’s Crabby Brother Vince

Hello there OTR fans, Carl’s crabby brother Vince here. I just want to try to explain why Carl calls me his crabby brother. It surely isn’t because I’m always crabby. In fact, I think he would say I’m one of the funniest people that he knows. It’s been a running joke between him & I for many years, probably stemming from my reaction when people do things that aren’t too smart or lack common sense. Humor, I’m sure Carl would tell you is a big part of his and my lives. To me, humor keeps you young. When I was about 8 years old in 1959, TV station WGN started showing The Three Stooges. They would show 2 or 3 episodes or “shorts” as they call them. Each short was about 18 to 20 minutes in length. The show was hosted by an elderly gentleman by the name of Andy Starr. Well, Andy Starr was not really an elderly man, and that wasn’t even his real name. His real name was Bob Bell and he was much much younger. I’m sure some of you will remember that Bob Bell would later take on the role of Bozo the Clown in the Chicago area. A character he would play for many years on Bozo’s Circus. Now getting back to the show. It came on at 3:30 pm. School let out at 3:15 pm. Being that Spencer school was only 3 blocks from where I lived I would run all the way home as fast as I could so I wouldn’t miss one minute of my new found love, The Three Stooges. I still watch them to this day, even bought the remastered DVD’s of them in chronological order from the 1st short thru all the ones with Curly in them. Now in the past year I have turned my 7 year old granddaughter Mia on to them and we laugh together. As many times as I’ve seen each one I still get a kick out of them and I think it helps keep me young.

Observations on the Obscure: Radio Scribe Scott Bishop

by Karl Schadow

There were literally hundreds (if not a few thousand) program writers during radio’s Golden Age. While Fran Striker and Irna Phillips may readily come to mind as two prominent authors, there were many others skilled at this craft who deserve our attention; and that despite achieving success in the industry their careers have not been extensively studied. This article will serve as a brief introduction to the accomplishments of Scott Bishop.

Though he is best-known for work under this byline, the Bishop moniker is actually a pseudonym of George Marion Hamaker. Born at Topeka, Kansas on May 21, 1912, Hamaker graduated from St.Marys College (St. Marys, Kansas) and entered radio in 1933 at hometown station WIBW. As a member of the continuity staff, he wrote everything from commercials and public service announcements to comedies and dramas. His forte was mystery including such series as Krime Klan and The Crime Patrol. The latter was broadcast via a network of Kansas stations. He also penned scripts for the weekly WIBW Players, the station’s premier endeavor.

Scott Bishop

By 1936, his experience allowed him to secure a position on the continuity staff of the Oklahoma City’s WKY. His passion for the mystery genre continued with Calling Detective O’Leary (a revamping of The Crime Patrol) and also expanded into horror with Tales of the Witch Queen, which he co-authored with Richard Breen. This duo also collaborated on the regional daytime serial, The Heart of Martha Blair. It was at WKY that Hamaker, utilizing the Scott Bishop appellation achieved national acclaim with Southern Rivers and Dark Fantasy, as both were carried coast-to-coast via NBC. The former, a variety program featured songs and stories of the South with the Evelyn Pittman Choir as the headliner. The latter venture, initially aired as a 31-episode cycle during 1941-42 was offered as a syndicated version the following two years and then new scripts were broadcast for a two-month session during 1944. While at WKY, Bishop also contributed to Lights Out, Big Town and Columbia Workshop. His accomplishments earned him an invitation to join the New York staff of the Blue Network. Though he declined this particular offer, he wrote the black magic thriller The Strange Stories of Dr. Karnac, broadcast on that web during the winter and spring of 1943.

Shortly after the final 1944 broadcast of Dark Fantasy, Bishop joined the crew of WKAT in Miami, Florida. The following year Southern Florida audiences tuned in a short-lived series of this program. In January 1948, Bishop attained the program directorship of WKAT’s rival, WIOD. In addition to his station duties, he taught classes in radio.

During the fall of 1950, Bishop’s favorite entity was rekindled once again under the new title Beyond the Veil. This production was a joint effort among WIOD and the Miami Civic Theatre, which had been recently reorganized. The program was often billed as Civic Theatre in newspapers. An episode of this series, “Three Lines of Old French” was adapted from the A. Merritt pulp yarn published in All-Story Weekly (August 9, 1919). This was one of the few occasions in which Bishop transformed the work of another author instead of creating an original story. In addition to Merritt, Bishop was also a fan of Walter B. Gibson. Bishop had the opportunity to meet The Shadow’s pulp creator in Miami during the early 1960s. A letter from Bishop to his former WKY associate Daryl McAllister revealed that Gibson was acquainted with Dark Fantasy. Unfortunately, the letter did not provide any additional details. Dark Fantasy is one of the few radio programs which commenced its life as a network venture and then returned later via local airwaves.

As a complementary endeavor to his practices in dramatics, Bishop initiated The Editor’s Report in 1950, a commentary on current events, society and government on all levels. This was an extremely popular program. Often sponsored, it remained a WIOD fixture into 1958.

In 1967, the long-time executive retired from WIOD but continued his broadcasting career at stations in Michigan. He passed away at age 83 in 1996. Scott Bishop is to be acknowledged for his contributions to the medium especially local drama, which he continued to promote during the 1950s.

There is extant audio of Dark Fantasy and Southern Rivers, but no other programs have surfaced. Thus, this author calls upon fellow admirers of Scott Bishop to seek ‘lost’ recordings (and also scripts). Be forewarned, however, that there are no scripts of The Mysterious Traveler or The Sealed Book bearing his name. Despite what many print and online sources state otherwise, these two programs were the sole creation of Robert Arthur and David Kogan. This author thanks Scott’s daughter Lea Bailey for sharing her father’s correspondence. Author contact khschadow@gmail.com

MartinGrams.biz: The Lone Ranger Rides again

by Martin Grams

Believe it or not, the premiere broadcast date for The Lone Ranger radio program has been a subject of controversy over the decades. The exact broadcast date varies depending on what book or magazine article you read. The reasons for the discrepancy also vary depending on the authors. Some claim the premiere broadcast date was January 30, 1933. Others claim January 31. And yet others claim February 2, 1933. What I personally find amazing is the fact that the correct answer can be found when consulting archival documents but since the primary reason for the discrepancy is because the majority of authors chose to reprint what they find in other prior published reference guides, magazine articles and websites. Preferring to go directly to the source, the answer is, of course, January 31, 1933. The remainder of this article will now go into detail how January 31 was determined, and the origin of those two mistakes that continue to pop up on multiple websites, magazine articles and published reference guides. (So if you want to save yourself five minutes of reading and avoid the nitty-gritty, accept January 31, 1933 and move on. Else, enjoy reading the next few paragraphs…)

To understand the origin of The Lone Ranger one must take into account how most radio programs originated during the 1930s. A sponsor would commission an advertising agency to create a number of proposals and during a meeting between sponsor and account executives, listen to the pitches (often incorporated with artistic interpretations through a slide show on an art easel which today we would refer digitally to as a power point presentation). The pitches would examine how the program would interconnect with the radio listeners, and the sponsor’s product. As an example, an ad agency representing General Mills would have proposed half a dozen children’s serial adventures and one of those proposals would have been Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy, which promoted the hero’s athletic prowess and abilities, combatting villains of all sorts, including the harsh elements of Mother Nature, and thus the commercials would have emphasized how Wheaties was essential to grow strong muscles and bones like their hero, Jack Armstrong.

When James Jewell, director of dramatic programs over radio station WXYZ in Detroit, contacted Fran Striker to write up a series of dramatic westerns, little did he know how historically valuable those letters of communication would become. Striker lived in Buffalo, New York. With respect to the U.S. Post Office, the postal system was more efficient back in the 1930s than it is today. If Jewell mailed a letter to Striker on Wednesday, Striker received the letter on Thursday. If Striker mailed a reply on Friday, Jewell received the letter on Saturday. Because The Lone Ranger radio program was conceived through drafts of multiple radio scripts, and Jewell’s input and Striker’s output was documented through suggestions in the form of letters, the correspondence exchanged between the two have become historical documentation that cannot be refuted.

Fran Striker

Advertising agencies often created multiple proposals, large companies would agree to sponsor said program, and it was the duty of the ad agencies to hire producers, directors, script writers, and actors, and lease airtime from the networks. Therefore networks like NBC and CBS would leave airtime to the ad agencies, who were also responsible for writing “copy,” i.e. the commercial breaks pitching the product. In short, the networks provided the studio and the microphones. The advertising agencies assembled the rest. The sponsors were billed once a month for the coverage spanning multiple radio stations coast-to-coast.

Advertising agencies, like major companies, were bought and sold over the years so much of their historical documentation has been tossed into the dumpster. Worse, little exists from radio proposals during sponsor-agency conferences, especially since inter-office memos rarely exist even if corporation paperwork survives. So the fact that Jewell and Striker corresponded back and forth is extremely rare in the history of radio broadcasting and we are extremely lucky to have those historical documents to consult.

Amongst the multiple letters exchanged between Jewell and Striker beginning in late December 1932 was a letter dated January 21, 1933, in which Striker was advised that the new show would start the following Monday, January 30, 1933. The same letter made a few suggestions with the following notations: “I am going to start The Lone Ranger series Monday, the 30th and I am herein including the few suggestions I spoke of in my last letter. If it is humanly possible, I would like to have six more of these scripts by that time. I am going to use script No. 2 as the opening bill because I feel that it is more characteristic of the type of story we will want to use… I hope the above suggestions won’t cramp your style. I realize they have changed the character you have created… but only in a minor way… We’ll keep you posted on the listeners’ interest created by the new series so you can use same for publicity.”

Jewell’s reference to an “opening bill” was the broadcast of February 2, 1933, promoted in the Detroit Evening Times on the same morning: “Out in the wide-open spaces, where men are not crooners and women are radio actresses, where fast riding and quick shooting are the best arguments. Yes sir, that’s the location of the operations of the unique character ‘The Lone Ranger’ who makes his bow in a new dramatization series to be heard three times weekly on WXYZ starting at 9:00 p.m. today. Through his daring, his riding and his shooting, this mystery rider won the respect of the entire West – the west of the Old Days, where every man carried his heart on his sleeve and only the fittest remained to make history for the Golden States. Though The Lone Ranger was known in seven states, he earned his greatest reputation in Texas. None know from where he came and none knew where he went. A fiery horse, with the speed of light, a cloud of dust, a hearty laugh – mystery, suspense, drama, and above all, Mr. Dennis, purity and no naughty words.”

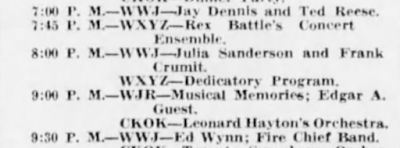

While the premiere was planned for Monday, January 30, the program would be pushed forward to Tuesday, January 31, as part of the station’s 90-minute dedicatory program. A letter dated January 26 from Jewell, informing Striker of the new date, confirms this. Newspaper listings verify the station’s dedicatory program for the evening of January 31. Even a photo and caption in a Detroit newspaper remarked, “Listen for the Lone Ranger on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday nights.”

So, with January 31 proven conclusively to be the premiere date, the question remains: why do some people continue to claim the premiere was January 30, while others claim February 2? Over the years, George W. Trendle, Raymond Meurer, newspapers and magazine articles and even the 20th anniversary broadcast of The Lone Ranger (January 30, 1953) made reference to the January 30 date. The Michigan Radio Network was launched on January 30, but the dedicatory program aired on the evening of January 31. Fixation on the date of the network’s official founding is the reason why such a major blunder over the years can be explained.

So, with January 31 proven conclusively to be the premiere date, the question remains: why do some people continue to claim the premiere was January 30, while others claim February 2? Over the years, George W. Trendle, Raymond Meurer, newspapers and magazine articles and even the 20th anniversary broadcast of The Lone Ranger (January 30, 1953) made reference to the January 30 date. The Michigan Radio Network was launched on January 30, but the dedicatory program aired on the evening of January 31. Fixation on the date of the network’s official founding is the reason why such a major blunder over the years can be explained.

The dedicatory program on the evening of January 31, 1933, was promoted to potential sponsors through the mail, in the hope that a number of regional companies would bankroll some of the proposed programs… including The Lone Ranger. “There had been no publicity preceding the first broadcast,” Meurer wrote, referring to the dry run. The first mention of the new program appeared in the Detroit Evening Times on February 2, 1933. It was this advertisement, proudly hailing the program’s premiere, that caused some historians to mistake the premiere date of The Lone Ranger as February 2, 1933. Conspiracy theorists might want to debate that February 2 should be considered the premiere of The Lone Ranger, and dismiss any on-air dry run, but the radio scripts were officially numbered and the February 2 radio script is labeled “Script #2.” Succeeding radio scripts featured consecutive sequential numbering.

In December 1938, when the radio program featured a week-long celebration for the radio program’s fifth anniversary, the cast and crew dramatized the very first Lone Ranger radio adventure, harkening back not to the February 2 radio script, but the January 31… the script labeled “Script #1.”

To add more conclusive evidence, court documents between The Lone Ranger, Inc. vd. Earl W. Curry and “Jack” Smith, dated October 2, 1947, attested the January 31, 1933, premiere date.

So there you have it. January 31, 1933 was the premiere broadcast date of radio’s The Lone Ranger. Scans of the documents referenced above, among other historical documents, can be found in the book The Lone Ranger: The Early Years, 1933-1937, available at www.martingrams.biz

Hollywood 360 Schedule

6/5/21

The Adv. of Sherlock Holmes 11/9/46 The Singular Adventure of the Dying Schoolboys

Duffy’s Tavern 4/6/49 Archie and Finnegan Double-Date

Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch 1950s Jeff Ross is Murdered

The Line Up 4/8/52 The Cornered Cop Killer Case

Philo Vance, Detective 1/4/49 The Magic Murder Case

6/12/21

The Whistler 7/7/48 Fatal Appointment

The Burns & Allen Show 12/12/44 w/ guest, Frank Sinatra

Barrie Craig, Confidential Investigator 3/1/53 Behold a Corpse

Our Miss Brooks 2/13/49 Stretch Must Pass English

Murder By Experts 8/15/49 Dig Your Own Grave

6/19/21

X Minus One 5/8/56 The Seventh Order

Fibber McGee & Molly 10/19/48 Portable Radio at Repair Shop

Gunsmoke 11/11/56 Pretty Mama

The Adv. of Philip Marlowe 4/16/49 The Heat Wave

The Columbia Workshop 4/21/46 The Playroom

6/26/21

Box Thirteen 1/9/48 Damsel in Distress

The Martin & Lewis Show 10/7/52 w/ guest, Jane Wyman

Inner Sanctum Mystery 11/6/45 The Wailing Wall

Frontier Gentleman 8/17/58 Wonder Boy

Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar 5/10/59 The Fatal Fillet Matter

© 2021 Hollywood 360 Newsletter. The articles in the Hollywood 360 Newsletter are copyrighted and held by their respective authors.