NEWSLETTER | VOL. 23, March 2023

Welcome to this month’s edition of The Hollywood 360 Newsletter, your place to get all the news on upcoming shows, schedule and interesting facts from your H360 team!

Carl’s Corner

by Carl Amari

Hello everyone and happy March! Here’s the Hollywood 360 newsletter, March 2023 / Vol. 23. As someone on our mailing list, you’ll receive the most current newsletter via email on the first day of every month. If you don’t receive it by the end of the first day of the month, check your spam folder as they often end up there. If it is not in your regular email box or in your spam folder, contact me at carlpamari@gmail.com and I’ll forward you a copy. The monthly Hollywood 360 newsletter contains articles from my team and the full month’s detailed schedule of classic radio shows that we will be airing on Hollywood 360. Each month I’ll provide an article on one of the classic radio shows we’ll present on Hollywood 360. This month, we’re airing an episode of My Favorite Husband starring Lucille Ball the week of March 18th, so here’s an article on Lucy and her amazing career. Enjoy!

RADIO LEGEND: Lucille Ball By Carl Amari and Martin Grams

As Lucy Ricardo, she brought a tomboy’s enthusiasm and a scatterbrained quality to the long-running I Love Lucy (1951-61) television program. She was the wacky wife making life difficult for a loving but perpetually irritated husband. It’s ironic when you consider the early stages of her acting career: With ambitions to become an actress, Lucille Ball entered a dramatic school in New York City in 1926, but while her classmate Bette Davis received the raves, Ball was sent home on the grounds that she was “too shy.” This classification might have been the Dumbo feather that motivated her into appearing in comedies such as Look Who’s Laughing (1941), The Fuller Brush Girl (1950) and as a sidekick to the Marx Brothers in Room Service (1938).

When she was 12, Ball was encouraged into show business by her grandfather to entertain his cohorts at the Shriners club. After adopting the stage name Diane Belmont and being fired from several chorus jobs, she retreated to her home in Celoron, New York, where she spent two years battling the crippling effects of rheumatoid arthritis… a handicap she kept secret for most of her life. Returning to New York in the early 1930s, Ball returned to working as a model for Hattie Carnegie while also earning money as a Chesterfield cigarette girl. She soon embarked on a Hollywood career, which at first consisted mostly of walk-ons and bit roles before she was turned into a glamorous Goldwyn showgirl in the Eddie Cantor musical Roman Scandals (1933). Under contract by Columbia, the then-blonde, statuesque actress continued to appear in small roles — most notably as a foil for the Three Stooges in one of their earliest film shorts — before her option was dropped. RKO hired Ball at the urging of producer Pandro S. Berman, who featured her in supporting roles in the Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers films Roberta (1935), Top Hat (1935) and Follow the Fleet (1936).

Working her way up Hollywood’s ladder, in the summer of 1948 she accepted the role of Liz Cooper, a zany housewife who found herself facing comical situations, in the radio comedy My Favorite Husband. In the radio series, Lucille Ball’s husband George Cooper was played by veteran actor, Richard Denning. In 1950, CBS came knocking with the offer to adapt the popular radio program to television. Unable to convince network brass to let her real-life husband Desi Arnaz play her husband on the television series she was given creative control to create her own situation comedy series I Love Lucy. Here, she and Arnaz pioneered the three-camera technique now considered the standard in filming television sitcoms. She also became the first woman to own a television studio, when she headed Desilu Productions.

In 1952, her real-life pregnancy was written into the show although the network objected to the use of the word “pregnant” and instead opted for the word “expectant.” All of her pregnancy episodes were reviewed by a minister, a priest and a rabbi to make sure nothing on screen would be considered offensive. When Lucille Ball gave birth on television to her first child, all of America was glued to the screen. On that evening, I Love Lucy had larger ratings than the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II and President Eisenhower’s inauguration.

Paid $50 a week for her role as a supporting actress in Top Hat (1935), Ball now graduated to $3,500 an episode for I Love Lucy along with part ownership of the mega series. Her next-door neighbor, Jack Benny, often referred to her as “Chesterfield,” after learning that the comedienne was once a spokes model for the cigarette brand. But it wasn’t Benny that taught her how to perform on camera. Lucille Ball credited Buster Keaton as her mentor, remarking: “He taught me most of what I know about timing, how to fall and how to handle props and animals.”

Behind the camera, the relationship between Ball and Arnaz was all business until they retired to their homestead between seasons. When they were first married in 1940, Desi Arnaz had to give his wife-to-be a ring from a drugstore because all of the jewelry stores were closed. She wore it for the rest of their marriage. In 1960, Ball and Arnaz shocked fans when they divorced just two months after filming the final episode of The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour, though the two remained close friends until his death in 1986, even though both would go on to remarry. Both made it clear in multiple interviews that each was the love of the other’s life.

During the “Red Scare” of the mid-fifties, Lucille Ball’s career almost came to a halt when she was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, affirming she never had any intentions of voting as a member of the Communist Party. In the hearings she confessed to not knowing anything about politics. With her past dug into, it was verified that she registered as a Communist in 1936 to please her grandfather, Fred Hunt, who wanted all of his grandchildren to do so. Thankfully, Ball was cleared of all charges and suspicions.

Lucille Ball attempted to revive her television career — twice — with The Lucy Show (1962-1968) and Here’s Lucy (1968-1974). Neither program found the same success as I Love Lucy and after the latter program concluded, Lucille Ball was quoted as saying, “It was a hell of a jolt to find myself unemployed with nothing to do after more than 25 years of steady work.” She starred in a number of television specials, made numerous guest appearances on other programs and appeared on several awards shows. Her appearance at the 1989 Academy Awards, standing alongside her longtime close friend Bob Hope, resulted in a standing ovation. Her health, however, was taking a steep decline. Just a year prior she was admitted to Cedars-Sinai Hospital after suffering a stroke. Weeks after the Academy Awards ceremony, Ball was hospitalized after suffering from an aortal aneurysm. She underwent surgery and the following day her aorta ruptured. She passed away April 26, 1989.

Her success can be measured in many forms. In 1968, Lucille Ball was reported to be the richest woman in television, having earned an estimated $30 million. She remains the only Hollywood celebrity to grace the front of two postage stamps. A 34-cent stamp, issued in 2001 and a 44-cent stamp, issued in 2009.

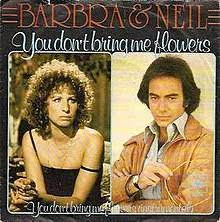

LEND ME YOUR EARS | THIS MONTH’S SONG: YOU DON’T BRING ME FLOWERS, Neil Diamond & Barbra Streisand

RELEASED: 1978

by Lisa Wolf

Click here to watch on YouTube.

“This song was actually written for a television show that was to be produced by Norman Lear, All That Glitters. The premise of the show was that the roles of men and women were juxtaposed: the men stayed home with the babies and did the housework, and the women went out to work” ~ Neil Diamond

“I ran into a problem with Norman who said, ‘I like the song a lot but I have to own the copyright if I’m to use it in my show’ and I said no. So I put it on my next album (1977’s I’m Glad You’re Here With Me Tonight) as a solo and Barbra really liked it and recorded it herself on her next album (Songbird), in the same key that I did and using the same arranger, so it was very similar. After both records were out, disc jockeys around the United States intercut the two records and made a duet out of them. Barbra and I somehow received some copies of these, and we looked at each other and a light bulb appeared in a bubble above our head and we said, ‘Hey, let’s go in and do it for real.’ It was an enormously successful record.”

At the 1980 Grammy Awards, Streisand and Diamond performed this song to close out the ceremony. It was nominated for Song Of The Year, but lost to “Just The Way You Are” by Billy Joel.

Click here to watch on YouTube.

Chicago WGN radio personality Roy Leonard and producer Peter Marino were big fans of Neil Diamond. When they heard Barbra Streisand’s version, they created a cutting room duet. Leonard put it on the air and the WGN phone lines went crazy. This turned out to be the recording world’s first ‘mash up’. Columbia Records brought Streisand and Diamond together for an official version. It was released in October of 1978 and went to #1 on the Hot 100 chart. Ironically, the idea began as a 45-second theme song for a failed TV show concept.

Chicago WGN radio personality Roy Leonard and producer Peter Marino were big fans of Neil Diamond. When they heard Barbra Streisand’s version, they created a cutting room duet. Leonard put it on the air and the WGN phone lines went crazy. This turned out to be the recording world’s first ‘mash up’. Columbia Records brought Streisand and Diamond together for an official version. It was released in October of 1978 and went to #1 on the Hot 100 chart. Ironically, the idea began as a 45-second theme song for a failed TV show concept.

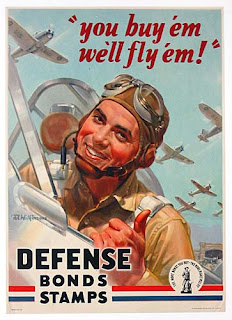

THE 1943 INFORMATION PLEASE WAR BOND TOUR

by Martin Grams

In November of 1942, it was publicly reported that Information, Please was going on tour for the War Savings Staff of the Treasury Department. Never seen outside New York except for the movie versions, the program visited cities along the eastern seaboard in an ambitious attempt by its creator and owner, Dan Golenpaul, to raise several million dollars for the war effort. The first stop was Symphony Hall, Boston, on December 4, 1942, where it was hoped that at least $1,500,000 would be realized.

The three regulars, Levant, Adams and Kieran, and their presiding officer Fadiman, participated on the tour, which for starters was limited to one out-of-town appearance a month. According to a press release, a visit to Philadelphia was scheduled in January of 1943 and, if all went well, future visits in Baltimore, Washington, Hartford and perhaps Rochester or Buffalo.

Dan Golenpaul, who was meeting the expenses of the tour, said that tickets would be priced from a $25 Bond for balcony seats to perhaps as high as $50,000 for an aisle chair in Row A. In Boston, the ticket distribution would be handled by the local War Savings Staff. The day before the Friday broadcast, Adams, Kieran and Levant were on hand for a little personal bond selling at strategic points in Boston.

Aside from the regular broadcast, bond buyers would see the usual “warm-up” period of questions before the formal program and, in addition, Adams and Kieran, who were considered “wonderful material for vaudeville” by Golenpaul, would do a little extra business. Levant also addressed himself at the piano. Golenpaul was not inclined to reveal the names of guest experts far enough in advance for local areas to advertise, pending their acceptance of invitations to participate.

Golenpaul’s initial intention of selling $1,500,000 worth in bonds was realized by their second visit. The January 9, 1943 issue of the New York Times reported: “Philadelphia, Jan. 8 – Thirty-four hundred persons who crowded the Academy of Music tonight to hear the Information, Please radio program, now on tour, bought a total of $6,314,123 in war savings bonds. The experts of the show were joined by Representative Will Rogers, Jr. of California, son of the humorist.” Evidently the war bond drive was extremely successful, and Golenpaul extended his tour along the East Coast for the rest of the 1943 calendar year.

For the broadcast of June 28, 1943, Chicago got its first look at Information, Please in action. The 3,500 or so people who filled all but a couple of the seats in the giant Civic Opera House enjoyed the radio experts’ performance to the maximum, and went home feeling that the price of admission—a war bond from $50 to $5,000 in denomination—had been well-spent in more ways than one. The total war bond “take” for this trip was $6,818,107.

For the broadcast of June 28, 1943, Chicago got its first look at Information, Please in action. The 3,500 or so people who filled all but a couple of the seats in the giant Civic Opera House enjoyed the radio experts’ performance to the maximum, and went home feeling that the price of admission—a war bond from $50 to $5,000 in denomination—had been well-spent in more ways than one. The total war bond “take” for this trip was $6,818,107.

Richard K. Bellamy, radio editor of the Milwaukee Journal, was in the audience to get a first look and report on the visual aspect – the part a radio audience could not get at home. “As a radio show this one is very smartly staged,” Bellamy wrote. “Even to the lone feminine aspect, a lovely, anonymous girl with a rose in her hair who sang several snatches to illustrate a song question on the broadcast. First Levant played some Gershwin on the piano with professional skill. Then Kieran arose, strapped on an accordion and slaughtered ‘I’m Just Wild About Harry’ (we think that’s what it was) as cruelly as any tavern player has ever slaughtered it. He grinned from ear to ear all the while, and the crowd loved him. Adams put a pencil in his teeth and knocked off an unidentified melody on that crude instrument with his fingers. Kieran and [Walter] Yust closed the performance with a piano duet, ‘Chopsticks.’ It’s amazing how little it takes to win over 3,500 people. At 9:15 Fadiman started asking some preliminary questions to get the board into the swing of things. He warned the audience: ‘You, the cream of Chicago, will know the answers before these lugs up here on the stage. But please don’t coach them.’ Even during the broadcast Fadiman seemed perfectly relaxed, always waiting, like a cat, for an opening. He seizes openings lightning fast and without any visible effort.”

In Chicago, Golenpaul played the role of director with perfection. He often sat with Fadiman, whispering occasional comments, and once or twice he crossed to the other table and nudged Yust a little closer to the microphone. He had decreed, “No photographers at the broadcast.” Apparently his rule was law because no pictures were taken.

“We did a lot of travelling with Information, Please,” recalled Oscar Levant, “and we were celebrities wherever we went. In Hartford, we dined at the governor’s mansion. Fadiman sometimes wrote the speeches with which the dignitaries welcomed us. In Cleveland, Senator Lausche – the alleged Democrat who was to the right of Goldwater – was the mayor and greeted us. In Toronto, Lester Pearson made a speech, presented us with gifts, and thousands of crack troops paraded in front of us in tribute. It was mighty flattering but I was embarrassed. I didn’t think we rated that.”

On September 27, 1943, Information, Please originated from the stage of the Mosque Theatre in Newark, New Jersey, with two very special guests: Vice President of the United States Henry A. Wallace and Representative James W. Fulbright of Arkansas. Exactly $277,398,975 in war bonds were sold that evening as a result. $275 million dollars of the total came from a group of local business concerns. V.P. Wallace said that the “common man” was buying 50 percent more bonds in 1943 compared to 1942.

“And he is going to do still better,” he added. “He must do better so as to put our armies into Berlin and Tokyo as soon as possible. He must be better if we are to have a stable peace without inflation.” Asked by reporters after the broadcast what he had meant by his reference to a “partial alliance,” Henry A. Wallace laughed and said, “You’ll have to figure that one out for yourself.” The Vice President, incidentally, was to have appeared as a guest on the quiz program, but he shuddered at the prospect and took no part in it other than to give a brief talk during the opening minutes. Representative Fulbright substituted for him in the question-and-answer period. Clifton Fadiman announced that the war bond total had been contributed by 3,277 people for the broadcast, all of whom bought bonds ranging from $50 to $5,000 to gain audience admission to the broadcast.

For more information about the book, visit www.MartinGrams.com

Hollywood 360 Schedule

3/4/23

Suspense 1/30/47 Three Blind Mice

Duffy’s Tavern 1/18/44 Archie Song w/ guest, Lauritz Melchoir

Barrie Craig, Confidential Investigator 3/9/55 Corpse on the Town

Rogue’s Gallery 2/21/46 The Alibi Murder

WhiteHall 1212 1/27/52 The Murder of Little Phillip Avery

3/11/23

The Abbott & Costello Show 3/17/49 St. Patrick’s Day Show

The Screen Guild Theater 3/17/47 The Philadelphia Story

Have Gun-Will Travel 7/5/59 Comanche

The Burns & Allen Show 3/10/42 The Fowlers won’t leave

Under Arrest 6/26/49 The Paris Road

3/18/23

Pat Novak, For Hire 2/27/49 The Marcia Halpern Case aka Don’t Tell Hilda

My Favorite Husband 10/7/49 George Tries for a Raise

X Minus One 8/1/57 End as a World

I Was a Communist for the FBI 12/29/52 Capitol City Square Dance

Crime Classics 12/2/53 If a Body Need a Body, Just Call Burke and Hare

3/25/23

The Bickersons 6/12/51 Mink Coat

Tales of the Texas Rangers 5/4/52 Little Sister

Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons 11/7/52 Murder and the Prize-Winning Bull

Dragnet 5/25/50 The Big Key

The Story of Dr. Kildare 5/31/50 The Abandoned Baby

© 2022 Hollywood 360 Newsletter. The articles in the Hollywood 360 Newsletter are copyrighted and held by their respective authors.