NEWSLETTER | VOL. 14, June 2022

Welcome to this month’s edition of The Hollywood 360 Newsletter, your place to get all the news on upcoming shows, schedule and interesting facts from your H360 team!

Carl’s Corner

by Carl Amari

Hello everyone – here’s the Hollywood 360 Newsletter, June 2022 / Vol. 14. As someone on our mailing list, you’ll receive the most current newsletter via email on the first day of every month. If you don’t receive it by the end of the first day of the month, check your spam folder as they often end up there. If it is not in your regular email box or in your spam folder, contact me at carlpamari@gmail.com and I’ll forward you a copy. The monthly Hollywood 360 newsletter contains articles from my team and the full month’s detailed schedule of classic radio shows that we will be airing on Hollywood 360. Each month I’ll write an article on one of the classic radio shows we’ll present on Hollywood 360. The week of June 11th, 2022 we’ll be airing an episode of The Black Museum starring Orson Welles so here’s an article on this wonderful true-crime series. Enjoy!

Hello everyone – here’s the Hollywood 360 Newsletter, June 2022 / Vol. 14. As someone on our mailing list, you’ll receive the most current newsletter via email on the first day of every month. If you don’t receive it by the end of the first day of the month, check your spam folder as they often end up there. If it is not in your regular email box or in your spam folder, contact me at carlpamari@gmail.com and I’ll forward you a copy. The monthly Hollywood 360 newsletter contains articles from my team and the full month’s detailed schedule of classic radio shows that we will be airing on Hollywood 360. Each month I’ll write an article on one of the classic radio shows we’ll present on Hollywood 360. The week of June 11th, 2022 we’ll be airing an episode of The Black Museum starring Orson Welles so here’s an article on this wonderful true-crime series. Enjoy!

The Black Museum

By Carl Amari and Martin Grams

Produced in the UK and starring Orson Welles, The Black Museum specialized in recreating colorful true murder cases taken from the annals of Scotland Yard. At the real Black Museum, located at the Metropolitan Police headquarters in London, artifacts from famous criminal trials are displayed. These curious and sometimes gory relics – a yellowed tooth, a battered trunk, a blood-stained knife – gave Welles the opportunity to dramatize the murder cases in which they played vital roles. The series, which emphasized crime-solving techniques, offered American listeners the chance to observe how British “Coppers” tracked down culprits. Released through MGM Radio Attractions and broadcast over Mutual, the series eventually gained a sponsor, General Mills. NBC was initially approached by the producer, Harry Alan Towers, but decided to create its own in-house version, Whitehall 1212 – the phone number of Scotland Yard. Wyllis Cooper, the writer and director of the NBC series, beat Mutual to the punch and Whitehall 1212 went on air two months before The Black Museum. For a period of six months, radio listeners could hear two semi-documentary murder stories from the case files of Scotland Yard, on two separate networks. Gripping and well-paced, The Black Museum outranked its competitor, with its horror value upped by Welles’ portentous narration, which bridged the plot sequences. Recording the program in the UK, with British actors playing all the roles also gave authenticity to the dramatizations of crimes that took place abroad. Producer Harry Alan Towers maintained a high level of consistency and quality throughout the series, and the venture was profitable enough for him to convince Welles to star in another radio vehicle, The Lives of Harry Lime.

LEND ME YOUR EARS | THIS MONTH’S SONG: THE DEVIL WENT DOWN TO GEORGIA by The Charlie Daniels Band, RELEASED: 1979

by Lisa Wolf

“We had rehearsed, written, and recorded the music for our Million Mile Reflections album, and all of the sudden we said, ‘We don’t have a fiddle song. I don’t know why we didn’t discover that, but we went out and we took a couple of days’ break from the recording studio, went into a rehearsal studio, I just had this idea: The devil went down to Georgia.” ~ Charlie Daniels

Charlie Daniels’ “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” is one of the greatest story -telling songs, with lyrics that tell of a fiddler’s confrontation with Satan. The song was a #1 hit on the Country chart, but also crossed over to the pop chart, climbing to #3 on the Hot 100. This song won the 1979 Grammy for Best Country Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal.

Charlie Daniels’ “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” is one of the greatest story -telling songs, with lyrics that tell of a fiddler’s confrontation with Satan. The song was a #1 hit on the Country chart, but also crossed over to the pop chart, climbing to #3 on the Hot 100. This song won the 1979 Grammy for Best Country Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal.

Channeling his his life story, Daniels came up with a contest. “I wrote a lyric about a kid named Johnny who was a great fiddler. But I needed something more exciting than an ordinary contest. The stakes had to be higher. So I had the Devil go down to Georgia to challenge Johnny. If Johnny won, he’d get the Devil’s gold fiddle. But if he lost, the Devil would get his soul. Johnny accepts the challenge.”

Charlie Daniels was inducted into the Grand Ol’ Opry in 2008 and the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2016. He released his last album, Beau Weevils — Songs in the Key of E, in 2018, before passing away July 6, 2020.

A sequel to the song, titled “The Devil Comes Back to Georgia”, was recorded by Daniels and fiddle player Mark O’Connor in 1993, featuring guest performances by Travis Tritt (as the devil), Marty Stuart (as Johnny) and Johnny Cash as the narrator. In the sequel, the now-adult Johnny is married and has a child. Hoping to take advantage of Johnny’s sinful pride, the Devil challenges him to a rematch

Looking Back at the Future of Dimension X and X Minus One

By Barry Richert

It was a glorious time to be a science fiction fan. Movie screens were filled with gleaming silver rockets launching into space and defenseless earthlings being terrorized by invading bug-eyed monsters (or BEMs as those “in the know” called them). On  newsstands, magazines like Astounding, Galaxy, and Orbit were showcasing provocative tales of the future from up-and-coming genre writers. Even television had gotten into the act with Captain Video and His Video Rangers. It was the 1950s, and the science fiction boom was exploding out of a growing fascination with nuclear power, paranoia about the Cold War, and the allure of space exploration technology.

newsstands, magazines like Astounding, Galaxy, and Orbit were showcasing provocative tales of the future from up-and-coming genre writers. Even television had gotten into the act with Captain Video and His Video Rangers. It was the 1950s, and the science fiction boom was exploding out of a growing fascination with nuclear power, paranoia about the Cold War, and the allure of space exploration technology.

Not to be outdone, radio—with its ability to let the listener’s imagination provide the special effects—proved itself to be the ideal medium for science fiction. Two anthology series that launched on NBC during the 1950s are considered by many to represent the apex of audio science fiction: Dimension X and its follow-up, X Minus One. The goal of these programs was to offer a weekly anthology for adults featuring stories written by the hottest science fiction writers in the field.

Dimension X debuted on NBC April 8, 1950, and instantly garnered the acclaim of science fiction fans by dramatizing stories that had formerly been published in Astounding Science Fiction Magazine. The contributing writers were a “who’s who” of science fiction literature: Ray Bradbury, Robert A. Heinlein, Robert Bloch, Murray Leinster, Isaac Asimov, Kurt Vonnegut, and numerous others. Ernest Kinoy—who would go on to write the TV movies Victory at Entebbe and Skokie, as well as an Emmy-winning episode of the miniseries Roots—adapted the stories with George Lefferts, who would later create and write the series Rocky Fortune and produce the daytime TV drama Ryan’s Hope.

Each week narrator Norman Rose announced that we’d be hearing “Adventures in time and space, told in future tense.” A typical sampling of the storylines shows the diversity of themes explored:

Each week narrator Norman Rose announced that we’d be hearing “Adventures in time and space, told in future tense.” A typical sampling of the storylines shows the diversity of themes explored:

- Nightfall by Isaac Asimov – The population of a planet that only experiences night once every several thousand years must confront madness and the breakdown of civilization as sunset approaches.

- There Will Come Soft Rains by Ray Bradbury – After a nuclear blast kills a family, their automated house dutifully continues to perform its regular tasks, but finds that death may not be reserved exclusively for humanity when disaster strikes.

- The Professor Was a Thief by L. Ron Hubbard – When Grant’s Tomb disappears, a mild-mannered professor insists he is responsible. Everyone laughs at his claim, until the Empire State Building vanishes.

Dimension X was an inexpensive program for NBC to produce. Network staff already under contract were employed on the show, which helped keep the budget down to roughly one-sixth of the average half-hour radio program. Albert Buhrman composed the music, often making use of the theremin, an electronic musical instrument which lent an eerie, futuristic ambience to the otherworldly tales. The show was broadcast live for the first 13 weeks, after which all remaining episodes were prerecorded. Fifty episodes were aired before Dimension X ended on September 29, 1951.

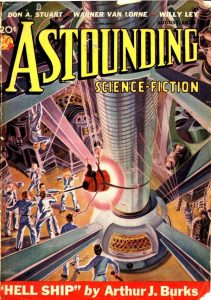

Originally intended as a Dimension X revival, X Minus One debuted four years later on April 24, 1955. The first 15 episodes were remakes of Dimension X stories, but original scripts were produced for the remainder of the series. Once again, the program partnered with a popular science fiction publication—Astounding Science Fiction and later, Galaxy Science Fiction—to provide content. Ernest Kinoy and George Lefferts returned to do most of the scriptwriting and adapting, along with new writers Howard Rodman, who went on to write for the TV series Naked City and Route 66 and became an associate producer on Peyton Place, and William Welch, whose writing credits would later include Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space, and The Time Tunnel.

Announcer Fred Collins’ opening narration set the tone for each episode: “From the far horizons of the unknown come transcribed tales of new dimensions in time and space. These are stories of the future; adventures in which you’ll live in a million could-be years on a thousand may-be worlds.” X Minus One examined such themes as the perils of technology, mankind’s immeasurable capacity for bigotry, and the fear of scientific progress. Some of the more acclaimed episodes included…

- Cold Equations by Tom Godwin – A woman stows away aboard a medical spaceship to see her husband on the destination planet. When the pilot informs her there is not enough fuel to land with her additional weight, she is faced with two tragic choices: a) stay on the ship and let sixteen men die, including her husband, or b) leave the ship and die herself.

- Sam, This is You by Murray Leinster – A telephone repairman gets a phone call providing the solution to his girlfriend problems. The catch? The call is from himself, one week in the future.

- Universe by Robert A. Heinlein – A gigantic ark has been floating in space for generations carrying two civilizations, humans in the lower half and mutants in the upper half. When one of the humans explores the upper half of the ship, he is forced to reconsider humanity’s propensity for discrimination—which then leads him to question what lies outside the ark.X Minus One entered the record books as the longest-running science fiction radio series in history. After three years and 126 episodes, the show was canceled, airing its last episode on January 9, 1958.As television overtook radio in popularity, many believed that science fiction radio drama had breathed its last. In the 1970s, however, a new episode of X Minus One was produced: The Iron Chancellor by Robert Silverberg. Little information is available about this attempted revival, except that it aired on the NBC radio network on January 27, 1973, and that no further episodes were created. NBC decided to rebroadcast the original 1950s series the same year, but intermittent scheduling coupled with recurring pre-emptions led to the end of its run on March 22, 1975.Fortunately, the spirit of Dimension X and X Minus One lived on throughout the 1970s and 1980s in the form of radio dramas like the Rod Serling-hosted The Zero Hour (1973-1974), the syndicated Alien Worlds (1979-1980), and NPR’s Bradbury 13 (1983-1984). Today, podcasts have become the home of audio drama, with science fiction emerging as one of the most popular genres. Although the golden age of radio is long past, Dimension X and X Minus One continue to inspire creative minds to dream up compelling audio drama by looking to the future.

Moonlighting and Television Noir

by Karl Schadow

The noir theme continues this month as the focus turns from radio to the small screen. Though there were several excellent noir-themed programs of the 1940s and 1950s including Martin Kane, Private Eye and Meet McGraw, the subject of this article is culled from the 1980s. It is “The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice” from the series Moonlighting (1985 – 1989). The episode’s titillating title, a tip-of-the-hat to the James M. Cain novel and subsequent films, “The Postman Always Rings Twice” forecasts a special presentation. It was originally telecast October 15, 1985.

Moonlighting was created by Glenn Gordon Caron who developed the series as a satire on the current plethora of detective shows. The program, the first successful dramedy, starred Cybill Shepherd and Bruce Willis as owner Maddie Hayes and snarky employee David Addison, respectively, of The Blue Moon detective agency. Written by Debra Frank and Carl Sautter, and directed by Peter Werner, “The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice” was introduced by Orson Welles who alerts viewers that their television screens will turn, in a few minutes, to black and white. Why?

Moonlighting was created by Glenn Gordon Caron who developed the series as a satire on the current plethora of detective shows. The program, the first successful dramedy, starred Cybill Shepherd and Bruce Willis as owner Maddie Hayes and snarky employee David Addison, respectively, of The Blue Moon detective agency. Written by Debra Frank and Carl Sautter, and directed by Peter Werner, “The Dream Sequence Always Rings Twice” was introduced by Orson Welles who alerts viewers that their television screens will turn, in a few minutes, to black and white. Why?

The usual color action opens with Maddie and David delivering some unwanted news to their client whose wife has been shockingly faithful. With any potential divorce settlement now out of the picture, the client decides not to purchase the Flamingo Cove, a former posh theater that has seen better days. Interestingly, the duo from The Blue Moon learns from the theater’s current owner of an incident that occurred there during the 1940s involving a love triangle in which the husband of a big band’s vocalist was murdered. But who was the guilty party, the wife or her lover? In the car on the way back to their office, Maddie and David engage in the show’s classic banter with each taking a different side in the case. Upon returning to their respective domiciles, each dreams of their version of that notorious event.

In order to achieve the atmosphere of the genre, the dream sequences were shot in black and white. This was a daunting task for cinematographer Gerald Perry Finnerman as he had no prior experience with black and white television. In an Archive of American Television interview, he related that one dream was to be of the “glossy, M-G-M type” while the other was slated “a seedy, down look.” He also provided details on special lighting features and also the necessity of working closely with the art director, makeup artist and costume designer so that the final result would be satisfactory. The sequences were filmed at the former Aquarius Theatre on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood.

Another aspect of this intriguing Moonlighting episode was the music composed and conducted by Alf Clausen. In an Archive of American Television interview, he noted the preference for the big band style of that period. Cybill Shepherd’s renditions of both Blue Moon and I Told Ya I Loved Ya, Now Get out were superb. Having no previous experience on cornet and after being expertly coached, Bruce Willis did yeoman’s work with the instrument, though the actual sound was dubbed over. One memorable scene has a shirtless Willis playing his horn next to a windowsill with a neon sign as a backdrop.

The episode deservedly earned both Directors Guild and Primetime Emmy Award Nominations. It was an excellent example of the ingenuity of the cast and crew in paying a tribute to the noir genre.

Contact author at khschadow@gmail.com

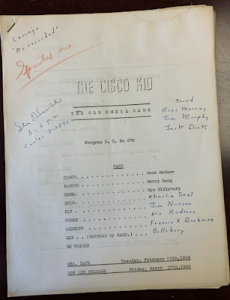

MartinGrams.biz: THE CISCO KID: Casting Discoveries

by Martin Grams

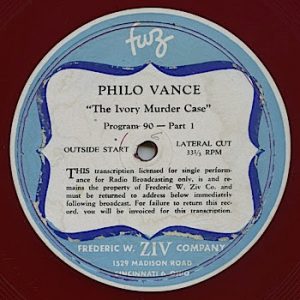

It was the afternoon of May 14, 1947, that six of the nation’s top children’s programs were hit with a boycott instituted by the Lafayette District, P.T.A., in San Francisco. Membership of 318 pledged itself to tune out programs such as Tennessee Jed, Hop Harrigan, Sky King, Tom Mix, The Lone Ranger and The Cisco Kid. This was among the earliest (if not first) recorded action taken by a parent group to curtail the activities of network or local programs which, they claimed, was teaching “nothing but death and violence.” Their efforts were short-lived, however, as The Cisco Kid (along with his contemporaries) continued to ride the airwaves from coast-to-coast. If anything, The Cisco Kid was due for vast expansion courtesy of Frederic W. Ziv and his transcription empire.

It was the afternoon of May 14, 1947, that six of the nation’s top children’s programs were hit with a boycott instituted by the Lafayette District, P.T.A., in San Francisco. Membership of 318 pledged itself to tune out programs such as Tennessee Jed, Hop Harrigan, Sky King, Tom Mix, The Lone Ranger and The Cisco Kid. This was among the earliest (if not first) recorded action taken by a parent group to curtail the activities of network or local programs which, they claimed, was teaching “nothing but death and violence.” Their efforts were short-lived, however, as The Cisco Kid (along with his contemporaries) continued to ride the airwaves from coast-to-coast. If anything, The Cisco Kid was due for vast expansion courtesy of Frederic W. Ziv and his transcription empire.

Jack Mather (left) and Harry Lang (right)

The history of radio’s Cisco Kid program began on the evening of October 2, 1942, when Mutual premiered a weekly primetime rendition of the motion picture caballero. Under the direction of Alvin Flanagan, the hero romanced women as suave a reputation as Cesar Romero established on the big screen. Sponsorship entitlement of time slots would result in The Cisco Kid program bouncing back and forth at various time slots in two-month increments, Friday and Tuesday evenings, settling for an eight-month position on Saturday evening through 1944. Executives at Mutual believed the program had potential to gain a sponsor, as a result of the on-going motion pictures that were being produced in Hollywood.

Frederic W. Ziv and John Sinn, having purchased the radio rights, licensed the series for broadcast over the Mutual Broadcasting System. The program originated out of New York City with Jackson Beck in the title role. In July of 1943, days after the radio program went off the air for a few months (it would return in October 1943), Ziv and Sinn sat down with Phil Krasne and James Burkett, producer of the Cisco Kid movies at Monogram Studios, to work out and coordinate a plan whereby both the weekly radio program and the motion pictures cross-promote each other. By November screen tests were being made to find an actor who could play the role both on radio and in the movies concurrently. (It would take a few years for that to happen, but we cannot blame them for trying in 1943.)

The weekly prime-time program concluded on the evening of February 24, 1945. While it looked as if the series would not return to radio, Ziv never gave up hope. One year later, a major shake-up at Mutual created a vacancy. George W. Trendle sold his Michigan Radio Network to ABC and the network gained an exclusive: The Lone Ranger. Up until then The Lone Ranger program aired over the Don Lee Network three days a week. The shift to ABC meant The Lone Ranger would no longer air over KHJ in Los Angeles. Frederic W. Ziv agreed to license The Cisco Kid as a substitute for The Lone Ranger, which would air three-times-a-week. Children in Los Angeles who wanted to hear The Lone Ranger simply had to change to KECA and listen to their program at 6 p.m., while The Cisco Kid aired over KHJ at 6:30 p.m.

The weekly prime-time program concluded on the evening of February 24, 1945. While it looked as if the series would not return to radio, Ziv never gave up hope. One year later, a major shake-up at Mutual created a vacancy. George W. Trendle sold his Michigan Radio Network to ABC and the network gained an exclusive: The Lone Ranger. Up until then The Lone Ranger program aired over the Don Lee Network three days a week. The shift to ABC meant The Lone Ranger would no longer air over KHJ in Los Angeles. Frederic W. Ziv agreed to license The Cisco Kid as a substitute for The Lone Ranger, which would air three-times-a-week. Children in Los Angeles who wanted to hear The Lone Ranger simply had to change to KECA and listen to their program at 6 p.m., while The Cisco Kid aired over KHJ at 6:30 p.m.

For the new three-times-a-week rendition, which premiered on Monday, February 25, 1946, Jack Mather and Harry Lang were hired to play the leads. The program was tamed to fit a format best suited for children. Romance between The Cisco Kid and the damsel in distress was tamed down; Pancho became more of a comedic sidekick. Intercontinental Bakeries, makers of Weber Bread, sponsored the new rendition. While the program aired three times more frequent than the prior Mutual rendition, The Cisco Kid aired regionally (not nationally)  over KHJ in Los Angeles, while The Lone Ranger continued to air nationwide from coast-to-coast over ABC.

over KHJ in Los Angeles, while The Lone Ranger continued to air nationwide from coast-to-coast over ABC.

Beginning with the broadcast of Monday, January 10, 1949, Paul Pierce was hired to direct the program and ZIV funded the recording of each and every broadcast that followed. ZIV had intentions of syndicating the series via transcription disc. Initially the broadcasts were recorded as they aired live, with the Weber Bread commercials deleted out afterwards. For syndication purposes, the programs needed to run a span of 25 minutes for syndication, allowing for local announcers to deliver the sponsor’s message. Within a few weeks, by March, it was decided that the assignment would be easier if the radio adventures were recorded in advance without the commercials. For the KHJ broadcasts, Weber commercials would be delivered live just as the syndicated renditions across the country.

For a brief summary of the above: The Cisco Kid was broadcast as a weekly program from October 2, 1942, to February 14, 1945. Beginning February 25, 1946, The Cisco Kid aired three days a week over KHJ in Los Angeles. Two years later the radio broadcasts were recorded for syndication.

Two radio broadcasts pre-syndication era, “The Cisco Kid Meets His Sister” (December 11, 1942) and “A Ghost for the Cisco Kid” (May 13, 1944) exist in recorded form. The remainder of the recordings that circulate today in collector hands (over 300 at present count) are from the Frederic W. Ziv syndication. For the record, all 792 of the ZIV syndications exist in recorded form even though more than half are not circulating yet. For collectors of old-time radio programs, any recording of The Cisco Kid radio program pre-dating January 1949 should be considered rare and a true find.

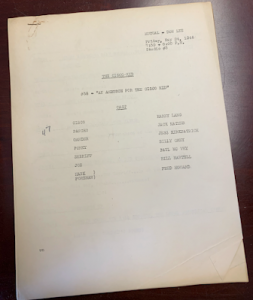

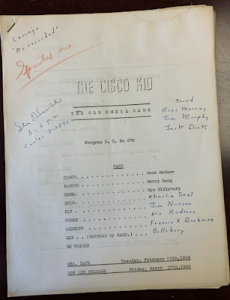

Recently, most of The Cisco Kid radio scripts have been digitized and careful review of those digitized led to a number of discoveries.

The first discovery (and not much of a surprise) is the fact that collectors have been assigning a broadcast date for the syndicated episodes. Syndication meant the series aired at various days and time slots across the country, in regional areas each with different sponsors, which makes assigning a broadcast date futile. However, The Cisco Kid can be one of the exceptions since the radio scripts do feature a “Recording Date” and since those episodes were first heard over KHJ in Los Angeles before they aired across the country through syndication, if any airdates should be assigned, the KHJ broadcasts make more sense. (Many of the radio scripts also include the KHJ broadcast date on top of the recording date.) Thus syndication disc #1 would be dated January 10, 1949, #2 would be dated January 12, #3 would be dated January 14, #4 would be dated January 17, 1949, and so on.

Every broadcast included an official episode number and a script title. Back in the 1980s and 1990s it was common for collectors to create “collector titles,” adding confusion to collectors who discovered they had duplicate recordings with alternate titles.

But perhaps the biggest find was the cast, documented on the cover of each and every radio script. Actors who were well-established on radio played multiple roles on the program including Parley Baer, Tom Holland, Jane Webb, Virginia Gregg, Lillian Buyeff, Parley Baer, Herb Butterfield, John Dehner, Ge Ge Pearson, Peggy Webber, Tim Graham, Ralph Moody, Alan Reed, Rye Billsbury, Vic Perrin, Ralph Moody, Charlie Lung, Jay Novello, Joan Banks, Byron Kane, Lou Krugman, Howard McNear, Jack Petruzzi, Jeanne Bates, Peggy Webber, Herb Ellis, Marvin Miller, and Barney Phillips.

Because the announcer never delivered acknowledgement of the supporting cast at the close of the programs, the extant radio scripts provides us with a number of surprises. Silent screen star Francis X. Bushman, who went off to Chicago in the early thirties to try his hand at a radio career, returned to Hollywood during the 1940s and his name appeared on no less than 49 episodes of The Cisco Kid. Silent screen actress Ynez Seabury, whose career was under the direction of D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille, played the role of Annie in “Arms for the Cisco Kid” (episode #48) and as Betty and Ma Grimstead in “An Execution for the Cisco Kid” (episode #52). Silent screen actress Betty Blythe, best remembered today for her exotic roles in such films as The Queen of Sheba (1921) and her starring portrayal of H. Rider Haggard’s She (1925), appeared in four episodes of The Cisco Kid, listed below:

(as Maude) “Murder at Massacre Junction” #401

(as Sadie) “The Lady of Six-Gun Café” #425

(as the Duchess) “The Duchess of San Antonio” #451

(as Cora) “War Drums” #562

Radio actress June Foray, best known for supplying voices for cartoon characters including Rocky the Flying Squirrel and Cindy Lou Who, played supporting roles in four episodes:

(as Amelia) “A Cape for the Cisco Kid” #11

(as Frances) “Four Aces for the Cisco Kid” #45

(as Betsy) “Senorita Pancho and the Cisco Kid” #63

(as Hazel) “Slaves for the Cisco Kid” #103

An obscure comedian/character actor named Billy “Buddy” Grey (sometimes spelled Gray) who worked on radio in the 1940s and began in San Francisco as a sidekick to comic Jack Kirkwood, played supporting roles on seven episodes:

(as Reardon) “A War for the Cisco Kid” #14

(as Yancey) “Handcuffs for the Cisco Kid” #29

(as Boots and Ed) “A Tax for the Cisco Kid” #30

(as Porky) “An Ambush for the Cisco Kid” #38

(as Sheriff Grimstead) “An Execution for the Cisco Kid” #52

(as Frank) “A Lion for the Cisco Kid” #50

(as Coker) “A Dead End for the Cisco Kid” #55

Actor Jeff Chandler appeared in two episodes, under the name of Ira Grossel (his birth name). Chandler did a lot of radio in the 1940s, including playing the title role of Michael Shayne. After signing a lucrative contract with 20th Century Fox, Chandler was granted permission to continue doing radio as long as he was billed “Ira Grossel” instead of “Jeff Chandler,” except when the movie studios wanted to highlight one of his up-coming movie appearances. In a 1951 interview with Hedda Hopper, Chandler remarked how he enjoyed performing for radio more than movies, citing radio actors “have to make their roles come alive, and they only have their voices with which to do it, but in pictures, the technique is quite different. The actor is only a small part of the performance. He lends his intelligence and personality to the role, but the greatest part of the performance belongs to the producer, who puts him in a certain type of part; the director, who tells him how to play it; and the cutter, who edits what’s done. That’s why I find being a movie actor not particularly gratifying.” While his name was not credited on the air, his name is listed as “Ira Grossel” on the cover of two scripts: as Bill in “A Rescue for the Cisco Kid” (#43) and as Jim in “An Arrest for the Cisco Kid” (#66).

Names also discovered among the cast of The Cisco Kid radio programs was actor Pinky Parker, who appeared in a dozen episodes, and actress Louise Arthur. Stephen Chase, the actor best known for playing a doctor in When Worlds Collide (1951) and the iconic scene in The Blob (1958), played supporting roles in 13 episodes. Of those 13, the following presently exist in collector hands: “Return of the Laughing Bandit” (#178), “The Bull-Whacker” (#222), “Murder at Red Clay Bend” (#276), “Gold in the Conestoga” (#288) and “The Mystery of Nine Mile Mesa” (#291).

Names also discovered among the cast of The Cisco Kid radio programs was actor Pinky Parker, who appeared in a dozen episodes, and actress Louise Arthur. Stephen Chase, the actor best known for playing a doctor in When Worlds Collide (1951) and the iconic scene in The Blob (1958), played supporting roles in 13 episodes. Of those 13, the following presently exist in collector hands: “Return of the Laughing Bandit” (#178), “The Bull-Whacker” (#222), “Murder at Red Clay Bend” (#276), “Gold in the Conestoga” (#288) and “The Mystery of Nine Mile Mesa” (#291).

Don Harvey, who would later play the recurring character of Collins on television’s Rawhide, can be heard in episode #320, “Killer’s Bullets at Chicken Creek.” Mark Lawrence, best known for playing tough guys in B-mysteries and film noir on the big screen, played a role in episode #70, “Gun for Hire.” Elizabeth Harrower, known for playing the recurring role of Miss Perkins, the schoolteacher, on television’s Dennis the Menace, played the female lead in the same episode (“Gun for Hire”) and in episode #115 titled “Stampede.” Frank Lovejoy, before building up star status on radio for such programs as Night Beat on NBC radio (1950-1952), and guest star billing on such programs as Suspense, appears in two episodes of The Cisco Kid: “The Prophet of Boot Hill” (#101) and “Trail of the Iron Horse” (#140). Roscoe Ates, best known as Soapy Jones, the sidekick to cowboy star Eddie Dean in a series of silver screen Westerns from 1946 to 1948, plays supporting roles in two episodes of The Cisco Kid: “His Honor, the Killer” (#126) and “The Lady Sheriff of Sandy Gulch” (#165).

Actress Julie Bennett, who played supporting roles on thousands of radio broadcasts and later made a living providing voices for animated cartoons (including Cindy Bear on The New Yogi Bear Show), appeared in half a dozen episodes. She played the recurring character of “Julie” in the following three episodes: “Stage to Silver City” (#602), “Laramie Land Grab” (#624) and “Outlaw Justice” (#636). Radio announcer Art Gilmore, later to be narrator on television’s Highway Patrol and Mackenzie’s Raiders, played supporting roles on almost a dozen episodes including: “The Fighting Mountain Man” (#540), “The Trouble Makers” (#549), and “The Hurricane” (#559).

Actor Richard Boone, who would later become a household name as Paladin on television’s Have Gun-Will Travel, also acted on radio. He can be heard on such broadcasts as Dragnet, Suspense, Escape and Dangerous Assignment. In The Cisco Kid episode titled “The Vanished Ones” #588, he played the role of Heinrich. Bill Johnstone, radio actor best known as Lamont Cranston, alias “The Shadow” on radio during the early 1940s, appeared in two episodes: as Otto in “The Corpse Maker” (#661), and as Turk in “House of Gold” (#696).

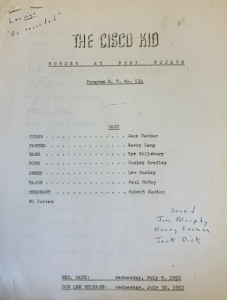

Curley Bradley, best known for playing the role of Tom Mix on the long-running radio program, played supporting roles in nine episodes of The Cisco Kid.

(as the sheriff) “Mule Team Murder” #457

(as Harley) “Judge Colt’s Law” #490

(as Coke) “Gamblers! Gunmen! And Gold!” #506

(as Mike) “Murder at Fort Mojave” #514

(as Sid) “The Mystery of Desolation Canyon” #542

(as Bob) “Law of the Panhandle” #556

(as Boone) “The Lady From Lubbock” #574

(as Charley) “Cashiel Raynor’s Revenge” #598

(as Randy Wolfe) “Killer in the Jail House” #637

Willard Waterman, best known for the role of Throckmorton P. Gildersleeve on The Great Gildersleeveon both radio and television, played supporting roles in ten episodes. Six of those ten exist in collector hands in case anyone wants to listen to them: “The Buffalo Skinner” (#131), “The Gila Stallion” (#146), “Cisco Takes the Trail” (#162), “Avalanche in Arrow Pass” (#177), “The Hermit of Ghost Town Three” (#186), and “Stampede on the Chisolm Trail” (#241).

Willard Waterman, best known for the role of Throckmorton P. Gildersleeve on The Great Gildersleeveon both radio and television, played supporting roles in ten episodes. Six of those ten exist in collector hands in case anyone wants to listen to them: “The Buffalo Skinner” (#131), “The Gila Stallion” (#146), “Cisco Takes the Trail” (#162), “Avalanche in Arrow Pass” (#177), “The Hermit of Ghost Town Three” (#186), and “Stampede on the Chisolm Trail” (#241).

Perhaps the biggest question that remained unanswered (until now) was which episodes specifically did Mel Blanc play the role of Poncho on The Cisco Kid. Until now encyclopedias and magazine articles only listed his name but never the specifics. According to the radio scripts, Mel Blanc played the role from episodes #582 to 591, and again from #630 to 781. Lou Merrill played the role from #600 to 602. Dick Beals played the role of Panchito from #626 to #630, the last of which he shared an adventure with Poncho, who made a return to the program.

Perhaps the biggest surprise was to discover Mala Powers listed among the cast. The actress who appeared in

Actress Mala Powers

dozens of Westerns and science-fiction movies in the 1950s and became a cultural icon over the years, played hundreds of supporting roles on radio including This is Your FBI, The Lux Radio Theatre, Jeff Regan, Investigator, Stars Over Hollywood and The Adventures of Red Ryder. The majority of her radio credits remain unknown due to a lack of proper documentation. Thanks to the preservation of The Cisco Kid radio scripts, her credits as they appear on The Cisco Kid are now fully documented and listed below.

(as Sarah) “Beyond the Frontier” #336

(as Martha) “A Lesson for Billy Jewell” #346

(as Dolly) “To Please a Friend” #358

(as Cleo) “Death by Telegraph” #380

(as Ruth) “Checkerboard of Death” #386

(as Vi) “The Wagon Box War” #404

(as Nora) “The Handsome Bandit” #419

(as Nancy) “The Land Rush” #426

(as Martha) “The Race for Life” #436

(as Lorrie) “The Birthday Party” #444

(as Molly) “Pancho and the Forty Thieves” #459

(as Betty) “Barbed Wire War” #474

(as Ann) “The Courtship of Joe Martin” #515

(as Cassandra) “South of Del Norte” #523

(as Clara) “Pancho and the Princess” #548

(as Betty) “Rodeo” #541

(as Marion) “Convict’s Escape” #557

(as Lola) “Murder at North San Juan” #583

(as Phyllis) “Fight at Devil’s Canyon” #597

(as Agatha Mason) “War in the Pecos Valley” #621

(as Gayle) “Mark of the Eagle” #628

(as Nora Knowles) “Killer in the Jail House” #637

(as Mary) “Blackmail at Roundup” #650

(as Carol) “Treasure of the Aztecs” #664

(as Mary) “Lynch Law” #708

(as Lorna) “The Gunmaker of Texas” #701

(as Lorry, the young girl) “The Gunhawk” #720

(as Nancy) “The Trap” #726

(as Lulu) “Sheriff Longhair” #743

(as Vinnie) “Vengeance of Vinnie Bolton” #758

(as Judy) “Gamble for Life” #768

(as Donna) “The Daughters of Cimarron” #776

When it comes to cast documentation for radio’s The Cisco Kid, and the digitizing of the radio scripts, we should value such discoveries and efforts as it provides a record more accurate than what has been documented elsewhere on the Internet. There are a number of old-time radio fans who listen to recordings and make general assumptions who is in the cast, then contribute their assumptions to websites. (Yes, you read that correctly.) Regrettably, this accounts for hundreds of other radio programs, not just The Cisco Kid, listed on the Internet with incorrect cast details. All of which is a long-winded way of stating that the information contained in this article was taken directly from the radio scripts – no guesswork applied. Personally, I always prefer to go to the source… at least, document from the source.

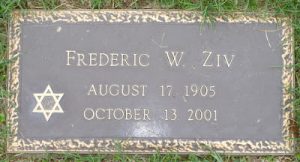

On a positive note, The Cisco Kid is just one of many radio programs in the past year that received some form of preservation and documentation thanks to historians consulting archival materials. Ten years ago, there were a dozen people who would go to the expense traveling to archives, in an effort to properly document old-time radio. Sadly, as of today, that number has dwindled down to two. With so many old-time radio programs that have yet to receive proper documentation, fans of The Cisco Kid can rejoice for extensive treatment about this program (beyond these cast discoveries) will be published in a book in the next year or two, along with other programs produced by Frederic W. Ziv.

P.S. His name is spelled Frederic without a “K.” Verification comes in multiple forms (two reprinted below) so, yes, IMDB and Wikipedia has it incorrect.

Hollywood 360 Schedule

6/4/22 (repeat of 6/12/21 show)

The Whistler 7/7/48 Fatal Appointment

The Burns & Allen Show 12/12/44 w/ guest, Frank Sinatra

Barrie Craig, Confidential Investigator 3/1/53 Behold a Corpse

Our Miss Brooks 2/13/49 Stretch Must Pass English

Murder By Experts 8/15/49 Dig Your Own Grave

6/11/22

The Great Gildersleeve 6/11/44 Future Mother-In-Law Visits

The Black Museum 1952 The Brass Button

Gang Busters 1930s The New York Narcotics Ring

Information Please 8/23/38 Nursery Rhyme

Rocky Jordan 8/7/49 Gold Fever

6/18/22

Box Thirteen 1/16/48 Diamond in the Sky

The Charlie McCarthy Show 11/22/53 w/ guest, Ronald Reagan

Have Gun-Will Travel 2/21/60 That Was No Lady

Nick Carter, Master Detective 4/13/47 The Case of the Chemical Chickens

The Red Skelton Show 5/9/44 Top is Swimming

6/25/22

My Favorite Husband 11/20/48 George Attends a Teenage Dance

The Adv. of the Saint 9/10/50 The Horrible Hamburger

The Big Story 12/6/50 Dictionary and Telephone Lead to a Killer

The Fred Allen Show 2/6/49 w/ guest, Bert Lahr

The Man Called X 3/11/54 The Missing Papers

© 2022 Hollywood 360 Newsletter. The articles in the Hollywood 360 Newsletter are copyrighted and held by their respective authors.