NEWSLETTER | VOL. 19, November 2022

Welcome to this month’s edition of The Hollywood 360 Newsletter, your place to get all the news on upcoming shows, schedule and interesting facts from your H360 team!

Carl’s Corner

by Carl Amari

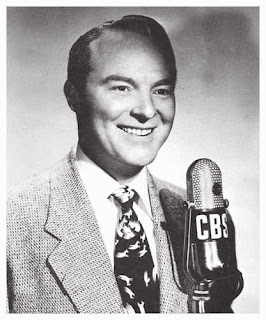

Hello everyone and Happy Fall! Here’s the Hollywood 360 newsletter, November 2022 / Vol. 19. As someone on our mailing list, you’ll receive the most current newsletter via email on the first day of every month. If you don’t receive it by the end of the first day of the month, check your spam folder as they often end up there. If it is not in your regular email box or in your spam folder, contact me at carlpamari@gmail.com and I’ll forward you a copy. The monthly Hollywood 360 newsletter contains articles from my team and the full month’s detailed schedule of classic radio shows that we will be airing on Hollywood 360. Each month I’ll provide an article on one of the classic radio shows we’ll present on Hollywood 360. This month, we’re airing a thrilling sci-fi story on Dimension X the week of November 12th, so here’s an article on this great series (photo is Norman Rose, host of Dimension X). Enjoy!v

CLASSIC ADVENTURES IN FUTURE TENSE

By Carl Amari and Martin Grams

Radio’s ‘Dimension X’ paved the way for TV’s science fictions shows

Airing on NBC in 1950 and 1951, Dimension X was one of the first seri ous science fiction anthologies on radio. Its high-quality dramatizations of gripping stories set the standard for future science fiction broadcasts on radio and television.

ous science fiction anthologies on radio. Its high-quality dramatizations of gripping stories set the standard for future science fiction broadcasts on radio and television.

Through its adaptation of published work from authors such as Isaac Asimov, Kurt Vonnegut, Robert A. Heinlein, Robert Block (best known as the writer of Psycho) and Ray Bradbury, Dimension X offered a serious take on science fiction. Time travel, space exploration, alien invasion and their (not always positive) consequences for the human race were common themes. The top-quality productions featured atmospheric sound effects and where broadcast from the studios of NBC in New York.

Before Dimension X premiered on NBC radio in 1950, the world of science fiction may have been, for many people, synonymous with the juvenile comic-book adventures of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers. However, under the production and direction of Van Woodward, Fred Weihe, and Edward King, and through an arrangement with Astounding Science Fiction magazine, Dimension X injected credibility into the genre and inspired a new generation of science fiction fanatics.

Dimension X was an in-house product of NBC and featured New York’s finest supporting actors including Arnold Moss, Santos Ortega, Joseph Julian, Ralph Bell, Mason Adams (he later played the managing editor Charlie Hume on Lou Grant), Raymond Edward Johnson and Wendell Holmes. The narrator was Norman Rose, who opened each show with: “Adventures in time and space … told in future tense… Dimension X!” Rose would later supply the voice of Juan Valdez, the fictional Colombian coffee farmer who appeared in television ads for the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Columbia.

Unable to sell the Dimension X to a sponsor (except for a brief spell under General Mills for 13 weeks), NBC decided to cancel the program. Today, fans of the genre regard Dimension X as inspiration, as well as instrumental in popularizing the work of its then youthful science fiction writers.

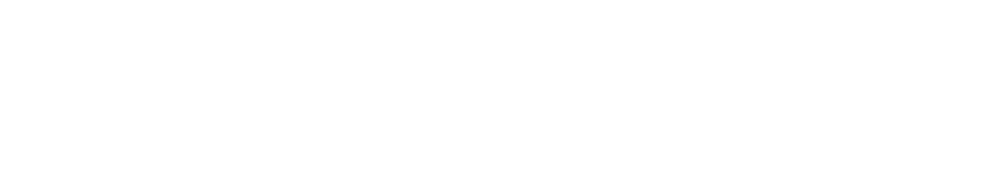

LEND ME YOUR EARS | THIS MONTH’S SONG: “Dueling Banjos” by Arthur “Guitar Boogie” Smith RELEASED: 1972 (for the film Deliverance)

by Lisa Wolf

Click here to watch on YouTube.

According to a 2014 obituary of Smith: The tune first reached a wide audience in 1963 when the Dillards bluegrass band played it with Andy Griffith on The Andy Griffith Show in the episode “Briscoe Declares for Aunt Bee.”

Dueling Banjos was written and recorded in 1955 as “Feuding Banjos” by Arthur “Guitar Boogie” Smith. A group called The Dillards popularized the song in the mid ’60s on the folk circuit, and it was their version that the author James Dickey heard and thought would fit nicely in the film version of his novel Deliverance. The song became famous when it was used in the 1973 movie in a scene where a city guy from Atlanta trades licks with a young simpleton in the backwoods. The film version was performed by Eric Weissberg on 5-string banjo and Steve Mandell on acoustic guitar. Weissberg and Mandell were folk musicians from New York City, but their musical inspiration was the Bluegrass sound of Appalachia.

Click here to view on YouTube.

Recorded for the film by Eric Weissberg and Steve Mandell, the song was released under the title “Dueling Banjos.” It went to No. 1 on Billboard’s adult contemporary chart, No. 2 on its all-genre Hot 100 chart and No. 5 on the country chart.

Unfortunately, the 1972 version of the song was used in the film without composer Arthur Smith’s permission — and credited to Weissberg as the composer — leading Arthur to successfully sue the filmmakers, ultimately receiving songwriting credit as well as royalties.

Dueling Banjos has been featured in TV commercials and covered by musicians of every instrument. Dueling Banjos has become Dueling Harmonicas, Dueling Accordions and Dueling Guitars. The “banjo battle” has become a prominent rite of passage for young musicians.

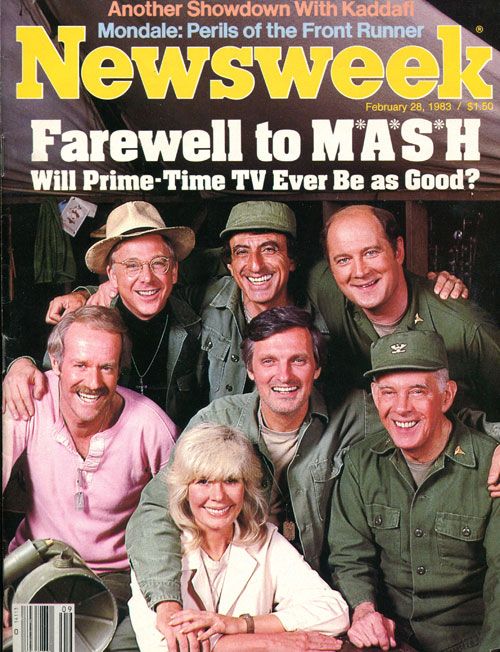

The 50th Anniversary of TV’s M*A*S*H

The 50th Anniversary of TV’s M*A*S*H

Part 2

by Barry Richert

By 1976, M*A*S*H had become appointment viewing. The program had won numerous accolades, including People’s Choice Awards, Emmys, Peabody Awards, Golden Globes, Writers Guild of America Awards, the Humanitas Prize, and many others. Larry Gelbart, who adapted the show for television and wrote most of the scripts for the first four seasons, had helped make the series an unprecedented success. After the fourth season, however, Gelbart decided to leave, believing that he’d done his best work and his writing had become repetitive.

“There is a genuine loss when a fine mind like Larry Gelbart’s departs,” asserted creator/writer Gene Reynolds in The Complete Book of M*A*S*H by Suzy Kalter. “He’s one of the finest comedy writers of our time. When he walked away after being so devoted, it was hard. Losing him was a blow, but I think we did very well. The writers rose to the occasion.”

Many believe that, whether intentionally or not, Year Five of M*A*S*H was a transitional season, leading into the more drama-centric Years Six through Eleven. Producer Burt Metcalfe had a similar take on the series’ season breakdown: “Some people say that Years One through Five are similar and that Six through Eleven are of a different ilk, and they tend to call those later shows more sentimental. Others, myself among them, see Years One through Four being similar, Year Five separate, and then Six through Eleven different yet again.”

Year Five proved to be another turning point for the series, due to two episodes: “Margaret’s Engagement,” in which Margaret returns from Tokyo with the news that she is engaged to Lieutenant Colonel Donald Penobscott, and “Margaret’s Marriage,” the title of which speaks for itself. After “Margaret’s Engagement,” the once rigidly military—and decidedly libidinous—partnership of Frank Burns and Margaret Houlihan was no more, a fact that had an indelible impact on the characters.

MALIBU, CA – JUNE 18, The last episode of MASH .Goodbye, Farewell and Amen Goodbye, Farewell and Amen remained the most watched television broadcast in American history, Loretta Swit, Mike Farrell, Alan Alda, Harry Morgan, Jamie Farr, Allan Arbus Fox Ranch, June 18, 1984 at the Malibu Creek State Park in California ( Photo by Paul Harris/Getty Images )

Actor Larry Linville believed that was the beginning of the end for Frank Burns: “When Frank and Hot Lips were no longer a duet, I think there were structural problems…I think Hot Lips and Frank’s relationship was pivotal to the show. Once it dissolved, there were a goodly number of problems. Loretta wanted her own identity separate from Frank Burns. I’m not sure, but I think that’s what was involved and why changes had to be invoked.”

Actor Larry Linville believed that was the beginning of the end for Frank Burns: “When Frank and Hot Lips were no longer a duet, I think there were structural problems…I think Hot Lips and Frank’s relationship was pivotal to the show. Once it dissolved, there were a goodly number of problems. Loretta wanted her own identity separate from Frank Burns. I’m not sure, but I think that’s what was involved and why changes had to be invoked.”

Linville decided it was time to leave: “My contract was up at the end of Year Five and I had the option to negotiate or take a walk. I felt I had done everything possible with the character, so I told them I was leaving. I’m not sorry I left…I was saturated with playing only Frank.”

Concurrent with Linville’s departure, there was once again a behind-the-scenes change brewing. Gene Reynolds decided to leave after a salary dispute with 20th Century Fox. “I remember Year Six vividly because it was the first year I produced M*A*S*H alone, and I was scared stiff,” Burt Metcalfe recalled. “The episodes are definitely different in Year Six. We didn’t want to try to imitate what had gone before. We couldn’t be the comic genius that Gelbart was. We had to find our own ground…Some people will say we got into sentimentality, but we had used many of our best guns comically.”

In the premiere of Year Six, Frank Burns’ disappearance is explained by way of his distress over Margaret’s marriage: convinced he’s found Margaret and her new husband, he is arrested for disturbing a brigadier general and his wife in a public bath in Tokyo. To fill the gap—and the bunk—left by Frank Burns’ departure, Dr. Charles Emerson Winchester III, played by David Ogden Stiers, is assigned to the 4077th. The imperious Winchester makes it clear he’s too good for “this hellhole,” immediately alienating Hawkeye and B.J. (who suggests, “Let’s avoid the rush and start hating him now.”). Winchester’s blustery arrogance was a stark contrast to the weaselly sniveling of Frank Burns, providing Hawkeye and B.J. with a more formidable tentmate to torment.

As the dust settled on the 4077’s various departures and arrivals, the series found a new groove, focusing on more character-driven stories. “The Winchester Tapes” in Year Six finds Charles recording a tape for his parents chronicling several incidents at the 4077, including Hawkeye and B.J.’s attempts to make him think he’s losing too much weight by swapping out his clothes. In “Comrade in Arms,” Hawkeye and Margaret are driving to another MASH unit when they get caught in military fire and their jeep stalls. Forced to spend the night in an abandoned hut, a barrage of shelling drives them into each other’s arms.

In Year Seven, “Point of View” was an innovative episode told through the eyes of a wounded soldier who is taken to the 4077 for treatment. That year saw several other developments, including the return of Colonel Flagg, a party held stateside by the families of the 4077, and, perhaps most poignantly, the divorce of Margaret from Lieutenant Colonel Donald Penobscott.

In Year Seven, “Point of View” was an innovative episode told through the eyes of a wounded soldier who is taken to the 4077 for treatment. That year saw several other developments, including the return of Colonel Flagg, a party held stateside by the families of the 4077, and, perhaps most poignantly, the divorce of Margaret from Lieutenant Colonel Donald Penobscott.

Year Eight is probably best remembered as the year Radar O’Reilly went home. Radar actor Gary Burghoff explained, “In the seventh year, I notified the producers that I would not be coming back. I felt the public deserved and would enjoy a conclusion to Radar’s involvement with the 4077, and I wanted to come back for a final show. The network disagreed at first. McLean Stevenson’s leaving had caused a big stir, so they didn’t want to make an issue of it…So I concluded the seventh year without a good-bye show. During hiatus, the network changed its mind and we negotiated for the two-parter that aired in Year Eight, ‘Good-bye Radar’.”

In the episode, Radar receives a wire from home reporting that his Uncle Ed has died. Colonel Potter recommends Radar go home on a hardship discharge since his mom wouldn’t be able to take care of the family farm alone. Radar is hesitant—he thinks he should stay, unconvinced that Klinger could ever learn the ropes of being company clerk. But Klinger proves himself capable by locating a much-needed generator for the camp, leading Radar to realize the 4077 can survive without him. His good-bye party is interrupted by an influx of wounded, so his final encounter with Hawkeye is an exchange of salutes through the window of the OR.

“Good-bye Radar” marked the last time a major character would depart the 4077. The show began what would turn out to be a four-year-long home stretch. In those final years, the 4077 battled Hemorrhagic Fever, Hawkeye wrote a letter to President Truman urging him to stop the war, Klinger saved Winchester’s life, Margaret was accused of being a Communist sympathizer, a nurse was killed by a mine after a date with Hawkeye, and Winchester saved the life of a soldier with a severe chest wound who needed an operation within 20 minutes or he’d be paralyzed (the episode was shown in real time with a clock in the corner of the screen).

In Year Eleven’s “As Time Goes By,” Margaret and Hawkeye clash on what items to include in a time capsule being buried at the 4077. The two ultimately find common ground in a collection of articles that represent the spirit of the camp, including a fishing fly made by Colonel Blake and Radar’s teddy bear. “As Time Goes By” was the last episode of M*A*S*H to be filmed, but it was not the last to air. That honor went to the two-and-a-half-hour series finale, “Goodbye, Farewell and Amen.”

“We knew M*A*S*H was coming to an end by Year Ten,” Burt Metcalfe maintained. “CBS kept asking us if we wanted to continue. Alan [Alda] pretty much spearheaded the situation. It was decided that Eleven would be the last year.” The series finale boasted a collection of eight writers, including Metcalfe and Alda. The episode’s plot features numerous storylines showing the effects of the ceasefire on the personnel of the 4077 and includes good-byes between characters that are equal parts hysterical and heartrending.

Directed by Alan Alda, the finale took 30 days to shoot between September and December of 1982. The long shoot was due to a fire that destroyed the M*A*S*H set that October, which made for a hectic schedule since the cast and crew were simultaneously filming the balance of the episodes for Year Eleven. Advertiser enthusiasm was so high for the finale that 30-second commercial blocks sold for more than some of the slots for that year’s Super Bowl.

“Goodbye, Farewell and Amen” aired on February 28, 1983, and was a massive television event. M*A*S*H watch-parties were held in homes all over the country, fans assembled in bars dressed in Army fatigues, and students in Alan Alda’s old Fordham University dorm even built a still and supplied libations during the episode. The finale ultimately attracted a total audience of 121.6 million viewers and made CBS $13.6 million. At this writing, it holds the record as the most-watched scripted episode of television in history. It capped off an eleven-year run that saw the series grow from a low-rated, small-screen reworking of a movie to a television institution with its own identity.

The last word on M*A*S*H must, of course, come from Larry Gelbart, whose memoir Laughing Matters includes the following observation: “It is estimated that the vast store of M*A*S*H episodes to be rerun in syndication will keep the series around well into the twenty-first century…Thinking of the possibility of M*A*S*H playing so far into the future leads me to hope, paraphrasing Winston Churchill, that if America and its television audience should last a thousand years, people will say this was their finest half hour.”

CLARA BOW ON TRUTH OR CONSEQUENCES

by Martin Grams

Hollywood celebrities participating on a radio quiz program was not uncommon during the forties. In 1946, when Jack Benny prompted an “I Can’t Stand Jack Benny because…” contest, inviting radio listeners to submit the closing half of the statement, screen horror icon Peter Lorre was one of the three judges. (Ronald Colman read the prize-winning submission.) But when it came to stunts, you could look no further than Ralph Edwards and his quiz show, Truth or Consequences, which is regarded as one of the most popular audience participation programs of the forties. Little did he know at the time the program first premiered in the airwaves, on the evening of August 17, 1940, he would ultimately become host to one of the most popular sex symbols of the silent cinema…. Clara Bow.

Sponsored by the Procter & Gamble Company, Truth or Consequences originated out of New York City with Ralph Edwards as master of ceremonies and Bill Meeder at the organ. Participants were picked from the audience and on mike was asked a question. If the contestant answered correctly, they received $15. If they answered incorrectly, they received $5 — but they must pay a consequence — which was usually submitted by the radio audience. The best consequence act of the evening, as shown by the applause meter, won a $25 Defense Bond. Contestants who were chosen from the audience but did not get a chance to appear on the program received $2. Each contestant, whether appearing on the program or not, received five large cakes of Ivory Soap. (Procter & Gamble had to inject their product placement somewhere…)

Highlights of the program included the April 5, 1941 broadcast, which originated from Hollywood instead of New York City. During the program, Mrs. James Hays, winner of the Grand Prize in the Ivory contest, spoke a few words. On the August 2, 1941 broadcast, Martin Lewis, editor of Movie-Radio Guide magazine, presented a trophy from the magazine to Ralph Edwards for his program.

Beginning with the March 17, 1945, broadcast, Truth or Consequences originated out of Hollywood instead of New York. The format of the program also changed with the times, offering unique ways of awarding prizes to contestants. On the evening of December 29, 1945, Edwards began what was intended as a spoof of giveaway shows but soon propelled into a phenomenon. Each week a veiled mystery man, known only as “Mr. Hush,” gave clues to his identity in doggerel. Edwards wanted Albert Einstein, who wasn’t interested: he settled for Jack Dempsey, which took five weeks for a contestant to guess correctly. The pot built week after week, providing the winner of that contest a total of $13,500.

A subsequent “Mrs. Hush” contest began on the evening of January 25, 1947. The stunt was tied in with the March of Dimes. Listeners who heard the woman’s voice and thought they could identify the owner of the voice could send their letters to “Mrs. Hush, Hollywood, California.” (Back then the U.S. Post Office was able to deliver letters with such addresses. And letters were delivered almost overnight. Talk about the inefficiency of today’s system!) Listeners were instructed to completed in 25 words of less the following sentence, “We should all support the March of Dimes because —–.” Radio listeners had to make sure their name, mailing address and telephone number were printed plainly in the upper right-hand corner of the paper upon which their letter was written. They were also required to include a contribution to the March of Dimes. Any amount was allowed. From a penny to a $100 bill, submissions and donations poured into the Mrs. Hush office. While the donations were accepted, an estimated ten percent of the submissions were thrown out people listeners did not write their name and phone number clear enough to be understood. (Hey, sloppy handwriting is more common than you think.)

A subsequent “Mrs. Hush” contest began on the evening of January 25, 1947. The stunt was tied in with the March of Dimes. Listeners who heard the woman’s voice and thought they could identify the owner of the voice could send their letters to “Mrs. Hush, Hollywood, California.” (Back then the U.S. Post Office was able to deliver letters with such addresses. And letters were delivered almost overnight. Talk about the inefficiency of today’s system!) Listeners were instructed to completed in 25 words of less the following sentence, “We should all support the March of Dimes because —–.” Radio listeners had to make sure their name, mailing address and telephone number were printed plainly in the upper right-hand corner of the paper upon which their letter was written. They were also required to include a contribution to the March of Dimes. Any amount was allowed. From a penny to a $100 bill, submissions and donations poured into the Mrs. Hush office. While the donations were accepted, an estimated ten percent of the submissions were thrown out people listeners did not write their name and phone number clear enough to be understood. (Hey, sloppy handwriting is more common than you think.)

The radio announcer explained that two weeks from tonight, the writers of the three best letters would have a chance to answer a telephone call from Ralph Edwards and have a chance to identify Mrs. Hush. The prize for identifying Mrs. Hush was a 1947 Ford Sportsman Convertible automobile, a Bendix washer, and a round-trip ticket to New York City for two with a weekend reservation at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel while in the city. Who could not resist mailing a donation to the March of Dimes for a chance at that?

For every week contestants could not identify Mrs. Hush, three more prizes were added to the pot. It was requested of the radio audience not to include the name of Mrs. Hush in their letters — that would be reserved for the phone call broadcast “live” on the air. Listeners could submit a donation every week if the contestants could not guess correctly.

Because the program was not transcribed and a repeat broadcast for the West Coast was “dramatized,” the West Coast radio audience was instructed to be at the phone during the East Coast broadcast, in case they were to receive the call. Only one attempt would be made to reach the listener. On a technical side, before the radio contestant went on the air, a representative of the radio program sought verbal permission to re-enact the on-air conversation for the West Coast broadcast.

The judges in the contest were Federal Judge J.F.T. O’Conner, Roy Natiger, head of the Los Angeles County Chapter of the National Foundation of the March of Dimes, and Dr. Vierling Kersey, Superintendant of Los Angeles City Schools. This was for the slogan contest and the choosing of the contestants. Entries were judged on the originality, aptness of thought, and sincerity. (And of course, whether the handwriting could be read.)

It was specified that Mrs. Hush could be from anywhere, and not necessarily from Hollywood. On the January 25, 1947, broadcast, Mrs. Hush read the following four-line jingle:

“Two o’clock and all is well;

Who it is I cannot tell;

Queen has her King, it’s true,

But not her ribbon tied in blue.”

A celebrity guest did assist with the January 25 broadcast, actress Louise Arthur, but she was not Mrs. Hush and that was clarified for the radio audience. For the February 1 broadcast, it was specified that any letters received through February 4 would be counted in the February 8 broadcast when Ralph Edwards phoned three lucky contestants. Letters received after February 4 and up through the next week would be used on the contest for February 15, etc.

Clara Bow during the silent era

Clara Bow during the silent era

On the February 1 broadcast, two of the famous Basenjis dogs, the barklessof Africa (Belgian Congo), were used in a contest. Ralph Edwards commented upon the growing popularity of the dogs as household pets in the country. He referred to the Magazine Digest January issue which had an article about the dogs. The dogs used on the program were flown in from the Hallwyre Kennels in Dallas, Texas. Three more prizes were added to the pot for this broadcast, even though Edwards did not call any contestants. A $1,000 full-length silver fox coat (provided by I.J. Fox), a Columbia Trailer, fully equipped and sleeps four, and a $1,000 diamond and ruby Bulova watch.

During the February 8, 1947 broadcast, the three people who were phoned had failed to identify Mrs. Hush, so three more prizes were added to the pot. These included a Tappan range, a Jacobs Home Freeze Unit packed with Birdseye Foods, and a 1947 RCA Phonograph-Victrola combination with 100 records. Edwards reminded the radio listeners that Mrs. Hush was heard from “Shang-ri-la,” an unknown place somewhere in the United States. The remainder of the program had a “reducing stunt” in which two contestants were presented with $15 each and a card entitling each to take a special reducing course of 12 lessons at Terry Hunt’s Health System on La Cienega in Hollywood. Also featured was a stunt titled “Baby Pig.” The pig was presented to a contestant, complete with nursing bottle, diaper, etc. so the contestant could care for it properly.

The February 15, 1947 broadcast originated from the Golden Gate Theater in San Francisco. The voice of “Mrs. Hush” remained unidentified and once again three more prizes were added to the pot to hold over for the next week. These included an electric refrigerator, a vacuum cleaner with accessories, and a week’s vacation for two in Sun Valley with air transportation both ways.

The program resumed in Hollywood with the February 22, 1947 broadcast. “Mrs. Hush” was again unidentified and three additional prizes were added: a Brunswick billiard table installed in the winner’s home and complete with all sporting accessories needed to play the game; a $1,000 art-carved diamond ring designed by J.R. Wood; and a complete Hart Schaffner Marx wardrobe of clothes for each adult man and woman in the winner’s family. There was a guest during the broadcast, Miss Clair Dodson, an Earl Carroll show girl, who assisted Ralph Edwards by entertaining one of the contestants.

The March 1, 1947 broadcast featured a stunt whereby guest Dick Moorman, a veteran now working and trying to find a place to live in California, dictates a letter to his fiancee back in Long Island, New York… or so he thinks as he dictates that he will send for her so they may be married as soon as he rents an apartment or a house for them to live. Actually, the fiancee, Miss Gloria Minay, was the girl to whom he was giving the dictation. She was aptly disguised by Hollywood makeup artists who made her hair blond and used blue contact lenses to make her brown eyes appear blue. Gloria and her family were flown to Los Angeles and all expenses were paid by the producers of the program. In addition, the couple after their Hollywood marriage would be sent to Chicago where they would enjoy an all-expense-paid honeymoon in a Celotex pre-engineered home built by the Celotex people on Seventh Street next to the Stevens Hotel in Chicago. The trip to Chicago and back would be made on the Superchief and when the couple returned from their honeymoon, they would find a Celotex house waiting to be put up for them wherever they wanted to live — the house would be just like the one in which they spent their honeymoon. Ralph Edwards told the audience that the house would be furnished with furniture as well. (When the contestant discovered that his fiancee was right on the stage with him, he said, “Oh, Christ!” which did not go over well with the network censors.)

The “Mrs. Hush” voice is once again unidentified and three more gifts were added for next week’s program: an Oil-O-Matic burner completely installed with a year’s supply of fuel, a Piper Cub airplane, and free maid service for one year. Due to a faulty line connection, at 8:54 p.m., the “Mrs. Hush” portion stopped momentarily and the two words, “has her,” was lost over the air.

During the March 8, 1947 broadcast, “Mrs. Hush” was once again unidentified. Three additional prizes were added to the pot: a 144-piece china set, a typewriter, and a complete house-painting job inside and outside with Sherwin Williams paint.

Finally, on the broadcast of March 15, “Mrs. Hush” was identified. Mrs. William H. McCormick of Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, answered her telephone call from Ralph Edwards and she said “Clara Bow.” Mrs. McCormick’s winnings, valued at the time between $17,590 and $18,000, included: a 1947 convertible car, an electric washer, round-trip plane ticket for two to New York City with a week and a suite at the Waldorf-Astoria, a $1,000 full-length Silver Fox fur coat, a house-trailer fully equipped for four people, a $1,000 diamond and ruby wrist watch, a home-freeze-unit stocked with frozen foods, a Tappan gas range, a 1947 RCA Victor console radio-phonograph with 100 records, a refrigerator (Electrolux), a full-size home-billiard table with all equipment and installation, a furnace with a year’s fuel supply to complete the home-heating unit; a 144-piece china set, free maid service for one year, complete house-painting job inside and out with Sherwin Williams paint, a typewriter, an all-Metal airplane, a week’s vacation for two at Sun Valley, Idaho, with transportation both ways, a $1,000 diamond ring, an electric vacuum cleaner with all the attachments and a complete Schaffner Hart Marx wardrobe for every adult member of the immediate family.

Mrs. McCormick said she planned to divide her winnings with her neighbor, Mrs. A.H. Timms, and her sister, Mrs. William Harmon, both of whom helped identify Mrs. Hush. Following the identification, there was a pick-up from Las Vegas, Nevada, for the special guests: Clara Bow (Mrs. Rex Bell), who told about the way she was heard as Mrs. Hush every week, broadcasting from an auto park near her Las Vegas home. With Clara Bow, appearing on the program, was her husband Rex Bell, and her two children, George and Toni Bell, who never knew their mother was Mrs. Hush until this very evening. Clara Bow then told how she kept her identity known from her family, including the nearest neighbor who almost surprised her just when she was starting out to the “Shang-ri-La” where she made her broadcasts. Ralph Edwards told Clara Bow that he was sending her a special award, as a way of saying “thank you.” A golden statuette, in behalf of the National Foundation of Infantile Paralysis, was going to be bestowed to Clara Bow as a result of the letters and contributions to the March of Dimes from contestants and radio listeners who sought to identify “Mrs. Hush.” An estimated total of $400,000 was raised as a result of the contest. According to a representative of the March of Dimes, this was the largest single radio contribution ever received by the March of Dimes Fund. More than one million letters were sent in by contestants, each with a donation.

During the broadcast of March 22, the guests were Mrs. William McCormick and her husband. Having won the Mrs. Hush contest the week prior, she and her husband were flown to Hollywood for the broadcast. They talked about what they planned to do with the prizes. The McCormick family included three sons (the oldest was 14 and the baby was 18 months). The boys were back home listening to the broadcast. The evening’s program featured a take-off called “Mrs. Hush’s Mother-In-Law” in which the mothers-in-law of three contestants were hidden in the studio. Each told their in-laws what they thought of them but the in-laws had to identify their respective mother-in-laws. Another stunt featured a girl sent to the corner of Sunset and Vine to organize a Community Sing. She received one dollar for every person who joined her singing group. The program had a pick-up from the corner so listeners could judge the success of the singing group.

Later in the year, starting October 4, Truth or Consequences stopped re-enacting the repeat broadcasts and instead recorded each episode for later playback. This system was dropped in August of 1948 and then reinstated in August of 1949. The program made a quick jump to CBS under sponsorship of Pilip Morris, before returning to NBC for Pet Milk. The radio program expired in 1956.

The “Mrs. Hush” contest also served as a clever marketing ploy to promote the radio program. Numerous periodicals covered the contest, hoping to convince their readers to tune in and try to guess the identity of the mystery woman. Perhaps no other contest on Truth or Consequences gained such momentum until 1948, when the secret identity craze peaked with the “Walking Man” contest, which built to a then-fabulous jackpot of $22,500. That’s right, folks had to guess who the mysterious man was simply by the way he walked. That man turned out to be Jack Benny.

Recorded for the film by Eric Weissberg and Steve Mandell, the song was released under the title “Dueling Banjos.” It went to No. 1 on Billboard’s adult contemporary chart, No. 2 on its all-genre Hot 100 chart and No. 5 on the country chart.

Unfortunately, the 1972 version of the song was used in the film without composer Arthur Smith’s permission — and credited to Weissberg as the composer — leading Arthur to successfully sue the filmmakers, ultimately receiving songwriting credit as well as royalties.

Dueling Banjos has been featured in TV commercials and covered by musicians of every instrument. Dueling Banjos has become Dueling Harmonicas, Dueling Accordions and Dueling Guitars. The “banjo battle” has become a prominent rite of passage for young musicians.

KILLER, COME BACK TO ME!: Ray Bradbury’s Entry Into Network Radio

by Karl Schadow

One of the most esteemed fiction writers of the 20th-Century, Ray Bradbury was best known for his accomplishments in the fantasy genre, most notably The Martian Chronicles. (Bradbury stressed that this subject was indeed fantasy and not science fiction.) This volume published in 1950 had many of its individual chapters transformed for radio performed on Dimension X, Escape and X Minus One. Despite the popularity of these ventures, none was the first network radio performance of a Bradbury tale.

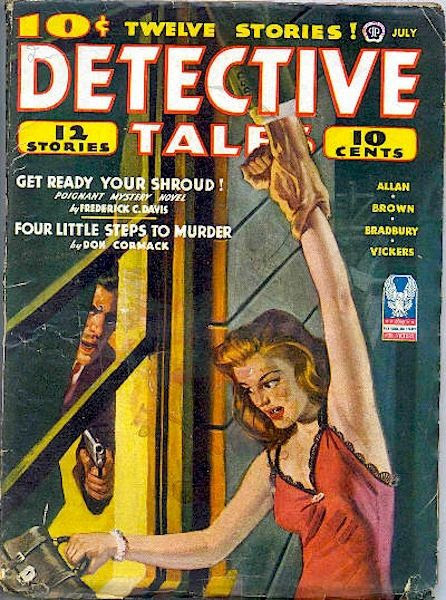

He had also crafted numerous crime and horror stories during his career which were published in various pulp magazines including Weird Tales, Dime Mystery Magazine and Detective Tales. In the July 1944 issue of this latter periodical, “Killer, Come Back to Me!” was the highlight. Its adaptation performed on The Mollé Mystery Theatre, May 17, 1946 was the coast-to-coast radio audience’s introduction to Bradbury’s work.

Detective Tales July 1944

Originating from New York, the weekly, half-hour series had been on NBC since September of 1943 sponsored by Sterling Drug, Inc. which promoted various Mollé brand products. Frank Telford of the Young & Rubicam advertising agency was the show’s producer/director and who selected “the best in mystery fiction” to be presented each Friday evening. Stories were culled from a wide range of authors including Anna Catharine Green and Cornell Woolrich, among many others. The yarns were narrated by the equally factitious Geoffrey Barnes, (portrayed by Bernard Lenrow). Though Bradbury was the original author of “Killer, Come Back to Me,” he did not write the radio script. The etherwaves version was penned by Joseph Ruscoll. His previous successes as an airwaves scribe included original stories on The Columbia Workshop and adaptations for The Cavalcade of America. Noteworthy is that Ruscoll’s most famous creation, “The Creeper,” had made its debut on The Mollé Mystery Theatre, March 29, 1946.

As with all radio adaptations of previous published works, there was some liberty taken with the plot and characters. However, Ruscoll captured the hard-boiled theme of the weak, wannabe gunman Johnny Broghman, who comes under the influence of the scheming gun-moll, Julie Barnes. Richard Widmark co-starred as the novice hoodlum with Alice Reinheart as the femme fatale. Both the pulp and radio stories commence with Julie forcing her participation into Johnny’s solo bank heist as the getaway driver. They both escape the scene but Johnny had been shot in the leg during the holdup. Interestingly in the pulp version his treatment of the injury is never explained while in the radio iteration, a doctor (portrayed by Don Douglas) is summoned to remove the bullet, without anesthesia, as Julie insists that Johnny needs to endure some pain to toughen his physique. Julie was the lover of a former gangster, Ricky Wolfe, whose death known only to her, occurred during a previous gunbattle. She wishes to groom her new student in crime to fill this romantic void and instructs Johnny on how to perfect his nefarious techniques. This also includes moving Johnny into Ricky’s former gang as its new leader, as the resemblance between the two is quite remarkable.

Ray Bradbury

However, once Julie and Johnny reconvene with the gang in Los Angeles, not all of its members are convinced by the impersonation and Johnny, to prove himself to the others, shoots and kills the gang’s top henchman, Merritt. In both the pulp and radio rendition’s this is a fairly gruesome scene. Johnny throws away the Ricky disguise and exerts his authority on the rest of the group using his real identity.

Unfortunately for Johnny, Julie has never accepted Ricky’s death and the relationship between the two sours quickly. Moreover, Julie does not want Johnny to collaborate with a gang led by Nick Vanning whose secretary, Franny, had been Julie’s previous rival for Ricky. This particular character (also played by Alice Reinheart) was introduced specifically in the radio script as another female voice andcompetition for Julie.

As in all radio shows, the crooks must meet their ultimate demise in the end. Julie’s dispatch is enacted in the same manner in both the radio and pulp stories, but Johnny’s brutal slaying is delivered by differing factions. Moreover, the pulp yarn has an additional shocker denouement. Readers are encouraged to seek out both accounts to learn their respective conclusions. The audio is readily available online and the pulp story has been recently reprinted in a 2020 compendium of Bradbury crime stories appropriately titled, Killer, Come Back to Me published in honor of the Centenary of the author’s birth.

In addition to his achievements in fantasy, Ray Bradbury should also be remembered for his excellent endeavors in crime fiction. Those having an interest in these activities may email this author at khschadow@gmail.com

Hollywood 360 Schedule

11/5/22

Arch Oboler’s Plays 3/9/40 Johnny Got His Gun

You Bet Your Life 2/7/55 Secret Word: Shoe

The Kraft Music Hall 10/7/48 w/ guest, Edward G. Robinson

The Adv. of Sam Spade, Detective 7/25/48 The Mad Scientist

WhiteHall 1212 4/27/52 The Case of Francesca Nichelson

11/12/22

Boston Blackie 5/28/47 The Ghost of Florence Newton

The Life of Riley 11/22/47 Win a Buick Contest

Frontier Town 10/31/52 Emily Bracket

Dimension X 4/29/50 No Contact

Big Town 12/28/48 Dangerous Resolution

11/19/22 (repeat of 11/20/21 show)

Night Beat 5/29/50 Harlan Matthews Stamp Dealer

The Jack Benny Program 11/30/47 The Turkey Dream

The Big Story 1/11/50 Gambling, Divorce and Murder

The Burns & Allen Show 3/6/47 Detective Gracie

Dangerous Assignment 7/23/49 Nigeria

11/26/22

Bold Venture 10/21/51 The Quan Yen Statue

The Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis Show 5/5/53 w/ guest, Anne Baxter

Suspense 10/21/48 Give Me Liberty

Frontier Gentleman 6/8/58 Sheriff Belljoy’s Prisoner

Cloak & Dagger 7/23/50 The Secret Box

© 2022 Hollywood 360 Newsletter. The articles in the Hollywood 360 Newsletter are copyrighted and held by their respective authors.